Cricket Narratives

A paper by Et Al subscriber Paul Giles

Paul Giles is a professor of English in the Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences at Australian Catholic University. If he’ll pardon me saying also bears a resemblance to Jacques Derrida, which he unusually couples with an excellent working knowledge of Essex cricket. So he was well-qualified last week to deliver the following lecture….

…to which he invited me to respond. This was a pleasure, given his thorough reading of cricket’s canonical works. He’s been kind enough to permit me to publish his paper here - I’ll follow with my response tomorrow. GH

Thank you for coming this evening, and I’d like to acknowledge the people of the Wurundjeri nation on whose lands we meet, and pay my respects to elders, past, present and emerging. I’d also like to particularly welcome Gideon Haigh, who has written prolifically about cricket and was described recently by former England cricket captain and London Times correspondent Michael Atherton as “the best living cricket writer,” a recommendation endorsed in 2019 by Wisden Cricket Monthly which called him “the game’s most eminent current voice.” Gideon mentioned in one of his books that the Australian batsman Victor Trumper, who died in 1915, was the first Australian to be recognized as the best in the world at anything, and he himself can be said to have replicated that in the field of cricket writing. My own credentials for discussing this topic are much less storied, though I have had a long-standing interest in the game, having been first taken by my father at the age of seven to a Test match between England and South Africa at Kennington Oval in London on Saturday 27th August 1965, over 60 years ago now, when I remember Colin Cowdrey and Jim Parks resuming the England innings and Eddie Barlow bowling for South Africa. I also attended several county games in Essex during my youth, going back as far as the last strains of Trevor Bailey in the mid-1960s through to the glorious Indian summer of Graham Gooch, though I would not categorize myself as a “cricket tragic.” What I want to do in this talk is to consider more analytically some of the ways cricket has been represented in literature and culture, and how sport in general intersects with wider social currents in Australia and elsewhere. Particular kinds of narratives, both fictional and non-fictional, have developed around cricket in recent times, and it is valuable to consider how they might be understood in relation not only to academic interests but also broader cultural landscapes

In his famous book Beyond a Boundary, originally published in 1963, the West Indian-born cultural critic C.L.R. James argued that sport had been unduly neglected by mainstream historians, complaining of how G. M. Trevelyan never even mentioned in any of his books on Victorian England the entrepreneurial cricketer W. G. Grace, whom James claims was “the best-known Englishman of his time.” There are fairly obvious explanations for this kind of oversight, including traditional forms of academic specialization, which can sometimes miss important connections, as well as cultural hierarchies that have often positioned sport at the bottom of the pile. (The Australian novelist Thomas Keneally characterized sport as the “grand opera of the proletariat.”) The same kind of hierarchies have shadowed and perhaps distorted how history itself has been articulated. In an academic article published in 1973, historian W. F. Mandle argued that the move towards Federation in Australia towards the end of the 19th century was driven more by the kind of broad national feeling derived from international cricket matches played against England rather than the legal intricacies about governance that most of the population then were not very interested in. Mandle pointed out the Australian side that toured England in 1884 carried an Australian coat of arms seventeen years before Federation, and after Australia’s victory in the 1898 test series the Sydney Bulletin wrote that “this ruthless rout of English cricket will do—and has done—more to enhance the cause of Australian nationality than could ever be achieved by miles of erudite essays and impassioned appeal.” Qadri Ismail made a similar point about the development of West Indian nationalism in the years after World War II, that it found its voice most powerfully not through organized political groups but through cricket, with Viv Richards being one of those who famously brought an anticolonial brio to his destructive batting performances. The more recent rise in India’s cricketing status has also been impelled in part by a desire to bite back at Britain’s imperial legacy, with one of their star batsmen, Rahul Dravid, telling a journalist in 2002 that his preferred incarnation in a former life would have been as “one of the leaders in the Indian freedom struggle.”

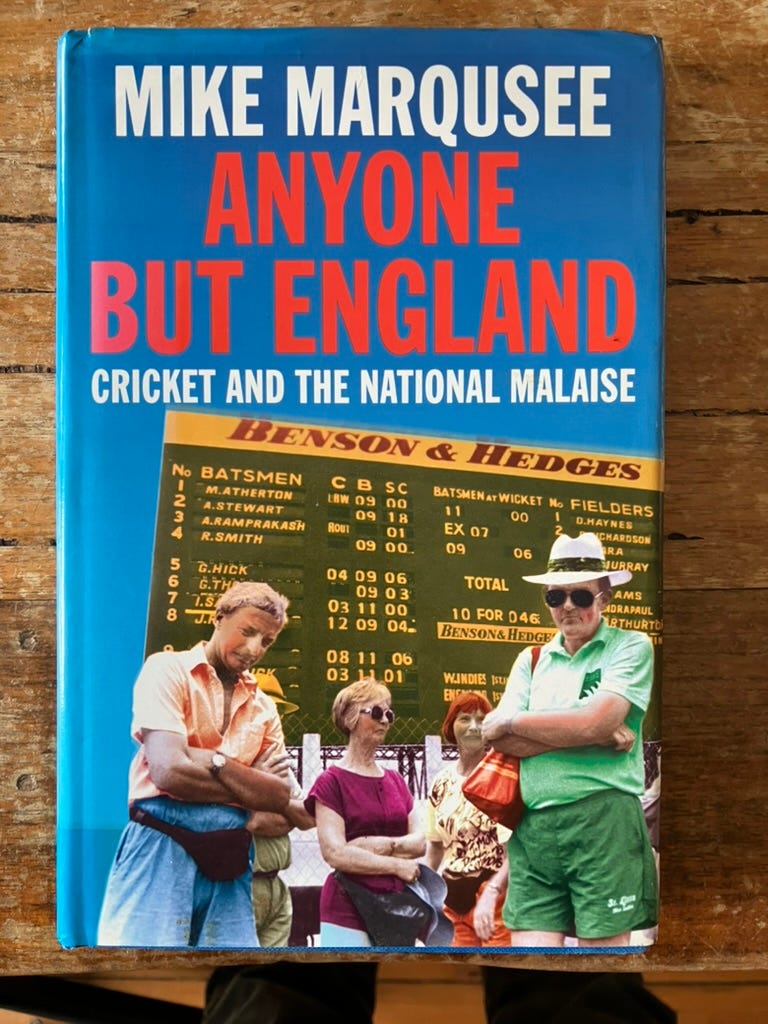

As C.L.R. James noted, it has not always been the case that there has been such compartmentalization between sport and academic or political culture. Brian Matthews, who was a pioneering scholar of Australian literature, chose as the subject of his last published book in 2016 the Australian cricket captain and commentator Richie Benaud, while James cited Plato and Pythagoras attending the Olympic Games in Ancient Greece, where Herodotus somewhat mind-bogglingly “tried out the new art of history by reading his early chapters to the crowd.” One of the interesting aspects of James’s career was that he lived in multiple locations—born in Trinidad, but in England between 1932 and 1938 and then in the United States until 1953, before returning to Britain—and so he was able to frame his interest in cricket within a comparative framework. There is a bifocal perspective in Beyond a Boundary through which James compares cricket to American baseball, and the same thing is true of another important work on cricket, Mike Marqusee’s Anyone But England, which was first published by the political press Verso in 1994. Subtitled “An Outsider Looks at English Cricket,” and written by a self-described “deracinated Marxist of American Jewish background,” Marqusee analysed the various forms of social and racial discrimination that had shaped the game from its earliest days in largely unconscious ways. The book’s impact within the cricket world was similar to that in the academic sphere of Edward Said’s Orientalism, published in 1978, which suggested ways in which condescending stereotypes about the inferiority of the East had helped to shape the Western cultural tradition. Said cited C.L.R. James’s work on the American author Herman Melville, but he said nothing about his interests in cricket, perhaps because as a professor at Columbia University in New York this fell outside Said’s frame of reference, but perhaps also because of the implicit cultural hierarchies to which I referred earlier. Like James, Marqusee referred frequently to baseball, arguing that “you simply cannot understand one game (or one society) without referring to another,” and he compared the way the all-Black West Indian cricket team of 1976 “blew away” Tony Greig’s all-white team of Englishmen to Jackie Robinson breaking the colour bar in American baseball when he played for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947.

In the wake of Marqusee’s work, there has been a lot of academic writing since the turn of the 21st century on the postcolonial directions of cricket, its links with empire and so on, and I don’t want to go over too much of that ground again here. It is undoubtedly true that there has been a fundamental shift in cricket’s global balance of power from the Imperial Cricket Conference that governed the game a hundred years ago, based around the triad of England, Australia and South Africa, to a new dispensation shaped by England, Australia and India, where India has become the dominant partner largely because of the massive television revenues generated by the Indian Premier League. The well-known Indian sociologist Arjun Appadurai, who now works in the United States, wrote in 1995 of how “television has completely transformed cricket culture in India,” bringing it to a much wider audience, so that “its rules and rhythms,” as he put it, have “become part of vernacular pragmatics.” Amit Gupta also suggested that the “globalization of cricket” has marked “the rise of the non-West,” reflecting a different model of globalization: not one spreading from West to East, as in American or European visions of a new world order, but in the opposite direction, from East to West. It was this countercurrent that led BBC cricket correspondent Christopher Martin Jenkins in 1992 to express concern at the growing influence of what he called, in an unfortunate phrase, “the Oriental lobby.” Television has of course been central to this globalization process, with matches readily beamed around the world, and revenues from television rights now being far more important to the economic infrastructure of cricket than gate receipts.

But while political critiques of cricket are not inherently wrong, they risk often becoming too repetitive, like many other forms of academic discourse, and so often fail to catch the idiosyncratic character of cricket that distinguishes it from other kinds of cultural activity. I’m more interested here in thinking about some of the crossovers and juxtapositions that, I would argue, characterize the flexible, heterogeneous nature of cricket and cricket narratives. Some of you may be familiar with Sir Pelham Warner, who was born in Trinidad, educated at Oxford, captained the England team on its tours of Australia in 1902 and 1911, and was then manager of England during the infamous “Bodyline” tour of 1932, when Douglas Jardine was captain of England and instructed his bowlers to aim directly at the bodies of Donald Bradman and others, in an attempt to prevent them scoring freely. (C.L.R. James, incidentally, aligned this bodyline tactic with what he called the “totalitarian” politics of the early 1930s, with its deliberate cultivation of what he called a “brutality of set purpose”). Less well known, however, is that Sir Pelham Warner was the grandfather of the well-known contemporary cultural critic Dame Marina Warner, who has written autobiographical pieces about visiting her grandfather in his South Kensington flat after World War II and recalling how, for her, he embodied “history, not only a chapter of cricketing history, but also many loops and knots to do with England and abroad, with ideas about where one belongs and who one is.” Marina Warner’s academic specialty is visual art and mythology, and in 2012 she served at Oxford as a PhD examiner for Christian Thompson, the first Australian indigenous student to graduate from there, with Warner later contributing a catalogue essay for an exhibition of his works.

I am not, of course, claiming a direct kinship between Sir Pelham Warner and Christian Thompson, but I do think it’s worth noting how what Marina Warner calls the “loops and knots” endemic to the tangled course of Anglophone history are also embodied imaginatively within the multifaceted structures of cricket. In 1901, the playing and watching of cricket as a “foreign” sport was banned by the Gaelic Athletic Association in Ireland, but the more cosmopolitan Irish writer James Joyce was a keen cricket enthusiast who never took too much notice of strictures from the Gaelic League. Joyce’s brother Stanislaus, who bowled to the author in their back garden when they were children, recalled how he “eagerly studied the feats of Ranji and Fry, Trumper and Spofforth,” famous players from the Edwardian era, and a passage of Joyce’s final experimental novel Finnegans Wake brings various cricketing characters into a chain of punning analogies, mixing together Spofforth and Trumper with Gilbert Jessop and Jack Hobbs under the sign of “hale King Willow.” This overlap between cricket and modernism is, I think, different in kind from the rather flat descriptions of cricket as simply a branch of imperial politics that have been recycled perhaps too frequently in recent years.

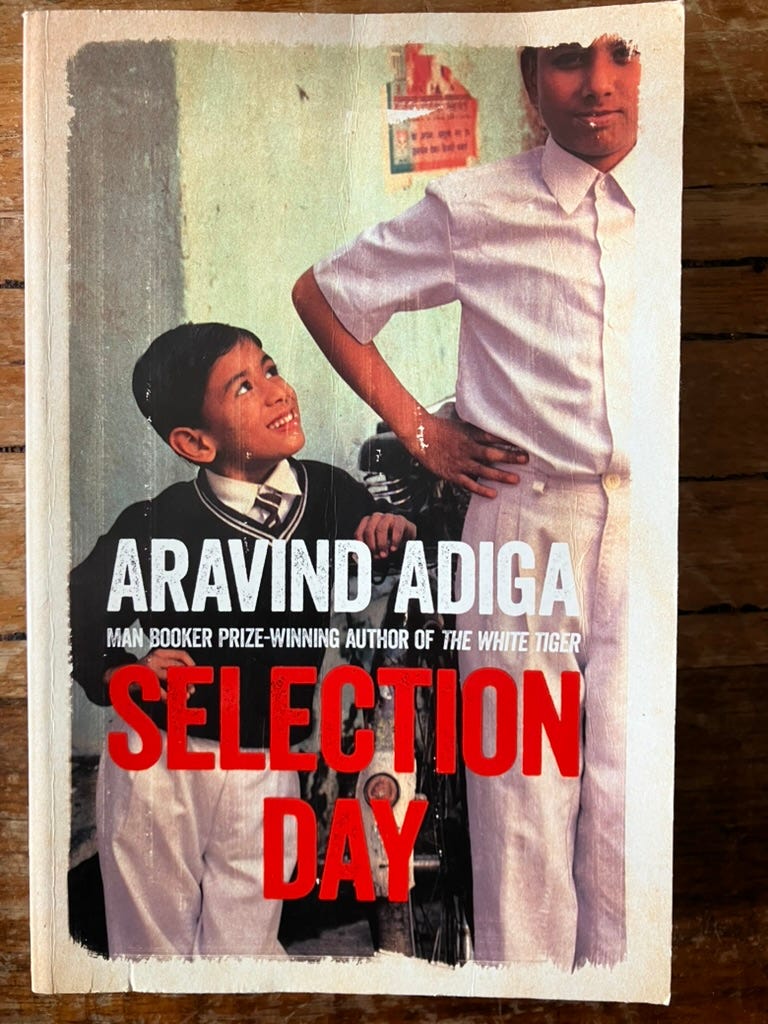

The recent shift of emphasis in the cricket world from an Anglo-Australian axis to one centred more around India and other parts of Asia uncannily mirrors a similar shift in the academic study of literature, where, under the influence of Edward Said and others, the adjective “English” now refers more frequently to a language rather than a nation, and the field itself has been dispersed into a cultural universe of multiple geographic centres. Mumbai-born novelist Salman Rushdie has been a key figure in this transition, and his 1996 novel The Moor’s Last Sigh features an entrepreneur called Ramon Fielding, who is obsessed with promoting cricket as an expression of communal Hindu spirit in order to enhance his political ambitions. Some of the best fictional treatments of cricket in recent years have come from Asia, though they have often been from authors, like Rushdie, native to Asia but with strong transnational ties to other cultures. For example, I think one of the most challenging cricket novels of recent times has been the 2016 Selection Day by Aravind Adiga, the Indian writer who studied English literature at Oxford and Columbia University in New York before returning to India, and who won the Booker Prize in 2008 for his novel The White Tiger.

His Selection Day is less well-known, but it uses cricket as both an exemplification and a metaphor for the changing conditions of Indian society and its relation to the wider world. The narrative focuses on two boys brought up under ferocious pressure from their father to succeed in cricket, with what is called here the “prison bars” of his pedagogical and coaching regime driven not only by dreams of glory but also the prospect of immense riches for the family. Adiga chronicles the shift from what is called “the old socialist economy” that was in place in India before 1991 to one driven instead by cut-throat competition and social media: “Doing well in Mumbai is nothing,” says the cricket coach: “being noticed while you do well is everything,” so that cricket becomes part of is called here “the great nastiness.” This eventually leads the young protagonists into conflict with their elders along with confusion about their emerging sexuality, with one of the young stars, Javed, concluding that “cricket is just brain-control.”

One of the things to which Selection Day is highly attuned is the psychological risks associated with the intensity of sports training in a world where success offers tantalizing material rewards, but failure is equally possible. The American author David Foster Wallace has some brilliant essays about the soul-crushing damage incurred by people who sacrifice their childhood for long days of tennis practice but then turn out to be not quite good enough to make it on to the “show,” as they call the professional tennis circuit. Adiga’s novel similarly unpacks the complex relation of sport and society in a global media age, and this differentiates it from the great bulk of cricket biographies and autobiographies written by or in collaboration with famous players, which are nearly always narratives of success, recalling how players encounter obstacles in their youth but eventually overcame them on their way to triumph. There are often interesting elements here about the player’s personal life, but the title of Glenn McGrath’s autobiography, Test of Will, is indicative of their general trajectory, indicating that challenges are always there to be overcome by the player’s resilience and willpower.

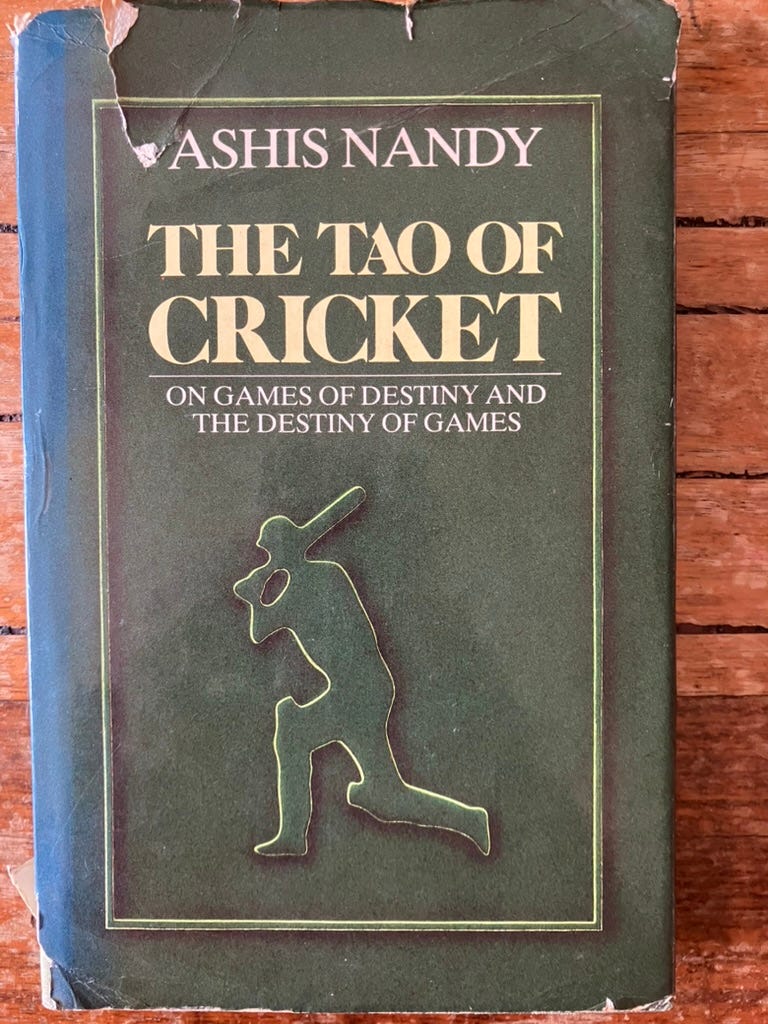

Again, there are exceptions here, and Christian Ryan’s 2010 biography of Kim Hughes entitled Golden Boy, which is not a collaboration with the subject but a more historical account of how Hughes’s priorities as Australian cricket captain in the 1980s differed from those of the Chappell brothers and other players around him, introduces more complexities that interestingly reflect the cultural clashes of that time, and indeed Wisden in 2019 declared it to be the best cricket book ever written. But a more systematic academic approach is taken by the Indian polymath Ashis Nandy, who in his book The Tao of Cricket outlined ways in which cricket involves what Nandy calls a “structure of fate,” where there are many unpredictable elements—the weather, the toss, and so on—and where there is a corresponding emphasis among the players on an invocation of magic, which normally expresses itself through rituals of superstition.

The Indian Test cricketer Krishnamachari Srikkanth said in 1986 that he believed 90% of all cricketers were superstitious, and this supports Nandy’s assertion that cricket is “a game of luck that has to be played as if it were a game of skill.” Writing in 1989, he argued that the extended length of Test match cricket in particular made it difficult to bring it “within the ambit of modern science,” given the variable pitch and weather conditions over five days and thirty hours of play

This interweaving of cricket with questions of luck and chance has a long and complicated history. As Marqusee observed, “the toss in cricket is more important in determining the result of matches than in any other sport.” In most other contests the toss involves simply a question of priority in choosing ends, as in football, or the privilege of moving first with the white pieces, as in chess. But in every football game the teams change ends at half time, and in chess there is no question of tossing up again before each game: the initial toss simply decides who goes first, and the players swop between white and black pieces in each subsequent tournament game. But in cricket, the toss can become an all-determining feature and there have been some bizarre sequences, notably earlier this year when Indian captain Shubman Gill lost his sixteenth consecutive toss across all cricket formats, a sequence whose statistical probability is 1 in 65,536. For a while in the late 18th century the code was that the visiting team should always have the choice of whether or not to bat first, and a revival of this practice was mooted at an International Cricket Council meeting in 2018, but the ICC then changed their minds on this, announcing subsequently that the toss would be retained in Test cricket since they declared it was an “integral part” of the sport that also, in interesting phraseology, “forms part of the narrative of the game.”

When cricket began to evolve in the 18th century it was heavily involved with metropolitan centres of gambling, with bookmakers not banned from the Lord’s cricket ground in London until the 1830s. In his book Never a Gentleman’s Game, Malcolm Knox described how cricket between 1870 and 1910 was also riven by gambling and match fixing, with the subsequent Edwardian period, when C.B. Fry’s spirit of gentlemanly amateurism ruled the roost, marking an exception to this general rule.

There have of course been various attempts to marginalize or exclude this emphasis on pure luck, both in the Edwardian emphasis on cricketing morality, where the result was regarded as secondary and the more important aspect was thought to be playing the game in the right spirit according to public school virtues, and also more recently in the contemporary enthusiasm for sports science, which again has sought to minimize the hazards of chance. Figures such as John Buchanan, who coached the Australian men’s team between 1999 and 2007, laid out what Buchanan called “principles for growth” by analyzing statistics and attempting to improve performance outcomes along the lines of corporate managers, by establishing what became known as a “data-driven” approach. Buchanan’s book If Better is Possible draws on the theories of philosopher Edward de Bono to suggest the utility of lateral thinking in approaching cricket questions, and it is interesting that Buchanan and Steve Waugh, then Australian cricket captain, made a point of visiting de Bono during their 2001 Ashes tour to discuss some of his ideas. There are certainly some advantages to this approach, and fielding, for example, is a performance area that has benefitted immensely from more professional input and expertise, something that has paid particular dividends with the advent of television technology to determine very close run out calls. In earlier eras these line decisions would always have gone in the batsman’s favour because such hair’s breadth decisions were rarely accessible to the naked human eye, and so the batsman would have been given the benefit of any doubt. In these pre-television umpire days a run out tended to be an almost comic event involving total miscommunication between the batsmen, like “two clowns in a circus” as Geoffrey Boycott once described on television a run out involving Graham Gooch, and indeed a fielder’s capacity to run someone out with a direct throw on to the stumps was a skill hardly practiced at all.

Nevertheless, this data-driven approach does have its limitations. Nathan Leamon, England’s senior data analyst, acknowledged that in weighing up the respective advantages of having a specialist wicketkeeper who also bats or a specialist batsman who also keeps wicket, it is much more difficult to “quantify” the cost of opportunities missed in the field than the benefits of additional runs scored, with Leamon admitting the price of these missed chances “may well be underestimated.” Somewhat to the frustration of sports scientists, elements not susceptible of managerial control continue to play a significant part in how cricket is conducted. Indeed the former England batsman Ed Smith, who was given out Leg Before Wicket in his last Test match to a ball that replays showed would have been going over the stumps—this was in 2003, five years before the television DRS system was implemented—has written a book about the role and cultural representation of luck in sport and in life more generally, going back through questions of parentage and DNA. The whole idea of luck was antipathetic to Victorian conceptions of meritocracy and the survival of the fittest, when the ultimate triumph of the stronger or more able was regarded as inevitable, but it was also looked down upon by Calvinist notions of providence, the separation of sheep from goats according to the divine will. Cricket structurally combines in compelling ways an intersection of chance and skill, and it is this kind of hybrid condition that is, I would suggest, one of the features distinguishing it from other sports. Arguably, in Ed Smith’s terms, it makes the game more of a reflection of life itself, where elements of randomness and contingency can never quite be excluded.

There have of course always been social conflicts associated with cricket: gentlemen versus players, amateurs versus professionals, Black against White (particularly during the apartheid era in South Africa), and these have been forerunners of current clashes between Anglo-Australian traditions and the new commercial models emerging from India and other parts of Asia. It is, however, one of the characteristics of cricket that it has generally been able to encompass these kind of dialogues within its orbit, and indeed has at times flourished because of them. C.L.R. James said he was convinced that “the clash of race, class and caste did not retard but stimulated West Indian cricket.” Similarly, E. W. Swanton, the crusty doyen of English cricket commentators in the 1960s, deplored in 1962 the loss of amateur status for cricketers and their wholesale incorporation into professional ranks, and he suggested that “the evolution of the game has been stimulated from its beginnings by the fusion of the two strands, each of which had drawn strength and inspiration from the other.” Swanton, like James, saw the tension between these different categories as a positive force, concluding that “English cricket has been at its best when there has been a reasonable even balance.” The academic Stephen Wagg suggested this was simply a cricketing version of the “One Nation” myth, the kind of utopian model advanced by the poet Edmund Blunden in his 1944 book Cricket Country, where Blunden cited approvingly Trevelyan’s argument that “If the French noblesse had been capable of playing cricket with their peasants, their chateaux would never have been burnt.”

This gentlemen/players distinction in England was certainly redundant by 1962, but I suspect the interaction of contrary forces in cricket is somewhat more complicated than Wagg makes out, and I incline more towards Nandy’s view that “cricket is a paradoxical game,” where contradictory forces are brought into dialogue without necessarily being harmoniously integrated or resolved. In Selection Day, in fact, Adiga has a discussion of paradoxography, a scholarly practice common to the Middle Ages that involved the juxtaposition of contraries to support the novel’s suggestion that the intertwining of cricket and corruption is “an old song,” so that, as one of the characters here puts it, “Nothing’s illegal in India . . . Because, technically, everything’s illegal in India.” To put this for a moment in academic terms, cricket might be seen as more dialogical than dialectical, more open-ended than, say, football in its various codes, which involves two teams going full tilt against each other to force a result where one conquers the other, and where there is consequently a dialectical resolution. In cricket, by contrast, the 22 players are never all on the field at the same time, except perhaps during the opening or closing ceremonies, and there is a much greater combination of individual and team skills, involving neither the intense individualism of tennis and golf nor the submersion of individual in the collective that is a requirement in football. It is true that the one-day cricket model, which has become more popular recently, inclines more towards resolution and closure, and Nandy’s observation in 1989 that Indian culture was temperamentally suited to the ambiguities of a drawn match now seems somewhat outdated. Nevertheless, even most one-day matches take longer and involve more discrete modules than other sports—different batsmen and bowlers, sequential innings and so on—and this model of a hybrid interface between individual and collective is inherent in its structure.

Similar dialogical conflicts manifest themselves consistently in the Australian context. In his fine novel The Gift of Speed, published in 2004, Steven Carroll contrasted the slow pace of Melbourne life in the 1960s with the spectre of exhilarating speed introduced by West Indian fast bowlers such as Wes Hall on their 1961 tour. But the especially original aspect of this narrative is the way Carroll uses the metaphor of cricket to signal various interconnections between speed and slowness, using the famous drawn Test at Adelaide during this series, when Ken (“Slasher”) Mackay held out in a last wicket partnership to deny the West Indies victory, as indicative of this kind of symbiosis. “This is not a victory,” says Carroll’s narrator: “It is a draw. Nobody has won and everybody has . . . Everybody, for a short time, has been drawn together by this thing.” One interesting aspect here is the repetition of the draw in cricket in the phrase “has been drawn together”: the model is not of victory but of cohesiveness. This structure of joining things together is endorsed by the rest of Carroll’s novel, which focuses on a multigenerational passage through time, with the grandmother of the adolescent protagonist dying just as he grows up into the adult world. The emphasis is on temporal connection and ritual continuities rather than the slicing of time into market segments.

There has been much discussion in Australia recently of intergenerational equity and how younger generations have been disadvantaged economically by existing social structures, which is I think certainly a fair argument. But the concept of intergenerational equity is not just confined to economic issues and it also extends both ways, backwards as well as forwards. Many people in older generations all across the world have felt culturally displaced by the very rapid changes driven by digital technology and global media since the turn of the 21st century, and one of the most engaging things about cricket, as Carroll’s novel suggests, is that it does not readily accommodate itself to corporate temporalities and technologies, with their built-in obsolescence. The cricket field is characteristically a palimpsestic landscape where past and present exist in a kind of continuum, one often reflected in the architecture of cricket stadiums, not only the famous weathervane of Father Time at Lord’s but also the Georgian pavilion at Sydney, the cathedral overlooking the ground at Adelaide, and in many other venues. Brian Stoddart suggested in 1998 that sport allows more expression of nationalistic fervour than any other human endeavor, and though things have changed since that time with the Make America Great Again movement and so on, the kind of affective attachments and patriotic cathexis that might generally be frowned upon in multicultural liberal democracies is allowed free licence at cricket grounds. Brian Matthews’s autobiography recalls the unreconstructed nationalism informing his childhood in St Kilda in the late 1940s and 1950s, when he played backyard cricket games between Australia and England, and, despite all the market analysts’ attempts to modernize the image of the game, the ways in which these shadows of the past continue to loom over the present constitute one of the game’s most magnetic charms. Again, this is a dialogical principle, what the Russian critic Mikhail Bakhtin described as a carnivalesque mode, where subterranean or nostalgic passions are for a limited time allowed unbridled expression, like the saturnalias in Ancient Rome where masters served their slave for just one day, and which were thought to act as a safety valve that actually served to consolidate existing social arrangements.

I’m quite sure there will be many expressions of nationalist enthusiasm during the forthcoming Ashes series, but equally sure they will be safely contained within the parameters of the event and will not result in open hostilities or armed conflict. Appadurai suggested that in the modern era “cricket teams provide a star-studded simulacrum of warfare on the cricket field,” and of course some of the protagonists and supporters take this martial line to extremes, with Steve Waugh preparing his side for the 2001 Ashes with a visit to the battlefields of Gallipoli, and India versus Pakistan being an especially fraught fixture both politically and religiously, with some spectators known to have committed suicide when the result went the wrong way from their perspective. At the opposite extreme, one-day games can sometimes appear to be pure entertainments, exhibition matches driven by the priorities of television producers rather than the motivation of players or supporters, resulting in an etiolated spectacle that reduces the game to a mere routine, where the performer’s role is “to go exactly through the motions which are expected of him,” as the French critic Roland Barthes said of professional wrestling, rather than engaging in an authentic contest. But in most cases international cricket affords a licence for residual but still active instincts to express themselves, and this is perhaps a dynamic to which politicians in all countries have not paid sufficient respect. We see from the widespread reaction against the technological march of globalization in many countries around the world that it encumbers deep anxieties even among many who accept such progress as inevitable. Stephen Wagg has chronicled how the Blair government in Britain actually produced a policy document entitled “Game Plan,” which advocated an emphasis on what it called “feelgood factors” generated by national sporting successes, something that led to the ubiquitous singing of the hymn “Jerusalem,” a custom that many people found quite tiresome and which I’m sure would have had William Blake, the author of the original poem, turning in his grave. But this self-conscious attempt by Blair to promote an image of national identity through sport as a defensive bulwark against the spectre of globalization is itself telling. For various reasons cricket lends itself well to national iconography, and the multigenerational dimensions of cricket imply significant forms of continuity and cohesiveness across time

There have of course always been conflicts within cricket that have mirrored larger issues within society, and there has been some incisive work on how Indigenous cricketers have been systematically marginalized, despite an Indigenous team being the first Australians to play at Lord’s during a tour of 1868. The academic archaeologist John Mulvaney, who wrote a very good book about this tour, suggested that “if sport is the safety-valve of the people . . . possibly it served a similar cathartic function in racial contact situations,” with the tour producing amicable race relations if meagre profit margins. Labor historian David Sampson, in a more skeptical analysis, suggested that this tour, arranged by White entrepreneurs, was “part of the history of exhibiting colonized indigenous people in England” during the Victorian era, and that it had some parallels with the Buffalo Bill exhibitions around the same time in the United States, where Native Americans were put on commercial display. Women’s cricket has also been largely disregarded by the media until recently, despite dating back to the 18th century and the fact that 24% of all cricket players in Australia are now female. The biography published last year by Bravo Max entitled Alyssa Healy: A Legacy Forged by Courage and Precision offers an interesting account of her life and the challenges facing women’s cricket, but the narrative itself fits rather too easily into the ultimately triumphalist genre that I mentioned earlier, where the model protagonist is represented as overcoming all the odds. It is also I think true that the legacy of Kerry Packer helped to demystify many of the fusty legends associated with cricket traditions, with his unabashed commercialism serving to expose the manifold hypocrisies that for many years masked entrenched self-interest among the game’s ruling elite in all countries.

Bruce Hamilton’s 1946 novel Pro, which is set mainly in the 1920s, chronicles how Edward Lamb follows his father into the county game in England, playing for a fictional country called Midhampton, with the idea among these old pros being that “the world’s work was carried on cricketers, in the same way as it was carried on by engine-drivers, or doctors, or butchers”; but Lamb eventually gets injured and, after a spell umpiring, declines into an impoverished old age. The MCC is represented in this novel as being very suspicious of commercialism since they believe it to be antipathetic to their understanding of the “spirit of the game,” and Lamb, who as a professional cricketer is confined to five months’ seasonal work during the summer, suffers accordingly. I recall an interview with Tony Greig reminiscing shortly before he died about the Packer deal, where Greig recounted how England captain Raymond Illingworth was compelled to work at a Christmas card business during the off season, with Greig saying he was sure Illingworth was very good at it, but it wasn’t a path that he himself intended to follow.

Another very fine cricket novel is the recent Australian work The Rules of Backyard Cricket, published by Jock Serong in 2016. This is set squarely within the contemporary commercial landscape of cricket, where corruption is rife and “the new Professionalism” involves taking advice from media experts on how to cry convincingly during television interviews. The “backyard” cricket here signifies not just the traditional family backyard games played by a pair of cricketing brothers, Darren and Wally, who both go on to play for Australia, but also the hidden worlds of spot-fixing and ball-tampering, as well as what Darren Keefe as narrator claims are the “personal vendettas, lecherousness and racism [that] have simmered away just below the surface of the sport for so long.” Declaring that “Bradman is dead,” along with the “bespectacled gents puffing on pipes” who were the game’s traditional administrators, Darren becomes complicit with the gangster world of Craig Wearne, who deliberately cultivates Darren’s friendship to enhance the effectiveness of his gambling enterprise. Craig says that “sport goes to the heart of everything,” and “if you can reach inside it and mess with its innards, you’re actually messing with society.” This is another way of endorsing the centrality of sport to the broader culture, and it is no coincidence that Serong’s novel cites C.L.R. James’s famous phrase: “What do they know of cricket who only cricket know.” Darren himself is nonchalant about ball-tampering, recalling how his team “were positively encouraged to do it . . . provided we kept it discreet,” and Serong’s book is good at suggesting a yawning chasm between the realities of professional cricket life and its more nebulous forms of mythology. It also sheds an ironic light on the Sandpapergate fiasco that erupted two years later, when several Australian cricketers were caught on camera in South Africa tampering with the ball, and Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull felt obliged to intervene to preserve the national honour.

The best cricket novel of recent times, however, is Chinaman, published in 2011 by the Sri Lankan novelist Shehan Karunatilaka, which was rated by Wisden Cricket Monthly in 2019 as among the top three cricket books of all time, with panel member Tom Holland, the History Podcast man, saying how it shows “that cricket can become the stuff of remarkable fiction,” hence “transcending the genre in which it exists.” The book is organized around a journalist’s investigation into the life of Pradeep Mathew, who is actually a fictional character, though many of the incidents in the book are taken from real life. This includes the title “Chinaman,” a reference to a top-spinner delivered by a left-arm bowler, with the name of the delivery deriving from an incident during a 1933 Test Match between England and the West Indies, when after being dismissed by Ellis Achong—who was a Trinidadian bowler of Chinese descent—the English cricketer Walter Robins exclaimed: “Fancy being done by a bloody Chinaman.” The mystery spin of this chinaman, which is said to be Pradeep Mathew’s stock ball, is correlated here with the formal oscillation between fact and fiction in Karunatilaka’s narrative, its tendency to spin and swing both ways, and this in turn is associated with Sri Lanka’s cultural production of freaks—white elephants, golden frogs, blue leopards. This twisting of fact into fiction is also linked to Sri Lanka’s reversal of Western hegemony: the drunken narrator W.G., himself an ironic mirror of Victorian cricketing legend W. G. Grace, says: “This is not Lord’s or the MCC. This is urchin cricket played on the streets of Mariyakade or de Saram Road. The Poms were finally playing it Lankan style.” There are references here to Salman Rushdie, whose literary idiom of magical realism the book resembles, and also to cricketing and political hostilities between Sri Lanka and Australia: “The reason we hate the Aussies,” says W.G., “is because of their umpires no-balling Murali [that’s Muralitharan, a famous real-life Sri Lankan spin bowler], their bowlers calling our batsmen black monkeys, and their press calling us cheats. But most of all because they’re tougher, better organized and impossible to beat.” The book is remarkable not only for its comic encompassing of Sri Lankan history—“When the game was first introduced in the colonies, two centuries ago,” it says, “the fat masters batted all day, while the emaciated slaves bowled”—but also for its aesthetic capacity to mix things up. The novel depicts how “in sport, politics and everything else, Sri Lankans tend to veer between jungle law and Victorian morality.” The team ethic is said to be subservient to the quest for money and individual glory, as W.G. records acerbically “a prominent Sri Lankan batsman boasting in the comfort of the dressing room that he only does his best when there’s a car offered for the man of the Match,” adding that he “has over forty such awards in his career.” In this sense, it comically represents how cricket is embedded in the new Sri Lankan culture, while also using the discursive field of cricket to open up wider questions about the boundaries of contemporary social life.

Pradeep Mathew in Chinaman is said to bowl “a perfect googly,” the ball which seems to be spinning in one direction but then reverses its trajectory, and the fact that he can bowl both right-arm and left-arm underlines his ambidextrous qualities. Gideon has discussed in his book Sphere of Influence how the googly has a somewhat shadowy history within the annals of cricket, with its (quote) “double-dealing nature” being “in some quarters regarded as unethical,” and Joyce typically uses the googly in Finnegans Wake to suggest the intersection of contraries: “We’re parring all Oogster till the empyseas run googlie.” Oogster here puns on oldster, with Thomas Parr being a legendary Englishman said to have sired a child when over 100 years old, and this figure being conjoined with parr as newborn salmon returning to the empty sea after the oldster has died of spawning. Hence googlie in the middle of this paragraph replete with cricketing references evokes for Joyce the double movement and recursive intersection of death and life, just as the book’s title turns on the larger cycle of finishing and reawakening: Finn/again/wake. The American novelist Thomas Pynchon also deploys the figure of the googly in his 2006 novel Against the Day, where Pynchon seeks to reimagine time and space through an idiom of reversal. To project a shift of the United States into what the book calls “planet-shaped consciousness,” one of the characters suggests that England will only regain the upper hand in their cricket encounters with Australia “if they’ve the sense to select this Middlesex spinner, young Bosanquet, who’s been working on an absolutely fiendish ball, which looks as if it will be a leg break but then goes the other way. Amazing physical dynamics, virtually uninvestigated. Said to be an Australian invention, but they’ll be utterly confounded at finding a Pom who knows how to bowl it.” The word googly is said to be of Maōri origin, first used in New Zealand in 1903 to suggest uncanny, weird or ghostly, and it is no surprise to find Pynchon here drawing on this antipodean oddity to throw a spoke in the wheel of American corporate systems.

This again suggests that cricket is the province of many distinguished writers and intellectuals, as well as larger audiences in countries where it is played, and that it should not be seen as merely the plaything of imperial loyalists. Thomas Paine, who was as iconoclastic a character as ever lived, attended the Hambledon Cricket Club’s dinner in 1794 as the guest of radical Whig Henry Bonham, while Samuel Beckett, who played two first-class games for Dublin University against Northamptonshire in 1925 and 1926, was in his later years, long after Waiting for Godot had made him famous, an avid follower of cricket and rugby on television. Harold Pinter, a friend of Beckett who was active in radical politics, also delighted in playing and watching cricket, which he described as a “very violent game, however friendly it may seem.” That might seem like a summation of Pinter’s own plays, of course, though it is not difficult to see how it applies also to the world of cricket, particularly after the accidental death of Philip Hughes, and it also testifies to the game’s inherently chameleonic tendencies, how observers tend to read into it what they want to find. But this open-endedness is, I think, a structural element within the internal constitution of cricket. As many commentators have suggested, the variety of the game, or what Marqusee called its “multiform, polysemous nature,” is part of its distinctiveness, and in that sense current controversies about the virtues of test match as opposed to one-day cricket, or about the rising influence of India on the world game, are in many ways heirs to older debates about gentlemen versus players or professional commerce versus amateur virtue, and they are the kind of oppositions and contradictions that cricket can not only tolerate but also embrace creatively. C.L.R. James, though an important campaigner against racism in Caribbean cricket, also admitted to liking the cricket novels written by the extremely conservative P. G. Wodehouse, his 1909 Mike and so on, and this I think exemplifies the multidimensional nature of cultural allegiances as well as human psychology, and how reductive it can be to reduce everything to the salami slices of social media cohorts, where all positions tend to be marked out and circumscribed in advance.

In this sense, the googly or topspinner, the ball that veers in opposite directions, might perhaps crystallize the spirit of cricket more than the vague edicts periodically issued by the ICC and other administrative bodies. Shane Warne was not so much a purveyor of googlies as sliders, but he was a prodigious spinner of the ball and a master of the unexpected, and his so-called “ball of the century,” the first ball he bowled in a Test match in England with which he dismissed Mike Gatting, has been much the subject of many retrospective interviews and documentaries. However, what seems to me particularly interesting about it is not so much the delivery itself but the narratives around it, the way in which the event was represented. BBC Radio’s Test Match Special commentary is particularly revealing, with Jonathan Agnew talking to Trevor Bailey, the old Essex and England seamer who was an epitome of 1950s cricket conventions, both socially and professionally. When he sees Warne is coming on to bowl, Bailey makes disparaging remarks about his bleached blonde hair as well as the number of runs he had conceded in the previous Test series in India, and they both agree the England batsmen are going to enjoy themselves. After Warne has wreaked his magic they can’t quite fathom out what has happened, and the subversion of their normative expectations is a mirror in media terms of Warne’s disruptive spin. The television commentary in this case is not so effective, with Richie Benaud’s famous stylistic minimalism for once not doing justice to the sense of astonishment that was the key feature here (Benaud just says “he’s done it”). Benaud himself was of course one of the important figures in Warne’s professional development, encouraging him to integrate his exceptional talent with an equally remarkable sense of accuracy and self-discipline, and both of these attributes come into play here, as indeed they did throughout the rest of Warne’s heterodox career. Such openness to heterodoxy and to an interweaving of different strands is, I would argue, a facet linked not merely to any individual cricketing genius but an aspect woven inherently into the game’s multidimensional narratives. Thank you.

Works Cited

Adiga, Aravaind. The White Tiger. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2008.

----------. Selection Day. London: Picador, 2016.

Appadurai, Arjun. “Playing with Modernity: The Decolonization of Indian Cricket.” In Carol A. Breckenridge, ed., Consuming Modernity: Public Culture in a South Asian World. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995, 23-48.

Bakhtin, M. M. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Trans. Caryl Emerson. Ed. Michael Holquist. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1982.

Barthes, Roland. “The World of Wrestling.” 1957. In Mythologies. Trans. Annette Lavers. London: Jonathan Cape, 1972, 15-25.

Beckett, Samuel. Waiting for Godot. Paris: Editions de Minuit, 1952.

Blunden, Edmund. Cricket Country. London: Collins, 1944.

Buchanan, John. If Better is Possible: The Winning Strategies from Australia’s Most Successful Cricket Team. Prahran, VIC: Hardie Grant, 2007.

Carroll, Steven. The Gift of Speed. Sydney: HarperCollins, 2004.

De Bono, Edward. Lateral Thinking: A Textbook of Creativity. 1970. Rpt. London: Penguin, 1990.

Gupta, Amit. “The Globalization of Cricket: The Rise of the Non-West.” International Journal of the History of Sport 21.2 (March 2004): 257-76.

Haigh, Gideon. Sphere of Influence: Writings on Cricket and its Discontents. Melbourne: Victory Books, 2010.

----------. On Warne. Melbourne: Hamish Hamilton, 2012.

Hamilton, Bruce. Pro. London: Cresset Press, 1946.

Ismail, Qadri. “Batting against the Break: On Cricket, Nationalism, and the Swashbuckling Sri Lankans.” Social Text No. 50 (Spring 1997): 33-56.

James, C. L. R. Beyond a Boundary. 1963. Rpt. London: Serpent’s Tail, 1996.

Joyce, James. Finnegans Wake. London: Faber, 1939.

Karunatilaka, Shehan. Chinaman. London: Jonathan Cape, 2011.

Knox, Malcolm. Never a Gentleman’s Game: Blood, Boycotts and Bullyboys. Melbourne: Hardie Grant, 2012.

Mandle, W. F. “Cricket and Australian Nationalism in the Nineteenth Century.” Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society 59.4 (Dec. 1973): 225-46.

Marqusee, Mike. Anyone But England: An Outsider Looks at English Cricket. London: Verso, 1994.

Matthews, Brian. A Fine and Private Place: A Memoir. Sydney: Pan Macmillan, 2000.

----------. Benaud: An Appreciation. Melbourne: Text Publishing, 2016.

Max, Bravo J. Alyssa Healy: A Legacy Forged by Courage and Precision. YellowMonkey, 2024.

McGrath. Test of Will: What I’ve Learned from Cricket and Life. Sydney: Allen and Unwin, 2015.

Mulvaney, John, and Rex Harcourt. Cricket Walkabout: The Australian Aborigines in England. Melbourne: Macmillan, 1988.

Nandy, Ashis. The Tao of Cricket: On Games of Destiny and Destiny of Games. 1989. Rpt. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Pynchon, Thomas. Against the Day. New York: Random House, 2006.

Ryan, Christian. Golden Boy: Kim Hughes and the Bad Old Days of Australian Cricket. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen and Unwin, 2009.

Rushdie. Salman. The Moor’s Last Sigh. London: Jonathan Cape, 1995.

Said, Edward. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books, 1978.

Sampson, David. “‘The Nature and Effects Thereof Were . . . by Each of Them Understood’” Aborigines, Agency, Law and Power in the 1867 Gurnett Contract.” Labour History No. 74 (May 1998): 54-69.

Serong, Jock. The Rules of Backyard Cricket. Melbourne: Text Publishing, 2016.

Wagg, Stephen. Cricket: A Political History of the Global Game, 1945-2017. London: Routledge 2017.

----------, ed. Cricket and National Identity in the Postcolonial Age: Following On. London: Routledge, 2005.

Smith, Ed. Luck: A Fresh Look at Fortune. London: Bloomsbury, 2012.

Stoddart, Brian, and Keith A. P. Sandiford. The Imperial Game: Cricket, Culture and Society. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998.

Wallace, David Foster. “Tennis Player Michael Joyce’s Professional Artistry as a Paradigm of Certain Stuff about Choice, Freedom, Discipline, Joy, Grotesquerie, and Human Completeness.” 1995. In A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again: Essays and Arguments. New York: Little Brown, 1997. 213-255.

Warner, Marina. “My Grandfather, Plum.” Guardian, 11 June 2004. Online.

----------. “Magical Aesthetics.” In Christian Thompson, Ritual Intimacy. East Caulfield, VIC: Monash University Museum of Art, 2017. 63-76.

Wigmore, Tim. Test Cricket: A History. London: Quercus, 2023.

Wodehouse, P. G. Mike. London: Adam and Charles Black, 1909.

Again, thanks to Paul for the invitation to participate and permission to reprint. Tomorrow, as mentioned, a response in which I pick up some of Paul’s lines of thought.

This is a wonderful essay from Paul. Very enjoyable to read, and full of insights which is typical of Paul’s writing. A couple of novels not mentioned that have strong cricket elements are Malcolm Knox’s A Private Man and Joseph O’Neill’s Netherland. Both novels are good reads and I would be interested to get Paul’s take on them (or Gideon’s or Pete’s). Joseph O’Neill’s most recent novel Godwin about recruiting footballers from Africa is superb and possibly my favourite novel that centres sport at the heart of the book. What other “cricket” novels are out there that people would recommend?

A song to accompany your response, Gideon: https://music.youtube.com/watch?v=UC6qFtOg5O4&si=BqGP81ElECSkueXk