Cricket BC and AD

Broadcasting legend David Hill joins Cricket et al to pay tribute to Brian Morelli, who pioneered the way cricket looks and feels on TV.

When I was writing The Cricket War many decades ago, Ian Chappell recommended I interview Brian Morelli. I only dimly knew the name of the director of World Series Cricket’s television coverage, but it proved inspired advice. Brian could hardly have been more gracious to the young reporter I then was; spent an afternoon talking me through philosophies and sharing anecdotes. He sent me videos, read passages for me, was the complete gent - and last week he passed away, aged eighty-eight. Coincidentally, I’d recently been in touch with his storied producer, David Hill AM, now resident in LA after a career producing everything from NFL to the Oscars, and he volunteered this splendid and insightful tribute, which goes a long way to explaining the revolution that WSC portended in the coverage of live cricket. A lot of those things we now take for granted about the cricket on our televisions had first to be invented - and Brian, with David, helped invent them. Gideon Haigh

Tribute to Brian Morelli

David Hill

A part of cricketing history died the other day. He never wore the baggy green, he never represented his state. You won’t find his name emblazoned on any list. Yet he had a more profound impact on cricket – the way millions of us watch the game – than anyone. His name was Brian C. Morelli, and he was a television director.

First, though, let me explain what a director does, because no one who doesn’t work in the business can know quite how challenging it is. You need a pretty big arsenal. Split second reflexes for a start, because you’re reacting to what happens. A total understanding of the game; knowledge of all the laws, no matter how obtuse; knowledge of the players and their idiosyncrasies; just as a good carpenter knows his tools, a director has to know all the engineering mysteries of his broadcast van, and a 6th sense when something’s about to break (which it will); has a strong rapport with his camera operators – who in turn need to trust their director; understands the constant flow of graphics – the messages which update the various aspects of the game being covered, and more importantly the content of the graphics; what’s happening to the audio – are the commentators being stepped on by the ambient fx? – should we be hearing those fx mics better?; the director’s replay operators, because they have to have that replay standing by literally seconds after an action which warrants replay happens; and the ongoing dialogue with the commentators, telling them through their IFBs what shots are coming on screen, what replays are coming up, and occasionally to shut the hell up, let’s listen to the crowd!

Take a moment, and think of an orchestra. Upward of 80 highly skilled musicians, their eyes switching between the score, and the conductor, the maestro, whom - through total command of the piece - with artistry, showmanship, maybe a touch of magic, puts those 80 highly skilled individuals to the work they love, and blends their output into one cohesive, evocative, moving emotional experience for the audience.

I guess that’s the best way to describe what a director does – the centerpiece in the broadcast van, or the OB (outside broadcast) van – depending what country you’re working in – who is calling the shots, with a small army of specialists, working under pressure, combining to produce the telecast. And, all remembering that the key to what they do is transparency.

Millions, sometimes billions, of people switch on their media devices to watch a sports event, and they should never be aware of how it comes about. Every time the shot changes, every time a graphic comes on screen it happens because the director calls it. Make one mistake, interrupt the flow of pictures, which are telling the story of the game, the juxtaposition of images which make up the broadcast, and those millions are aware that something’s wrong, something went astray, and momentarily the magic is broken, and they’re back in their living rooms – not attuned to whatever battle is taking place on the field of play.

In 1977, Kerry Francis Bullmore Packer, with some help, decided to start World Series Cricket. The story of how that came about, with Richie Benaud, John Cornell, Austin Robertson and Lynton Taylor has been told countless times in story, books, movies and I guess if you count ‘C’mon Aussie C’mon’ in song too. What was lost in all the alarums and excursions,was that it was all about the television coverage. There was only one glaringly obvious problem to anyone paying attention. Channel 9 did not have a cricket production unit. Oops.

What they did have was a remarkably efficient outside broadcast unit, led by Warren Berkery. And a staff director. Brian C. Morelli. And that was it. There was another director, hired by WSC – the Perth based John Crilly – but he’d had it after the tumultuous first year, and retired back to the west coast.

I was hired as the Executive Producer, and arrived at TCN9 Sydney in August. 1977. Did I know anything about cricket? No. Had I ever produced live sports television? No. Did anyone ask those questions? No. We were on the air in November. But that’s not for this story.

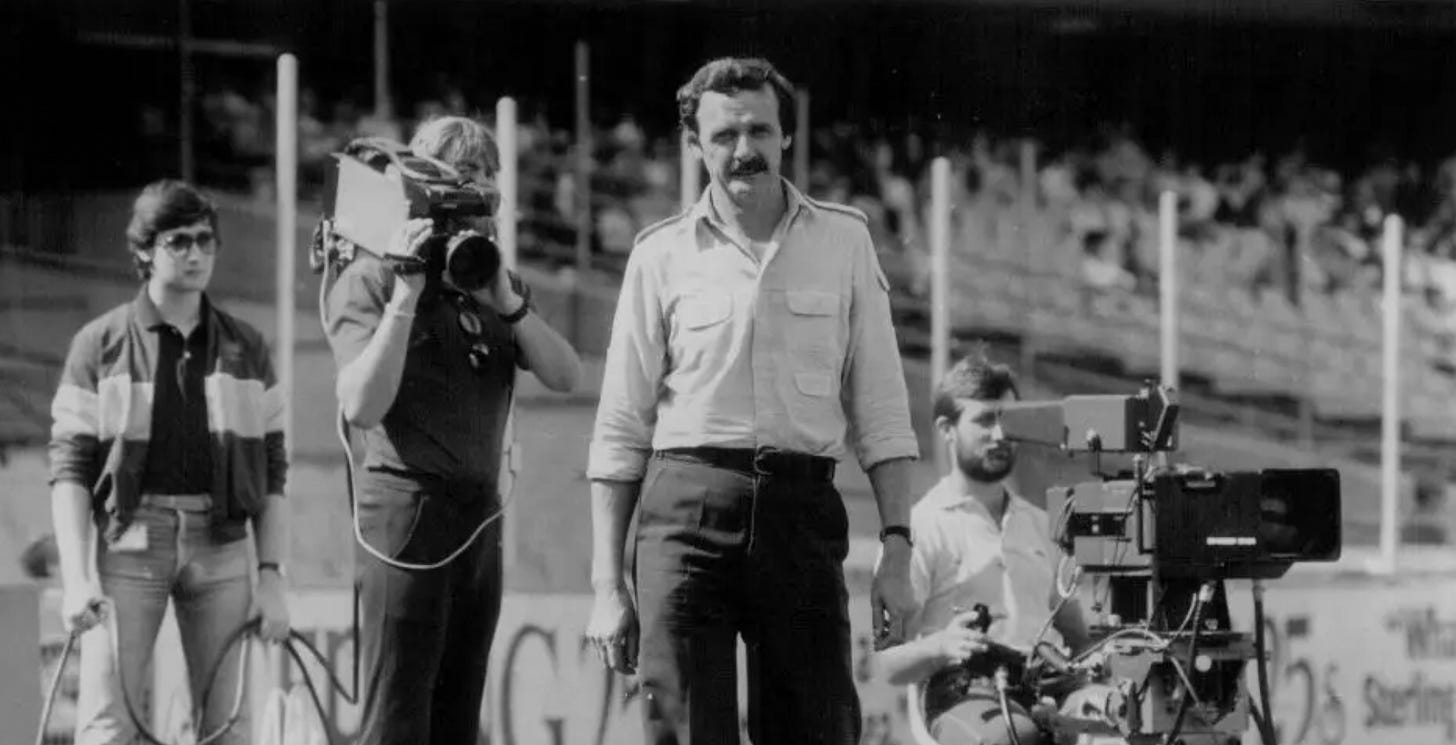

So I meet Brian Morelli for the first time. A slender, handsome man, with intense dark eyes. Obviously intelligent, with an easy smile, and what I was to discover was a wonderfully quick sardonic sense of humor. I was in my early 30s, Brian in his early 40s, and we were to be joined at the hip for the next 11 years. His philosophy about television was simple. “Every minute you’re on air, is the most important in your life” – and it was that quest for continuing excellence that Brian was able to instill into everyone with whom he worked.

Back in the days when Australia had National Service, BC served in the RAAF where he developed photographic skills. He was a trained still photographer, after the RAAF, he worked for the NSW Government – and one of his gigs was documenting the construction of the mighty Warragamba Dam. And I firmly believe it was that old school photographic training, using a heavy Speed Graphic, that gave BC his intuitive framing ability. His understanding of in frame composition, and his uncanny ability to juxtapose shots into a flowing montage which told a story had its origins in his early training. He’d joined TCN9 early on, and segued into television, like the pro he was. My background was journalism, newspapers and television.

Kerry Packer’s mandate was simple. Make it great. Make cricket exciting. Make cricket dramatic. Make it popular. Don’t make it like the BBC’s coverage. So we started with camera positions. Both end coverage, naturally, low angle slips cameras, low mid wicket, let’s bring viewers the sounds, so we buried microphones in the ground, until the cricketers discovered them, and stamped on them! Which led to popping a radio microphone in a stump.

What I soon discovered about Brian was that he was a fierce competitor, and even better, wanted to push the chips into the centre of the table. So the conversations were endless. In the car on the way to the ground, in the bar at night, over a few beers, on planes, at dinner with Richie, at lunch with Warren Berkery. How do we make it better? How do we translate the excitement to the viewer at home? What are we missing?

And season by season, Brian just kept getting better. What was interesting was that in those early days the crews travelled with the cricketers. So we would be hanging with Vivi Richards, or Clive Lloyd, or Ian Chappell. Friendships developed – one of the strongest between the West Indies Joel Garner and Warwick Bull – who had to be the best midwicket cameraman ever. And what that did was the cricketers weren’t just objects, we knew who these guys were, and there was this strange emotional bond between the crew and the cricketers. And when I look back at the coverage, oddly enough, that connection came through. The crew cared. And were in awe and admiration for Kerry’s ambition.

We started Season 2 to the sounds of C’mon Aussie C’mon, and the brilliant floodlights of the SCG. Year one has been tough. Most of the time we played before very spare crowds – sometimes the word ‘crowd’ was a major exaggeration. And we were still getting our rhythm, still working out what we needed to do to get better, still realizing that we HAD to get it right, otherwise Kerry’s Great Dream was doomed, and in the first ODI at the SCG, that season, Brian and I walked down to dinner as normal, to do our post mortem of the afternoon’s coverage. The crowd that afternoon had been good, but nothing prepared us for the sight as we walked back outside. The SCG lights were on, and the ground was packed. Not just packed - crammed. The noise. It was a hugely emotional moment. Brian croaked – “I think we’ve won” and teared up – as I did. We went back to work for the second innings, inspired.

Let me return to my orchestra analogy. If Brian was a conductor, he was Leonard Bernstein. No exaggeration. He had the ability to get the best out of the crew, to keep things light, even in the most tense circumstances. His direction was crystal clear, no hesitation, and he seemed to have peripheral vision, outside the range of the cameras. He’d pull the most unexpected of shots, which would advance the story we were telling – either adding drama, or humour, or pathos - and the Richie could rely on him for, well, what became known as ‘Richie stuff”.

Richie: 'Ah, BC, would you mind getting me Bedi’s second delivery in his third over please?'

BC: 'Yes Richie.'

Pause

BC: 'Got it.'

Richie: 'Righto. Hang onto it.'

Overs would pass. Then.

Richie: 'Right, BC, let’s have the Bedi piece.'

BC would roll tape with Richie’s VO. 'I think Bishen’s realised he needs another delivery just like this one.'

Bedi would take a wicket with his next delivery.

Richie: 'Got him!'

By the third season, we were cooking. The morning pitch report, Tony Greig very gingerly at first, but getting better, Jane Prior’s graphics working, Peter Fragar’s audio working, especially the stump microphones; the commentators coalescing into a genuine team, and in the middle, like the conductor, was Brian Morelli, calling the shots.

He’d make marginal shifts to camera positions, spend hours working with Warren Berkery on technical improvements, always with the aim of making our telecasts better. Not sure if he was a big fan of Daddles, our animated duck for when a batsman was dismissed without scoring, when I first introduced him, but he learnt to love him!

By now, BC and I were a team, cricket ratings were booming, and, after all the crap we’d put up with (mainly from UK cricket writers - and especially the BBC’s Head of Sport, Jonathon Martin, who said it would be a cold day in hell before the BBC's cricket coverage looked like Channel 9) about the style we’d developed, it was gratifying for us both. Especially when we got into London one day (I think setting up our Wimbledon coverage) when we found the BBC were using our camera positions!

Then, things hotted up, and BC came into his own. We never stopped. Channel 9’s Wide World of Sports came into being when we bought the Australian rights to the name from ABC). We were off to the races. Literally. The iconic WWOS Saturday afternoons with Mike Gibson and Ian Chappell, which soon went Australia wide, which opened the floodgates for top international sports coming to Australia. Tennis tournaments (Wimbledon, French, US), Formula One races, golf tournaments, horse races - if it was top international sport, it was on WWOS. And then, come summer, we were on the road producing cricket.

We never saw our families. Home was the Control Room of Studio 2 at TCN9 in Willoughby. Pre production in one of the ramshackle cottages surrounding the studio (which became the Sports Cottage), then either hit the road to produce on site, or head across the car park to the studio. Don’t drop the rundown on the way!

Then we were into Rugby League, and here BC came into his own. What we’d done to cricket, we wanted to do to Rugby League, and as a fan (Balmain was his team) knew the game back to front. He totally reorganised the camera grid, making the coverage so much more dynamic, instituted steadycam sideline cameras (where Toby Phillips shone), slammed in replays – all the while keeping up a running commentary while calling shots which was both hysterical and slanderous. BC’s commentary, I hasten to point out, was only heard by the crew, but there were times it was so on point, and so funny, that I felt it was unfortunate we weren’t broadcasting it. I guess even Kerry couldn’t have afforded the lawsuits.

And the showing his total versatility, he and I were handed The Two Ronnies Down Under – a total departure from what we’d been doing, and of course Brian handled everything magnificently. He worked for months with Ronnie Barker and Ronnie Corbett, shooting the inserts, then worked with Ronnie Barker on the edits; then the finished shows. Barker paid him a huge compliment, saying that Brian was the best director he’d worked with. High praise indeed.

Then, as well as everything else we were doing, along came the first Australian F1 Grand Prix in Adelaide. Huge logistic technical undertaking, handled superbly by Warren Berkery and his crew (props to Sally Goodman) . BC was in his element, and Channel 9, to our great surprise, received Bernie Ecclestone’s award for best coverage of the season. But our real reward came at an award ceremony in Paris, when the world champion Alain Prost asked: 'How did you make the cars go faster?' Simple. It was the way BC had positioned the cameras, and the way he cut his shots, which showed, probably for the first time, just how dynamic F1 racing could be – if covered the Brian Morelli way.

1988 came, and he and I said our farewells, and I took off for adventures overseas. But friendship doesn’t say goodbye, and we stayed in touch. And in his final hours, I let him know that his legacy was enduring and world wide.

Simply because I took the lessons that Brian had taught me, and implemented them in the coverage of everything I handled - from the EPL, to the NFL, to MLB, and to Formula One. There are sports fans all round the world, enjoying the coverage, of what ever sport they love, not aware that the seeds of that coverage were created and nurtured by Brian C. Morelli.

And if you’re a cricket fan, next time you’re watching a game, just reflect, if only for a moment, on the man who sat there, like an orchestral conductor in his broadcast van, and created the template for what you’re watching and enjoying today.

Vale Brian Carl Morelli.

That was a fine tribute, David. Even though I spent many years in broadcasting, I find it easy to forget the maestros of the OB when lost in the game.

Sports coverage continues to improve as does the ‘magic’ of technology you describe. The first Australia v Pakistan test was terrific viewing. The OB guys are still working overtime.

Thanks for relating Brian’s story. It made me regret that I never met him. Or you for that matter!

Brian was my uncle, my dad's brother, the youngest of his parents seven children. I have many fine memories of him, incl. his having me included in the audience of many Chanel Nine TV shows, both in the chanel nine studios and other outside venues. He promoted me to contestant on Cabbage Quiz with Desmond Tester and Penny Spence many years ago. We lost touch over the years but I always happily claimed him as my uncle whenever the chance popped up and am always grateful for his kindnesses.

Vale "uncle Brian".