1844 And All That

Gideon Haigh on the origins of international cricket

The T20 World Cup begins this weekend with the USA taking on Canada in Dallas. USA will be favourites, reinforced as they are by West Indian Aaron Jones, New Zealander Corey Anderson and Rajasthan Royal Harmeet Singh; they recently whitewashed Canada in a five-match T20 rubber. But get ready to hear one factoid a lot - that the two countries have the longest-running international sporting rivalry, having met on the cricket field a hundred and eighty years ago, long before not only the inaugural Test match but the Americas Cup.

Yes, it falls into the ‘just fancy that’ category, but in many ways makes complete sense. No other countries in which cricket was played in those days had a common border - a border just stabilised by the Webster-Ashburton Treaty. The US had achieved a national identity by the war of independence, Canada by the Act of Union. They did not as yet have extensive trade ties - Canada, thanks to imperial preferences, was economically in Britain’s thrall. But they did have the rudiments of cross-border travel by ferry and stagecoach, which by the 1840s had reduced journey times from weeks to days. International sport correlates closely with reliable transportation - Anglo-Australian cricket would only prove thinkable once steam regularised the route between the hemispheres.

References to cricket in the US go back to the early 1700s, with New York, along with Philadelphia and Boston, among the early centres. Cricket even gets a mention at the outset of the republic. In 1789, during discussion of the proper title for the chief executive of the new United States, George Washington, John Adams objected to ‘president’ on grounds it was insufficiently grand. In For Fear of an Elective King (2014), Kathleen Bartoloni-Tuazon explains: 'As for the simple appellation of “President,” it was far too conventional and prosaic since “there were Presidents of Fire Companies & of a Cricket Club.”Adams conceived of “Highness,” “Most Benign Highness,” and “Majesty” as a part of the landscape of governance in America and the world and necessary to vigorous executive authority.' Others, presumably, thought that if 'president' was good enough for a cricket club, it was good enough for a republic, so president Washington he became.

The organisers of that first international encounter were leading clubs in both countries. Toronto CC had been founded as York CC in 1827; St George’s CC had been founded as New York CC in 1838. Had they not changed their names between times, their first skirmish would therefore have been, confusingly, York v New York. Fortunately, by 1844, the town of York had adopted the Inuit name Toronto, while the cricketers of New York had decided to proclaim the exclusivity of their membership restriction to British subjects by patriotically adopting the name of Britain’s patron saint. In other words, then, as now, cricket in the US was a diaspora game, except that expat Poms have since been succeeded by expat South Asians.

In his thoroughly useful book Real International Cricket (2016), Roy Morgan provides a detailed account of the early contacts between Toronto CC and St George’s CC. The virile Britishers of St George’s first travelled north in August 1840 in response to a bait dangled by a ‘Mr Philpotts’ purporting to act on behalf of Toronto. Only, on arrival, they found that this personage did not exist; they had been the victims of a con. As Morgan observes, it is a strange deception, in the absence of any financial incentive - more in the nature of a prank. ‘Was this someone who had a grudge against St George’s CC, perhaps a person who had been refused membership?’ Morgan speculates. ‘Was this someone obtaining revenge for a dispute with Toronto CC?’ We’ll never know, for whoever it was melted away, more successfully than the perfidious W. E. B. Gurnett who did the dirty on our pioneering indigenous cricketers in 1868.

Toronto and St George’s did agree to play a friendly, on 4 September, at the Caer Howell country club, won by the visitors, and sufficient goodwill developed for a reciprocal game to be entertained, only for the plans to fall through. When the New Yorkers themselves came back, Toronto protested that St George’s had brought three ringers from the Union Club of Philadelphia. Neither side would budge. St George’s president Thomas Green, obviously uneasy about the whole thing, resigned in embarrassment.

In the meantime, however, the Canadians had invited themselves to the US, offering a four-figure stake. Some at St George’s appear to have leery of another ‘Philpotts’ episode, but a majority accepted the challenge.

Toronto’s XI dutifully materialised at St George’s home ground on Bloomingdale’s Road on 24 September 1844 for ‘one of the greatest games ever played in this country.’

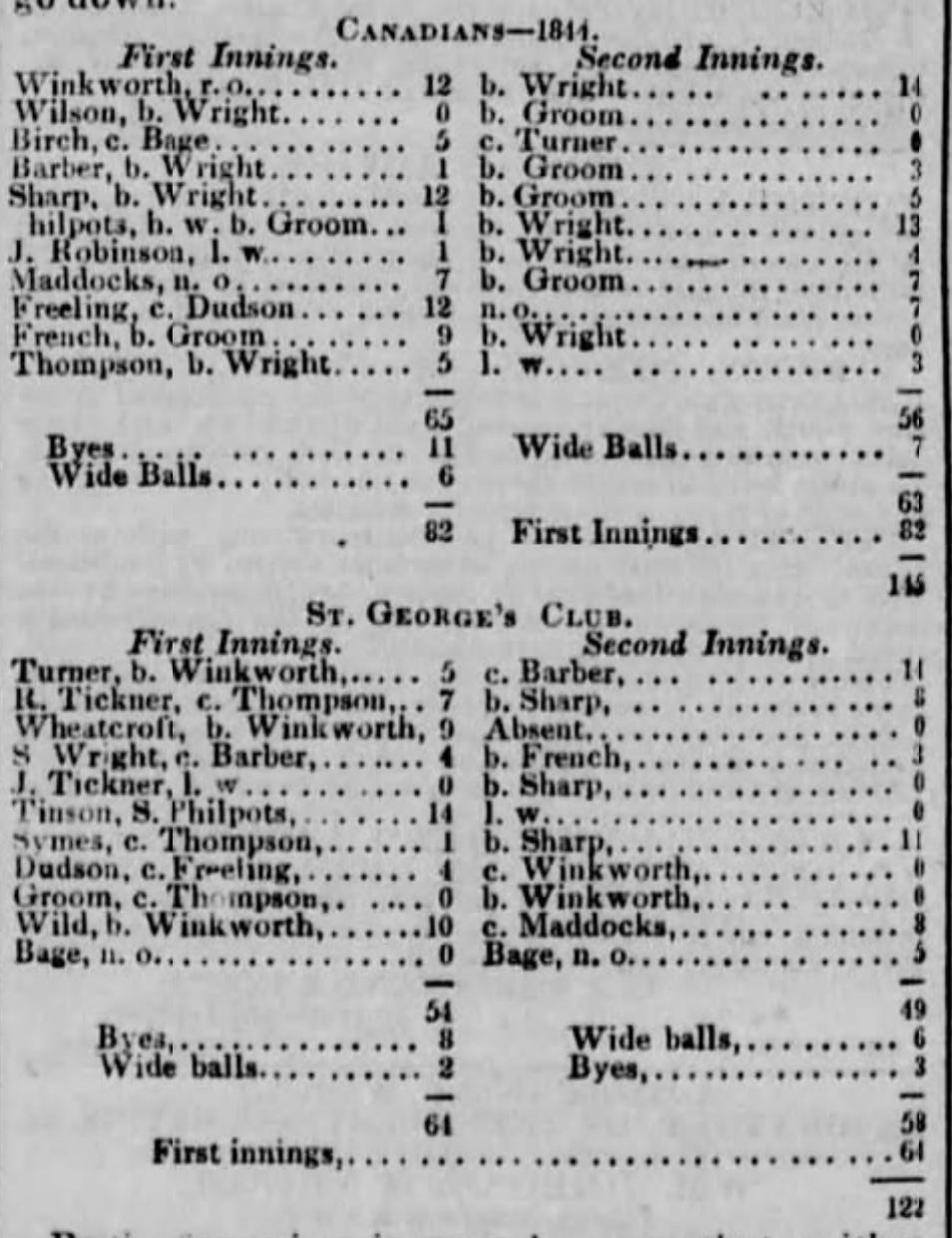

Actually, played over two days separated by a day’s rain, the cricket was undistinguished and rudimentary: underarm bowling, no boundaries, low scores. An umpire was replaced. One American player failed to turn up on time on the second day. But it was, interestingly, eleven-a-side - more than can be said for the first encounters between English and Australian cricketers seventeen years later. And parity in numbers is integral to a level playing field in all sport.

So, of course, is the idea of selection from a wider group, and this is, perhaps, why the 1844 game has come to be deemed more international than the 1840 game. The latter was clearly an encounter between clubs; in 1844, the visiting team was composed of seven players from Toronto, two from the Guelph Club, one from Kingston and one from Montreal. In reporting their victory by 23 runs, the New York Daily Herald felt entitled to call them ‘Canadians’, if not ‘Canada.’

Confusingly, the Herald did not confer on St George’s the honour of being referred to as the ‘USA’, despite the presence of players from the Philadelphia CC and the Union CC in Camden, New Jersey. But perhaps that reflected annoyance at St George’s membership restriction - a team of Anglos could hardly pass for Americans.

Still, Anglo-to-American conversion was possible. In 1844, another New York newspaper, Brooklyn’s Long Island Star, employed an Exeter-born teenage reporter called Henry Chadwick as, among other things, a cricket writer. He loved the game, played it enthusiastically, and continued to report on it for the New York Times. Then, in a fabled moment, in 1856, he chanced on a game of baseball on Elysian Fields in Brooklyn between New York’s Eagles and Gotham, and was captivated. Previously he had looked down on the local ball game as rough and trivial. Now he saw the future: ‘Americans do not care to dawdle over a sleep-inspiring game, all through the heat of a June or July day. What they do they want to do in a hurry. In baseball all is lightning; every action is as swift as a seabird’s flight.’

Chadwick became convinced that baseball was ‘suited to the American temperament’, and for his decades of tireless administrative and journalistic evangelism he is today known as ‘the Father of Baseball’. American cricket, in the meantime, contracted to a few centres, and never threatened baseball’s growing dominion. One wonders, of course, what Chadwick would make of T20, anything but ‘sleep-inspiring.’ We shall see what Americans make of it in the next month.