A Night in Albury

GH at the last Winter Solstice

In 2011, Mary Baker, a talented and sensitive fifteen-year-old from Albury, took her own life after a long ordeal with an eating disorder. In Mary’s memory, her parents Annette and Stuart established Survivors of Suicide and Friends, which for the last thirteen years has staged an ever-growing evening event on the Winter Solstice featuring speakers describing their experiences of loss and sorrow.

It is a most remarkable happening - an authentic, organic community gathering drawing people from all over Australia in a forum of mass remembrance and mutual support. Guests have ranged from Kerry O’Brien and Patrick McGorry to Lauren Jackson and Rosie Batty. If you’ve twenty minutes or so, do please check out Kerry’s 2021 speech about his brother - it’s quite inspirational.

So this year, when I was a speaker along with Olympian Leisel Jones and GetUp! founder Amanda Tattersall, I decided to talk about my brother, Jaz (1969-1987). It turned out to be the final Solstice in its present form, as well, I suspect, as the last time I’ll talk about my memoir - it feels, now, rather played out. As some might recall that the work first aired in draft form on Cricket Et Al last year, here’s the text of my remarks on Saturday night to complete the circle.

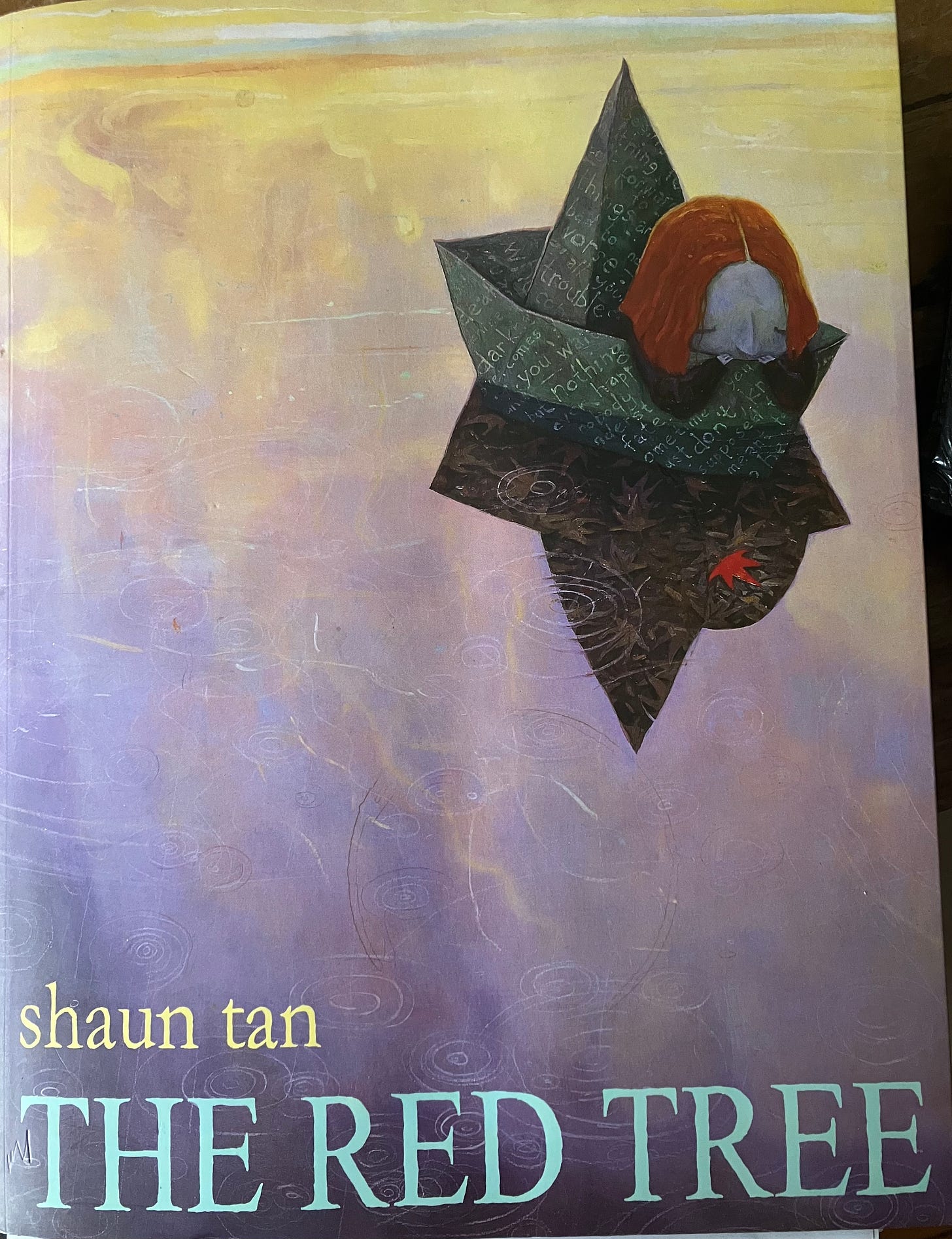

When the Bakers asked me to Winter Solstice, they were kind enough to send, contained in a copy of Shaun Tan’s The Red Tree, some samples of their late daughter Mary’s writing - her poetry and her responses to the poetry of others. Once I recognised the provenance of the contents, the item took up a place on my desk from which it could neither be removed, because it was so obviously important, nor read, because it felt so intimate. It was duly buried in the snowdrifts of work I am ceaselessly pushing through; still, I never lost track of it, and knew that at length it would work its way to the surface when the time was ripe.

This event has now expanded well beyond the honouring of Mary, and I know that the Bakers are reluctant to accent their own grief in what has become a community of loss. But it has been something to share my desk with her these last few months, to have her words, thoughts, and image within my reach. Mary was clearly a precocious intellect and spirit, sensitive beyond all reckoning. I feel sad not to have known her, but also blessed to have read her. Next year, it occurs to me, she will have been gone as long as she was here. But what a life force, that her memory has born along this event through Annette, Stuart, Zach and Henri, and improbably caught me up in it. Because while my desk, as I said, is outwardly all confusion, it makes a silent sense. For on the base of my desk lamp is also to be found a tiny velvet jewel box. Open it and you will find two items: an earring in the shape of a marijuana leaf and a lock of hair. They belonged, of course, to my brother Jaz, who died in 1987, aged seventeen. There they have been lying these many months, Mary’s words and Jaz’s relics, resisting forgetfulness as the people themselves recede into the past, and forming part of the giant communion that has brought you all here tonight.

I feel self-conscious about this invitation. I’ve written a short book about Jaz, but that does not mean I speak about him with any great facility - in some ways, I published My Brother Jaz because I write more readily than I talk. And just because you have experienced loss does not make you generally an expert; you remain expert only in your own. So I proceed in some trepidation, knowing that we are all, in our varying ways, doing our little best to live on in the face of death. But this I have to say, for it took me a long time to acknowledge: there is something about a brother.

For many years, I found it impossible to get past the cruelty of my mother losing her son, and the dignity with which she appeared to bear it. My mother was a solo parent and breadwinner for her boys, a woman with deep reserves of strength and not a shred of self-pity. She set a standard to which I could only aspire. I was consequently, extremely reluctant to quantify what Jaz’s absence cost me. Brothers commonly do not say much. Brothers communicate more readily by their deeds. But Jaz and I shared the same mix of DNA and bulk of childhood experiences. We were outwardly very different; we were inwardly variations on identical themes. In losing him, I recognise now, I lost a kind of counterweight to myself. And when a relationship so fundamental proves so perishable, further investment in others seems risky if not altogether fruitless.

Jaz was four years my junior. We were very much older and younger brother. I was earnest, biddable; he was lively, carefree. I’m bound to say I envied him, slyly. He was funny, irreverent, charismatic, made friends easily, was bright enough that he did not have to work too hard, so didn’t. I felt that older son’s pressure to make up for our father’s absence by acting as his proxy; he experienced that younger son’s ungraspable lack of a masculine example. He was big - taller and stronger than I. On the night he died, his passengers assumed he was old enough to be driving, mature enough to have wheels. In fact, he had no licence, and had stolen our mother’s car. I do not know if he took his own life. What I do know was that his driving heedlessly through a red light wasn’t out of character - he was, after all, seventeen, an age when we’re all taking risks, cutting corners. He was also, I sense, depressed - a state where you sometimes need the stimulant of danger to feel fully alive. At 1am on a weeknight in our home town of Geelong in 1987, moreover, you had to be pretty unlucky to encounter any traffic. He might easily have skated through, just missed the oncoming car, just cheated fate. A split second either way and it might have become a funny story between us, and I not here tonight.

The fact that I am is also otherwise significant. In 1987, bereavement was a silent ordeal. My memory of it begins with very sharp edges - I can describe the immediate aftermath of Jaz’s death in almost minute-by-minute detail, the spectacle of the car in the wreckers’ yard, the sight of his body in the casket. For you have not fully grasped life until you have, as it were, seen its absence.

Yet very quickly does my memory go out of focus, out of shape. I know I delivered the eulogy, but am damned if I can remember a word, and or the thrust of a single conversation afterwards - actually not for years can I recollect seriously reflecting on anything, beyond the numb trudge to the next day. My mother told me recently that about six months later in her school staffroom, somebody cracked a joke, she laughed and immediately felt ashamed. For me, there was no danger of either. I can honestly say that the next few years in my memory, otherwise capacious and retentive, is all but blank. I love reading and music. But I have books from the time I have remained unable to read, records I acquired I have never been able to listen to. I shunned friends. I moved overseas. I developed an eating disorder. I existed in a state as close to death as it was possible to be - and, to be honest, that seemed to make complete sense. Why should I live on in Jaz’s absence? And as it happened that I did, why shouldn’t it be an ordeal?

Perhaps you know this feeling also. For how are to live, we survivors? The world cannot just move on as though the lost do not matter; there must be some form of commemoration to counteract the world’s indifference. Most of us do not have the Bakers’ presence of mind and sense of purpose. Our redress, then, becomes bearing the yoke of loss - carrying with us something that, at the same time, we cannot bear to contemplate.

The only way not to think about my brother was to think about nothing at all - save work, with which I filled every available minute of every day. Where it did break through, I could make sense of it only by self-denial. I’m a writer. I write as a living, and a calling. I’ve published fifty-two books on subjects of my choosing. But I hadn’t a hope of addressing the subject silently gnawing me; I straightened my shoulders, hardened my heart, and worked like there was no tomorrow, because it often felt like I might not make it there. I could be, I confess, and my professional colleagues ad and intimate partners will attest, an exceptionally difficult person to be with, intolerantly perfectionistic at work, averse to anything savouring of comfort or pleasure at play. Even now, it is a constant battle to be otherwise.

What changed? No body, and no one thing. Taboos round the acknowledgment of grief, as Solstice affirms, have relaxed. But that did not influence me. I had good friends who were kind and supportive. But they did not reassure me. I simply started doing some things. One day I found the house where I was living in 1987 open for inspection, went in, stood on the spot where I received my mother’s telephone call that Jaz had been in an accident, and realised that the memory of that moment still lurked. One day I was in a bookshop and saw a book, The Day That Went Missing, in which the author Richard Beard described his family’s eerily muted reaction to the drowning of his younger brother on a family holiday, and it excited a pang of recognition. One day I came up with an unfocused idea to look into the history of the coroner’s office which would involve several months of reading nothing but inquests - a genre of official record with which I have always been fascinated. Only after several months of filling exercise books with notes did I reluctantly admit that this was my characteristically intellectual answer to an emotional question - that there was only one inquest in which I was genuinely interested, even assuming it existed. So I applied for the file concerning Jaz’s death. It took six months to retrieve, another six months before I had the nerve to read it closely. But it was, after all, on the page and in my head, everything I had avoided, so long and so scrupulously avoided. We fear forgetting, don’t we? We hold fast to our relics, our records, our images, our letters, because what if, one day, we should realise that the sound of our loved one’s voice, the feel of their touch, the memory of their laugh, has somehow slipped away? The fear, I found, was misplaced. I bridged thirty-seven years in a heartbeat. My Brother Jaz explains what I found there.

What do I feel now? Party of me still burns with fury. I feel cheated of my brother’s society and solidarity. He should now be fifty-five, a blood-bonded friend of mine, a rugged son to his mother, a fond uncle to my daughter. Occasionally, in fact, my daughter reminds me of him, in the shape of her face and the cant of her head. I smart from the cut this realisation leaves - it’s a reminder that I’m not quite whole and never can be. But something emerged from the seventy-two hours of writing this little book that the thirty-seven years of not writing it had prevented - I was able, at last, to slip the story between covers and set it on a shelf in the corner, where I could see its shape, study its dark lineaments, and generally separate myself from the need to carry it alone all the time. In doing so, too, I finally saw him again, my brother Jaz, the only brother I shall ever have, and whom I shall go on missing everyday for the rest of my life.

Do please donate to this fabulous charity. It supports great services and has great partners.

No comment of mine could do this essay justice. Beautiful.

Thank you Gideon- all I can say is that my younger son attempted suicide & thank God changed his mind at the last minute