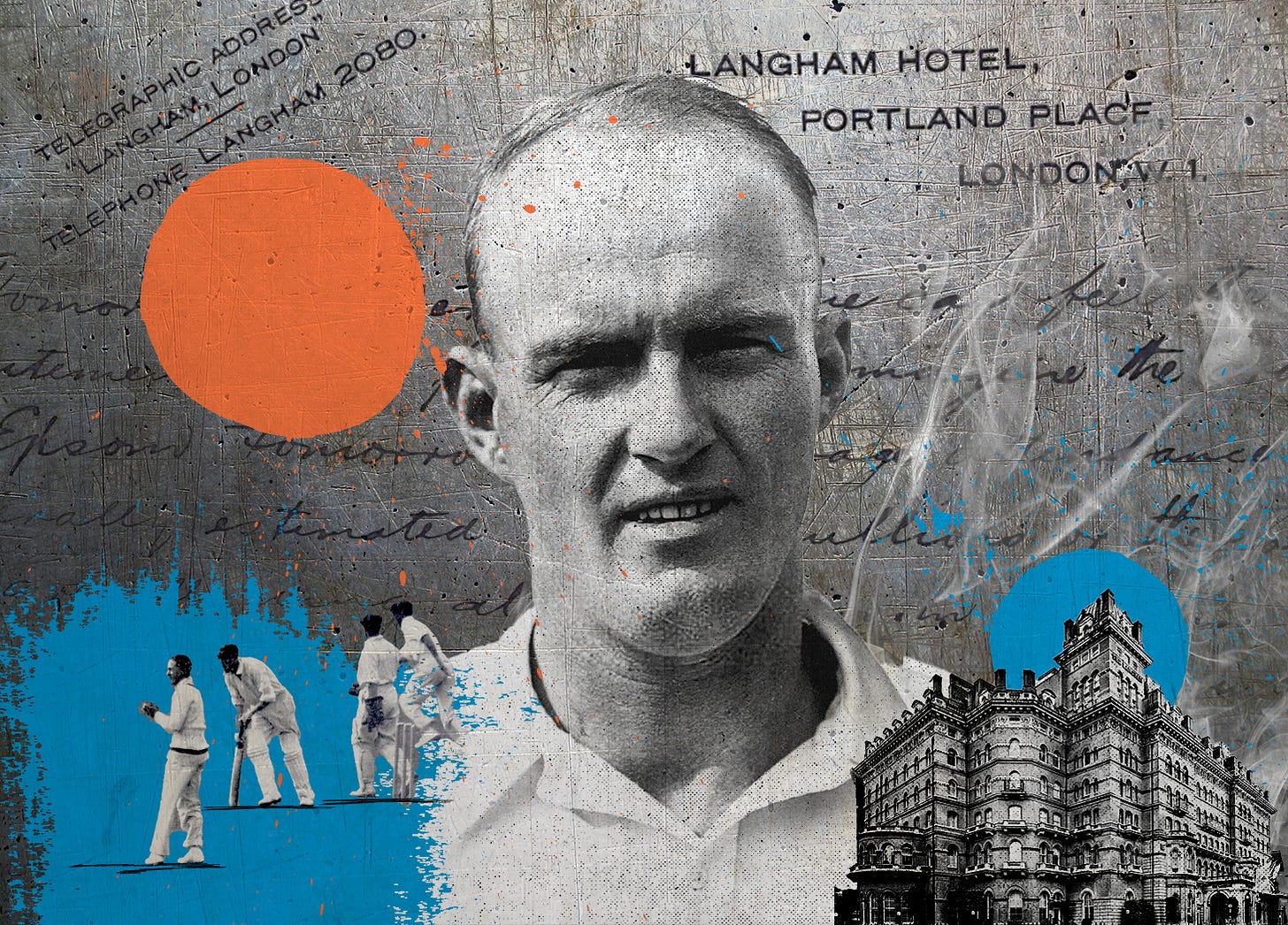

A LETTER FROM TIGER

Gideon Haigh on a word from 1934

Bill O’Reilly was a great leg-break bowler. Bill O’Reilly was also, for much of his cricket career, a schoolmaster. He undertook his first Ashes tour, 1934, on unpaid leave from the Education Department. But he did not forget his colleagues at Kogarah Intermediate High School, and provided the principal, Edwin Charles Arnold, with comprehensive periodic updates of his travels.

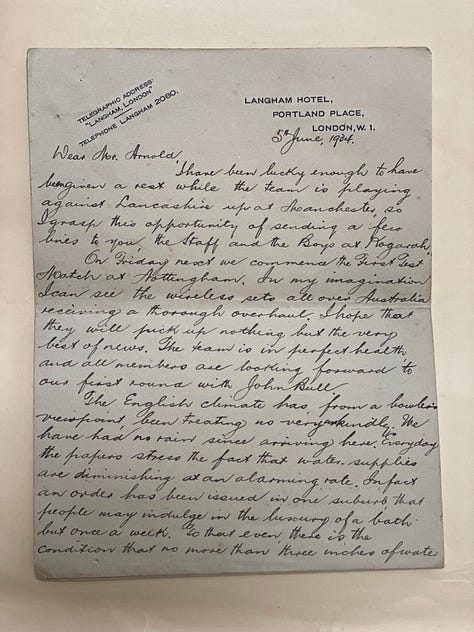

This six-page letter, preserved these many years by Arnold’s grandson Bill, has been kindly sent me by Arnold’s great granddaughter Maria, and I’m republishing it here on the 90th anniversary of its composition at London’s Langham Hotel, up top of Regent’s Street. It was posted just before the first of the five Tests. ‘In my imagination,’ says Bill, ‘I can see the wireless sets all over Australia receiving a thorough overhaul. I hope that they will pick up nothing but the very best of news.’ In the event, O’Reilly and his compadre Clarrie Grimmett took fifty—three of seventy-one English wickets to fall - a series-winning performance.

There is in the letter, however, comparatively little cricket, save the observation that pitches, thanks to hot weather, are as ‘hard as iron and dead as Julius Caesar’, and that ‘Clarrie Grimmett and I are thinking seriously about purchasing a watering can.’ The content is almost exclusively about places of historic interest - and O’Reilly was, after all, employed at Kogarah to teach history, English, geography and business principles. So comprehensive would have been O’Reilly’s education in the imperial story that the tour would have felt like visiting scenes of his own imagination.

The encounter with the British prime minister Ramsay MacDonald at Chequers, which took place on 18 June, is further elaborated in O’Reilly’s memoir Tiger:

Firstly I came to the rescue on Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald in supplying the dates of the reign of King Stephen, when our host had some difficulty estimating the age of a magnificent oak tree at his back door. Grateful, I suppose, for my timely assistance, MacDonald, resplendent in his Savile Row suit and his profuse mop of blue-grey hair, gave me a personally conducted tour of the historic mementoes entrusted to Chequers.

One of the items Macdonald showed O’Reilly was Oliver Cromwell’s famous 1644 letter to Colonel Valentine Walton after the Battle of Marston Moor, with its euphoric account of the slaughter of the Royalist cavalry:

Truly England and the Church of God hath had a great favour from the Lord, in this great Victory given unto us, such as the like never was since this War began. It had all the evidences of an absolute Victory obtained by the Lord's blessing upon the Godly Party principally. We never charged but we routed the enemy. The Left Wing, which I commanded, being our own horse, saving a few Scots in our rear, beat all the Prince's horse. God made them as stubble to our swords.

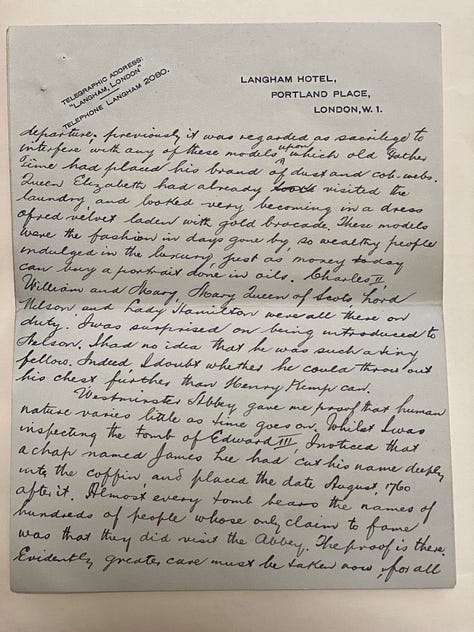

O’Reilly notes that ‘all second year boys’ will be familiar with the lines from their copies of the standard history text, Warner and Martin’s Groundwork - a book as legendarily dull as its name. But it’s since been interpreted more bloodily, and the tone attests O’Reilly’s Irish leeriness of Cromwell. What strikes O’Reilly most forcefully about Westminster Abbey, meanwhile, are its score of wax effigies. English history suddenly seems smaller than life: ’I was surprised on being introduced to Nelson. I had no idea he was such a tiny fellow.’ Livelier too: ‘Almost every tomb bears the names of hundreds of people whose only claim to fame is that they did visit the abbey.’

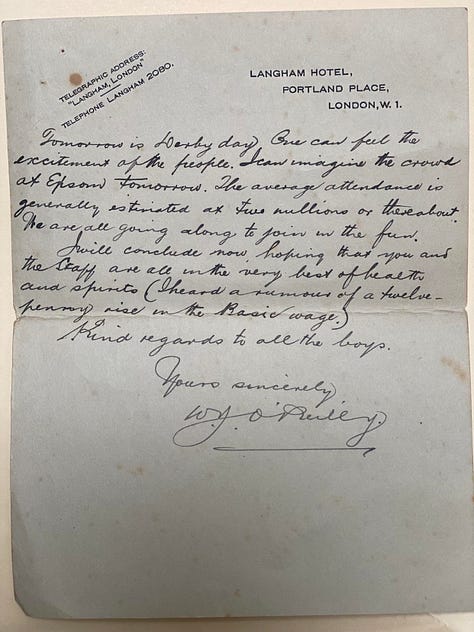

Still, to peruse the letter is to be reminded of the circles in which Australian teams once moved in England. Lord Hailsham, secretary of war, was also president of Marylebone. Lord Cromer was Lord Chamberlain. Sir James Barrie, creator of Peter Pan, had his own famous cricket club, the Allahakberries (allegedly Moorish for ‘God help us’). Also mentioned on page 5 are the Earl of Lonsdale (‘a grand old chap who has mutton chop whiskers and smokes cigars a foot long’) still infamous for his affair with the actress Violet Cameron, and JH Thomas [‘very humorous’], reputedly responsible for telling King George V a dirty joke so funny that his highness burst his post operative stitches.

O’Reilly notes that he expects to meet George V and the Prince of Wales during the Lord’s Test. It was six months since the latter had first bedded his mistress Wallis Simpson; the resulting crisis two years hence would draw in another of O’Reilly’s tour acquaintances, the Archbishop of Canterbury, who would accuse the prince of ‘a craving for private happiness’ that he had sought ‘in a manner inconsistent with the Christian principles of marriage.’ It’s all very….English. O’Reilly might have been a proud Irishman, but his fidelity to British institutions and inspirations is here hard to doubt. Likewise his regard for the language. The sentences are economical, and the handwriting immaculate - habits that O’Reilly maintained into his post-teaching career as a journalist. Viz Geoff Lawson’s account of writing to O’Reilly to complain of something the great man had written in the Sydney Morning Herald, only to have the missive returned promptly.

I opened the envelope to a red blaze across my original. As I panned down the page I found scant notes in red pen and none to do with cricket. Parallel lines, backslashes through words, indentation marks, squiggle red lines under sentences with ‘no predicate’, apostrophes annotated, capitals overwritten…At the bottom of the page was the only sign of continuous diction: ‘More attention to detail required, try harder next time 5/10.’

‘O’Reilly probably caused more trepidation among English batsmen than even Grimmett,’ wrote Wisden at the end of that tour in naming Bill one of the Five Cricketers of the Year. Just imagine the trepidation he caused his students.

I recall writing to The Cricketer many years ago about Barrie’s “Allahakberries”. It’s a play on the Arabic “Allahu Akbar” - God is the greatest - and, presumably, Barrie’s name.

What a treat. A delight to read the letter. Thanks Sent it off to my 89 year old Dad immediately. He has vivid memories of listening to The Invincibles Tour in 48 on the radio and as an Australian Irish Catholic, has laughed more than once at the imagery of Tiger and Fingo laughing their heads off when The Don got the famous blob.

I visited the Bradman museum in Bowral again recently for the umpteenth time and hadn’t seen the commissioned portrait of Tiger. His hands are enormous! What an outright assault facing him must have been!