Lane of Dreams

GH on a sacred cricket spot

Melbourne is famous for its laneways. Artists turn them into hotspots. Music fans make them places of pilgrimage. But this unnamed laneway, as it appeared in 1950, should I think be the most famous of all.

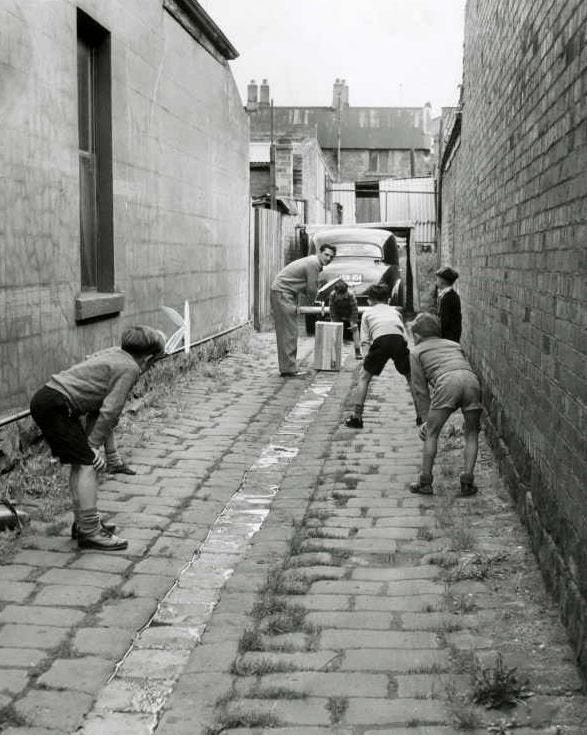

Why? Because cricketers. The house on the left was occupied by Horace Harvey, nightwatchman for the nearby McRobertson confectionery collosus, his wife Elsie and their seven children - daughter Rita, and brothers Clarence (Mick), Harold, Merv, Ray, Neil and Brian. Below is Neil, greatest of them all, paying a reminiscent visit to the space in which he and his kin learned the game in the 1930s and 1940s.

Of the house at 198 Argyle Street (here’s Brian, Horace and Elsie)…

…this is all that survives.

But the laneway, which dates roughly to the turn of the twentieth century, has miraculously outlasted the relentless march of gentrification, and now looks like this.

The toilet on a length is temporary, and relates to the massive earthworks for a looming block of apartments - at least I did not have to give directions to the facilities as seventy Harvey family members, Cricket Et Al subscribers and friends came together at noon today to commemorate what I would argue is Australian sport’s most historic improvised space.

Yes, that’s Brownlow Medallist Robert Harvey, Neil’s grand nephew. Also Beth Mooney….

…who was a guest of Kirby Short, Neil’s grandniece, here with Neil’s son Bruce.

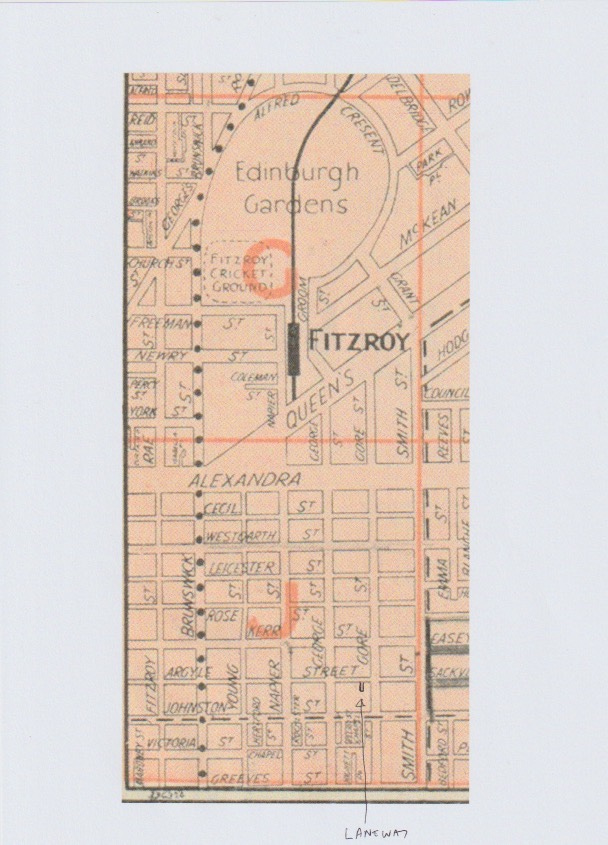

The lane, set among the tiny houses and factory smokestacks of working-class Fitzroy, was so small it eluded contemporary street directories….

….but became a source of great local pride.

In November 1950, the storied journalist Hugh Buggy threaded his way through the suburban backstreets asking his way to the Harvey household, and found it deceptively easy, for ‘the whole sweep of North Fitzroy is Harvey country.’

All North Fitzroy knows and respects the Harveys. Everyone there takes pride in the fact that this intensely Australian family in Argyle Street has given North Fitzroy its first young Test cricketer of infinite promise. They are proud also of the fact that Neil Harvey, without influence, without pull of any kind, but by sheer cricket ability, has attained to the emerald green blazer of the Australian eleven. For a youth living, so to speak, around the corner to climb to the heights of Test cricket is for them a triumph for democratic North Fitzroy. They see Neil Harvey, a rather serious minded, dark haired, local boy, hurrying off in the morning to his job as an electrical fitter. Many of them recall him as a small boy hurrying off to school with an Eton collar and a big bow. They remember the same little boy smiting a ball into their backyard or on to the roof of the woodshed. They even admired the way he defended his kerosene tin wicket against long hops, half volleys, and balls that turned mischievously on loose road metal.

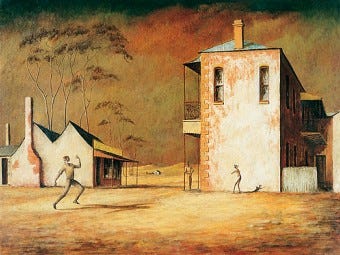

This intensely Australian family. I love that. It was two years since Russell Drysdale had rendered The Cricketers (1948) - that paradigmatic image of Australian cricket in its raw, untutored and uninhibited state.

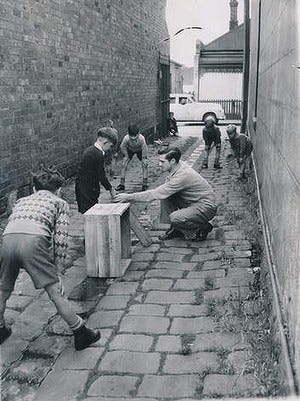

Buggy dwelt on how the Harvey boys had adapted and condensed the scene for an urban setting, delineating in detail the rules of the four-a-side games played by the Harvey brothers with their friends, scored in chalk on the wall of their home.

They had a bat, but no stumps. Anyway they couldn't have set up stumps on the jagged bluestone surface of the lane if they had them. A deal box served as a wicket.

Mrs. Harvey ruled that a tennis ball only could be used if all the windows in the congested neighborhood were not to be broken. There, in that lane, on Saturdays, and after he and his brothers had returned from Sunday school, Neil Harvey learned the rudiments of batting.

He learned them the hard way. On the irregular bluestone chunks of "the pitch" the tennis ball cavorted and caracoled and turned handsprings. Its gyrations were hard enough for "the batsmen" to follow at the best of times; but the boys framed almost Draconian rules that made their game even harder.

If the ball was hit against the wall of either house and caught on the rebound by bowler or fielder, the batsman was out. If it was lofted into an adjacent backyard, he was also out. That lane is just wide enough for a car to glide through, so these rules encouraged the straight drive.

Hooks or cuts were risky, as the ball inevitably had to rebound from one or the other wall. A drive as far as the gutter bordering the south footpath was worth two runs. If the ball hurtled to the fences of houses on the north side of Argyle street it was a boundary shot worth four. In this lane cricket the embryo Test batsman was certainly cribbed, cabined, and confined.

A fielder was not allowed to field in Argyle Street, where he could cut off most of the fours. He had to post himself inside the mouth of the lane. This close field meant that the boy batting had to belt the ball hard to beat the lane fielders by sheer pace.

We know that Neil Harvey now plays even defensive shots so hard that they race to bowler or fielders like a bullet. It is interesting to speculate whether his lusty straight and on driving is in part a legacy of that confined lane cricket, when the ball had to be hit hard to score at all….

When the boys outgrew their lane, moreover, there was a cricket club in the vicinity. It would have been a tram down Brunswick Street or a walk down Gore Street to Fitzroy CC, which since its foundation in the 1860s had been located in Edinburgh Gardens. Neil started in the fifths there in 1940; within four years, aged fifteen, he was in the firsts.

Four years later, of course, he was among Bradman’s Invincibles (here he is with his brothers on returning, flanked by Rita and Elsie).

Today, aged ninety-six, he is the last of them, but he sent us a brilliant message via Bruce: ‘We didn’t think we had any ‘stars’ in our family, it was just us, and we had fun.’ Nephew Graham then talked about the generations of family sporting prowess that essentially emanated from his laneway. Though Fitzroy CC have long since merged and moved, current tenant Edinburgh CC were kind enough to open their rooms to felicitate the Harveys, who had come from as far away as Christchurch, Brisbane and Adelaide. We learned that Edinburgh unconsciously play for their own version of the Ashes - Merv’s were scattered there.

The plaque we foreshadowed today is a downpayment on an on-going preservation effort that Cricket Et Al kicked off last November. The images, I think, tell a tale. In 1950, because Neil still lived at home, he was readily available to help Buggy’s photographer get the images right, and for the local kids to play their part in a reeactment.

But the more significant presence was the car seen at the top, even then turning the lane into an ersatz driveway. Fitzroy was assimilating traffic. Cars were displacing kids. Google Maps, in fact, shows the lane as a sneaky car park.

Today, however, the girls from Edinburgh CC helped us claw the laneway back for cricket.

And having made our territorial claim, we plan to push for the cobbles to be officially designated Harvey Lane, in commemoration of the family’s epic contribution to Australian sport. The lane, I think, is not only a time capsule from a day when the streets were also community space, but evokes cricket’s abiding eye - that instinct, when presented with a spare bit of room, to start playing, to make rules on the run, to keep on til it’s dark. Long may it flourish.

What a great article and piece of writing GH.

I wish my father was alive to read this - his favourite batsman was Neil Harvey and he and my Mother would sit in the Sheridan Stand at the SCG in the late 1950s/early 1960s and watch him and others play.

I don't know if this is true but Dad claimed at the end of the day he would come up and have a chat with my parents and his parents who would often sit in the same stand - even if it isn't true I would like to think it is - a great story regardless.

I did get to sit in the Sheridan Stand as a kid in the early 1980s before it was demolished to build the Clive Churchill stand.

Thanks as always for the wonderful prose.

My mother grew up in Fitzroy with 4 brothers who all knew and played in the lane way with the Harvey’s.

She lived nearby in Napier st.

She always pronounced Napier as “Na peer” and refused any other pronunciation

Great pictures