Blazers and Horizons

Foreign privateers are aggressively re-shaping professional cricket. Does Australian cricket have a vision?

Sam Perry

Last summer, ahead of the West Indies and South Africa’s respective visits, many of us chin-stroked with concern about looming flat notes. But if you were an interloper among the powerbrokers and impresarios inside cricket, last summer was going to be fine. The current summer was the one to worry about.

It made sense. Consecutive seasons of have-not visitors. Another middling BBL with transient players. The walls closing on summer’s real estate: footy on one side; rich, smoky, overseas franchise gatherings on the other. In Australia, we hardly know what these competitions look like. We barely know what they’re called. We just know that they exist, because the best players – if presented the choice – generally prefer to be there than here.

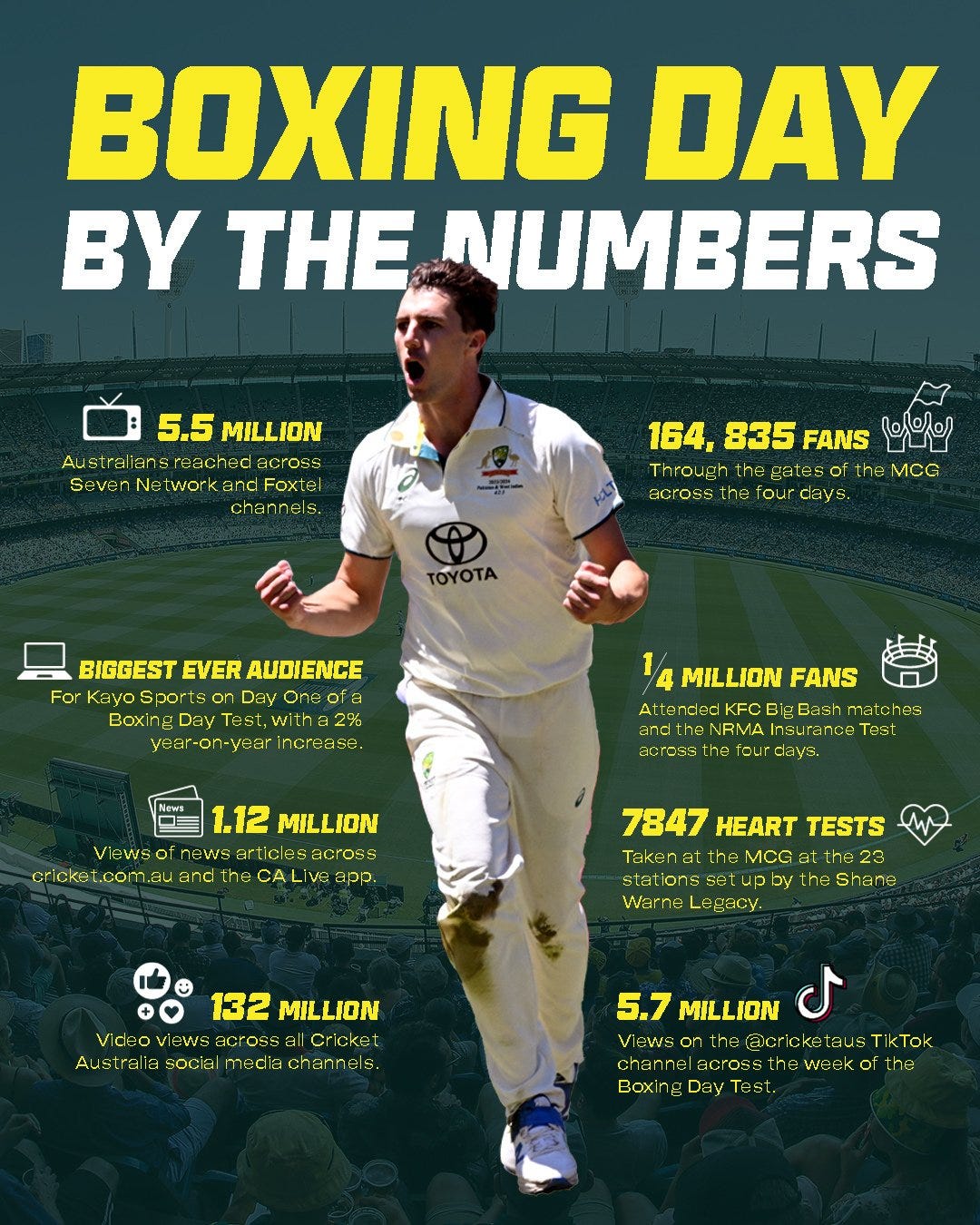

To some, this alarmism might be growing tedious and overstated. Crowds for “International 2’s” have soundly beaten expectations. So too has the BBL. TV numbers are healthy. Perhaps the demise of long-form cricket is exaggerated and there is life in this thing, yet. The BBL captures the kids. Red ball cricket runs deep. The ABCs PO Box is literally 9994. There has always been life, and there always will be.

To that end, Australia’s administrators deserve credit. Here, you still need to squint a little to see evidence of cricket’s upheaval, at precisely the time of year we’d prefer our eyes closed. For all the pearl-clutched, doomsday warning, it’s still eminently possible to let the cricket wash in a way that threads the past and present. All of Australia’s teams are good. Familiar names pile up milestones. Punter predicts things. Great West Indians are replayed. Mid-strength drinkers count down from ten, and we hear their twang echo through the grandstand over the airwave. Kids are playing. Annual heavyweight contests aren’t needed for these things. Maybe a Gratitude Journal [of a Cricket Mum] would be better.

But the upheaval is happening. I recently spoke with a number of cricket administrators, as well as people who’ve worked with and against them. Some current, others former, at all layers of the game, and exclusively on background so they could speak freely. As expected, perspectives didn’t always dovetail, though many expressed concern about my choice of subject matter. When I told one that I wanted to write about “the experience of administrators”, they replied drolly, “sounds electrifying”.

Back in the day, the trope of the administrator went like this: man, blazer, white hair, probably out-of-touch. He might’ve been the best in the country before midday, and its worst after. Appearances are a little sharper today, but there is connecting fibre. They are largely regarded with scepticism. As one said to me, “People think administrators wake up every morning and ask themselves, ‘how do I destroy cricket today?’”

However, most I spoke with felt Australian administrators generally carried a sense of responsibility beyond profit, were cognisant of opportunities and threats to the game, philosophical about what thriving cricket looks like, but concerned about structural forces that prevent long-term decision making.

That matters, because foreign, private enterprise is rapidly buying up the Monopoly board, without compunction for Anglospheric tradition and heritage. In the last 18 months, privateers have largely driven the establishment of the ILT20 (which was the primary driver for the BBL’s shortened season), the SA20, the inception of America’s MLC last July, IPL regular season expansion, and a mooted IPL T10 expansion in September-October. That’s before we get to looming Saudi investment.

A rough calculation estimates seven months of the calendar year is effectively monopolised by IPL and satellite IPL franchises. In response, administrative rhetoric appears to be focusing on solving this saturation via scheduling, per Nick Hockley on The Final Word. However, wouldn’t more time mean more real estate for franchises to capitalise upon?

Therein lies the structural concern. The goals of private enterprise are clear. Profit-driven, 5-7 year horizons, exits with surplus. National administrators, on the other hand, operate on 3-4 year cycles with popularly elected Boards. As one tells me, “It’s hard to be popular trying to sell a 10-15-20 year vision”. Commercial or career incentives militate towards short-termism, driving focus on immediate profit, which in-turn drives re-appointments and re-elections. Who wants to be the person disrupting Australia’s summer? It’s better to kick the can down the road, make some money, and get out. “This is the dilemma of modern politics”, a former administrator told me. Long-term visions frustrate powerbrokers in this environment, and governance models disincentivise it.

Should Australia be looking to re-shape its summer? Perhaps this has always been happening. In considering the rise of short-form, franchise-centred cricket against legacy versions of the game, one administrator reflected on Seymour Skinner’s famed line: “Am I so out of touch? No, it’s the children who are wrong.” And Abe Simpson, who said: “I used to be with it. But then they changed what it was. Now what I’m with isn’t it, and what’s it seems weird and scary to me. It’ll happen to you!” When was cricket “correct”? Timeless Tests? Eight ball overs? The Packer Years? Amateur Women’s cricket? Our biases often skew to that which we first fell in love with. There are more people watching than ever, there’s more money than ever, and the game is being packaged appropriately to the evolution of the world around us.

It was a thought echoed by club administrators, too. For so many, they joined a club determined to avoid its administration, only to find themselves President some years later. “I tried to avoid it, but I can’t help it,” one said. They’ve suffered losses of players, who are craving more T20 cricket, not less, so as to keep their jobs, study, and run their lives around it. While there are fewer professional and State players every Saturday, facilities are better, players train both smarter and harder, but they’re looking for a competition that reflects the direction of the game. “Why do we play so much two day cricket?” one said, before noting that many club administrators “don’t look like, or understand well, the players they organise.”

Most spoke of capability, responsibility, and goodwill among administrators in Australia, that sat alongside a growing disquiet about Australia’s posture toward mercantilist private enterprise. Does a federated, public, community-based model have a chance against the power of private enterprise? Can collective desire be mustered to push back, anyhow? Are we beating them? Are we joining them? And is it possible for any of our leaders to enact the Indian proverb: “blessed is he who plants trees under whose shade he will never sit”? It would be great to know.

Raises all the important issues without (inevitably) answering or (sadly) even prognosicating much about the direction of travel or end game for test cricket and the sport broadly. Hopefully that will be in future pieces.

For mine the popular culture references for our future are "aye it's cricket Jim, but not as we know it". Sport is the continuation of politics and business (now inseparable) by other means. "It's the economy, stupid". Follow the money.

What India wants, India gets. Its population, eyeballs and economic heft dictate that. Modi and MBS in Saudi are the swing states in the looming economic, cultural and physical wars between the West (US, UK, Western Europe, Oz et al) and the authoritarian China and Russia empires.

I'm not optimistic about Test cricket having a shelf life beyond 10 years in that world. Concentrated private wealth and shorter time and attention spans mitigate against it.

Geopolitics and the entertainment/media industry will shape cricket and other sports much more than any administrators, boards or the ICC.

Kricket and Kapital, by Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels