No use crying over spilt ink: how an accident in an art exam led to a remarkable career

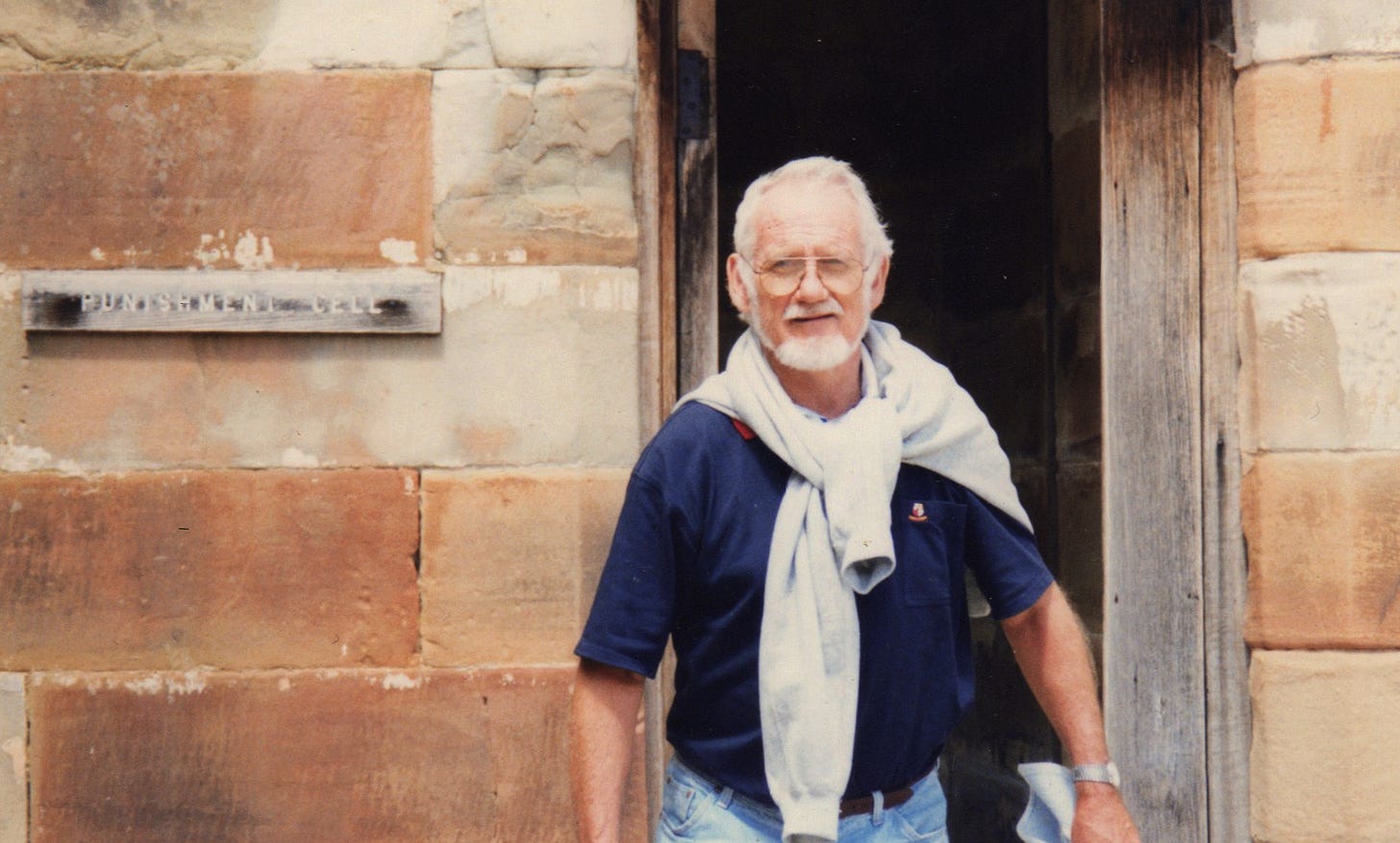

PL on Lost Landscapes, a major retrospective of his father in law Gordon Rintoul's work

Cricket Et Al is heading to Singleton in country NSW to attend a retrospective art show that’s close to home.

For years, Sue has been wrestling with the legacy of her late father’s extraordinary art career, and all that work is finally coming to fruition as almost 40 canvases are ready to be loaded into a truck and delivered to the Singleton Arts and Cultural Centre this week.

Gordon Rintoul, her father, worked as an artist in New York, Newcastle and Sydney, but it was the beauty and intersection of landscape and industry in NSW’s Hunter Valley that were almost a lifelong inspiration.

Lost Landscapes by Gordon Rintoul will open on 6 Feb and show until 3 May. It’s the endpoint to some degree of an unlikely journey that began 80 years ago in country NSW, where my father-in-law-to-be was a well-known sportsman who played in the firsts for the successful local league team. He would go on to be a state basketball coach and a lifetime devotee of Manly Sea Eagles.

He had, despite the athletic pedigree and surroundings, been moved by a small surrealist print that had somehow found its way onto the library wall of Young High School in the 1940s. Gordon wrote later that he was “fascinated and engrossed by this Salvador Dali. Dreams of the impossible were made visible. It gave me an open window to an entirely imaginative world.”

Long before television, the internet, or social media, somebody, possibly a teacher like Gordon, thought to frame and hang a work by the pioneering Spanish surrealist on the wall of a country high school in Australia.

Gordon didn’t want to follow the path of the men in his family who were builders or the kids at his school who were set to do what the young men of Young always had. He resolved to find a career in art, and in November 1947, he attended the school’s Assembly Hall to sit a two-hour practical art examination for a teaching scholarship that called for students to complete a human image task.

He was confident, and after 90 minutes had finished something he was happy with, believing he’d “done very well indeed. I thought I had produced a slowly, deliberately and plausible illustration, even slightly heroic in its way. I sighed with relief, satisfied, and pleased with myself”.

And then disaster struck.

Reaching for something, the aspiring artist’s elbow knocked over a bottle of black Indian ink that spilled across the finished drawing. Gordon recovered from his initial shock, sucked it up and decided he’d just have to do his best to approximate something in the 30 minutes remaining.

I rallied, realising there was nothing else I could do. I drew yet again, this time on a fresh sheet of white cartridge paper. Time was against me it would be impossible to duplicate the carefully constructed, detailed study again.

Fortunately, the composition and the problem of integrating depiction and creation simultaneously were behind me. I had a template to follow.

More urgent and spontaneous marks appeared by necessity with many details left out in the editing process.

I rationalised that the viewer would just have to complete the ideas in their own heads.

Somehow, this gave the new work an unintended strength and life of its own. I had changed the process and a change in the outcome followed.

Helping Sue with the body of work that is her father’s legacy, I kept thinking about this moment almost 80 years ago. Had he thrown his hands in the air and quit, what would have become of his life? Had necessity not forced him to work a certain way in those 30 minutes, would his art have taken a different course?

Going through the paintings in his studio on Lake Macquarie, as we have been lately, I’m glad he stuck with art, and I suspect nothing would have stopped him. Gordon was driven. Almost obsessive. As all dedicated artists have to be. Completing that exam, getting the scholarship and a place in the course he wanted was the first step toward a life that saw him living and working in a world that became him.

In the early 1980s, he took his wife Coral and family to upstate New York, where he embarked on a set of epic paintings, an American flag series, that are my favourite and one of which is on the wall of our lounge room.

This was his explanation of the works:

In the early 1980s America was consumed with fervour and frustration in the Iranian hostage crisis. Flags were everywhere. As part of my MFA program, research of contemporary art in the great museums of North-Eastern America was occuring and these two experiences fused.

I speculated how selected artists would paint the US flag today, (chosen on an homage basis) and the final presentation is intended to parody nationalism.

Gordon’s landscapes are where his interests, talent and circumstance are given their fullest expression. Informed by his asthma and a life in the Hunter Valley, where BHP’s Newcastle steelworks and the coal mines were the main employers, he was fascinated by the intersection of industry and the environment long before they became mainstream topics.

Curator Christopher Dewar noted this in his introduction to the retrospective.

In a time when the global conversation around environmental collapse, cultural identity, and political polarisation feels more urgent than ever, it is both timely and necessary to revisit the work of Gordon Rintoul. Since the 1960s, Rintoul’s work had already been grappling with themes that now dominate our headlines: environmental toxicity, nationalism, and the consequences of unchecked industrialisation. His work found its voice in the 1970s and 80s, decades marked by fears of acid rain, nuclear fallout, and the Cold War.

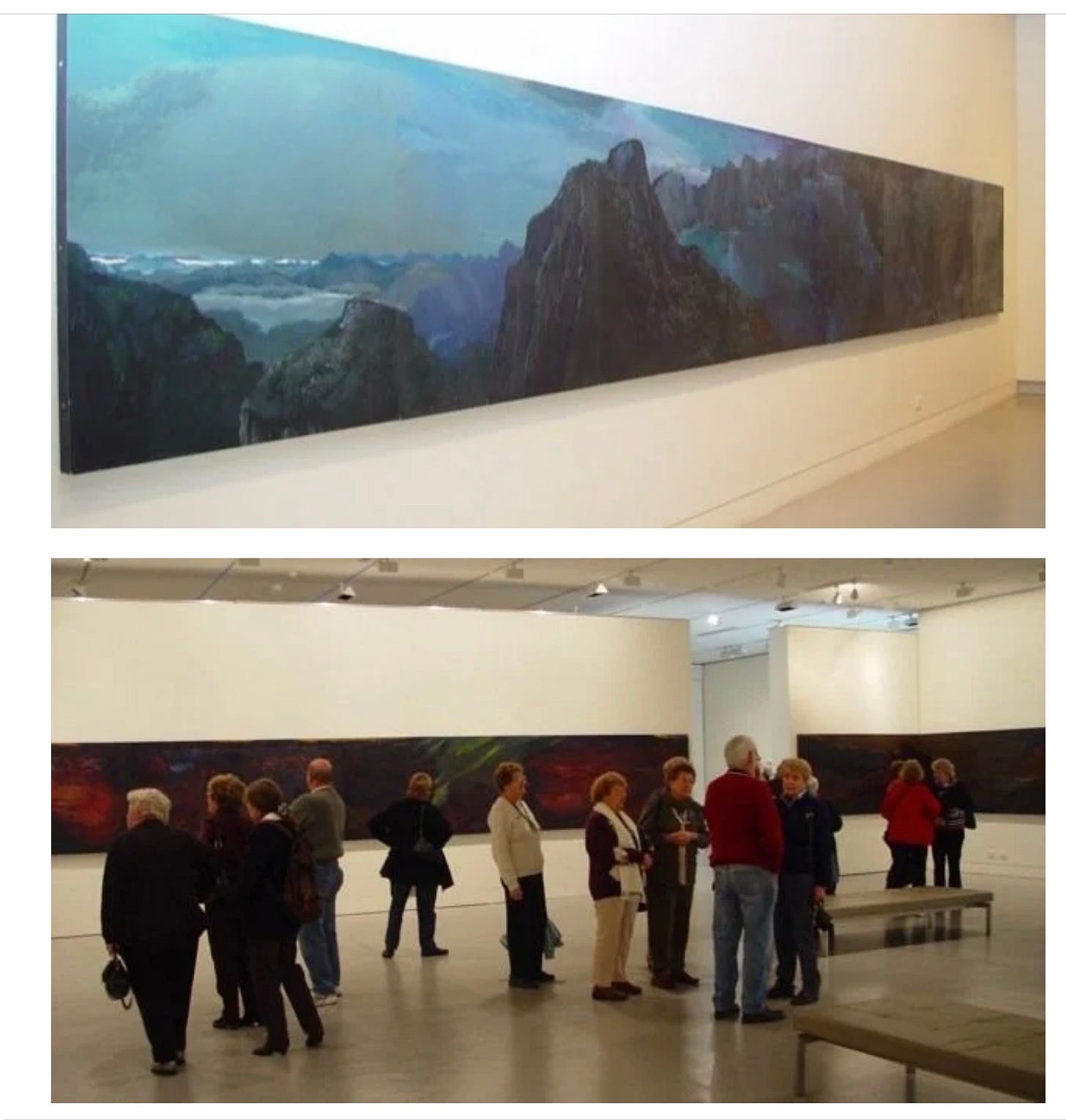

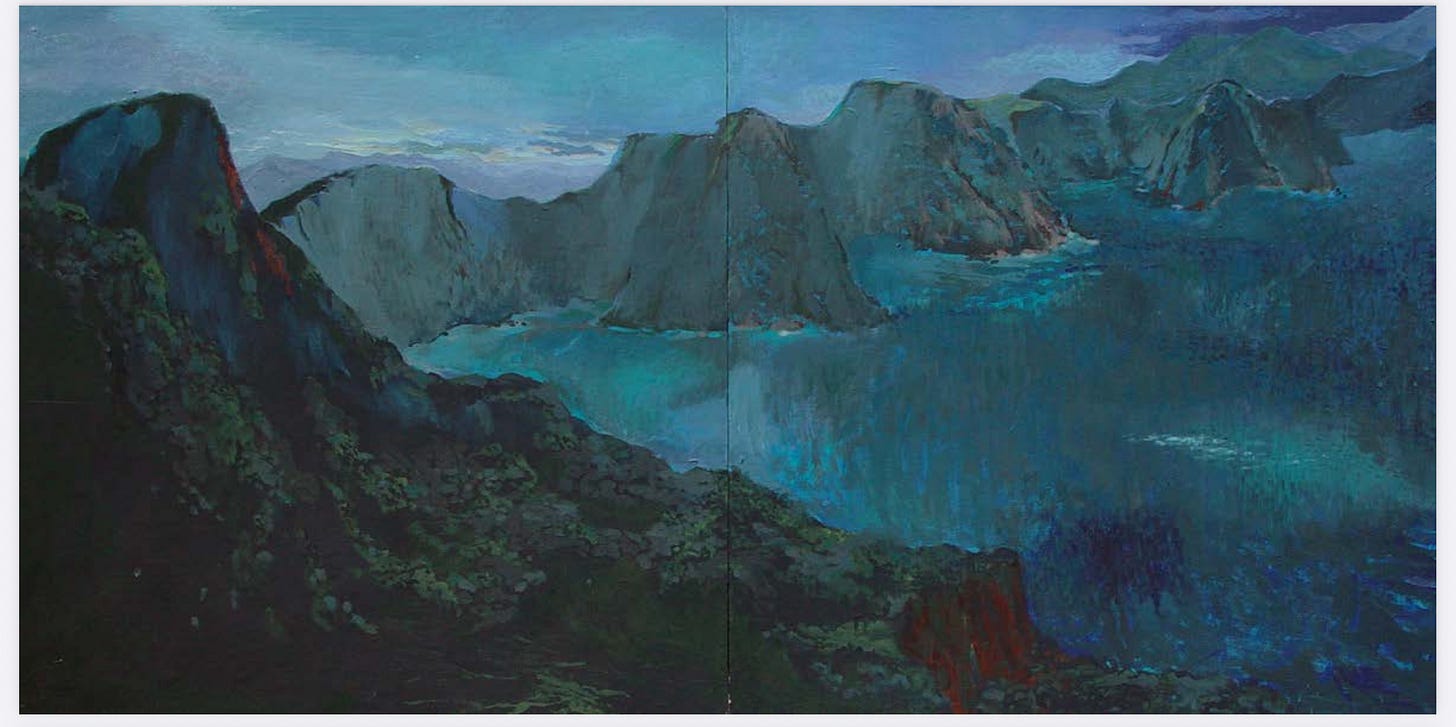

This area of work culminated in a series called Lamentations for Lost Landscapes, which he completed as part of his PhD thesis in the 1990s. The panoramic multi-panel landscape stretches for 48 metres over 40 panels and was inspired by a pivotal visit to Queenstown in Tasmania in the mid 1960’s, where mining had wrought so much damage to the once pristine wilderness.

This is two panels from the work:

And this is a detail from a section in the Tweed Regional Gallery in 2007.

There is, however, a film on Youtube which shows the entire work.

Gallery Director Courtney Wagner wrote in her foreword that the Lost Landscapes retrospective:

invites considered reflection on place, memory and change … This exhibition is also a reflection on the role of painting as a form of inquiry, as we encounter surfaces that are buit, reworked and unsettled, mirroring the landscapes they evoke.

Gordon’s paintings were always a work in progress. Going through the canvasses you can see hints of the re-workings and adjustments he made to them over the decades. Wagner notes:

Lost Landscapes holds particular significance for Singleton and the Hunter Region, as Rintoul lived and worked here for many years and contributed profoundly to the cultural life of the region as both an artist and educator. The Hunter’s landscapes, marked by industry, extraction, resilience and regeneration, provided ongoing stimulus for his practice.

Gordon was an artist who constantly experimented with different media, which gives the works a textural, lively and almost sculptural feel. He even, I’m told, used cooked spaghetti in some works. He was involved in over 50 exhibitions in his lifetime, but nothing on the scale of this retrospective about to open in Singleton.

Gordon studied art in Sydney before moving to the Newcastle region in the 1970s, where he lectured in painting at the University of Newcastle. He was a passionate educator who said that his more fulfilling work came later when he taught in the University’s Open Foundation program, where he mentored hundreds of mature-age applicants preparing to enter visual arts study.

Anyway, the show runs from 6 February as previously stated, and if you are in the area and want to come to the opening, it would be good to catch up. Gideon is coming up and is keen to record a podcast in Singleton. I guess we can talk about pictures and pitches, pictures of pitches, that kinda stuff. Most of the works are for sale, but this is not a commercial exercise. While it is going to be hard for the family to let them go, they deserve to find a place out there among the community, and this was one way to do it.

I’m excited about getting the chance to see paintings I’ve only ever known up close and personal, from a distance on big walls as they were meant to be seen.

Some more of his works can be found here, a website Sue built some years ago when she started this project, which is about to come to fruition.

I grew up near Windsor and my old man built and maintained the bridges on the Putty Rd. I sense a road trip coming on. Good luck managing such a legacy of work.

The Lost Landscapes cover image, Pete, is both RICH (plum pudd or fruit cake maybe) and HAUNTING. Talking to a guy like Doug about his interpretations would have been fascinating. There is something Orwellian about his work. Nice piece.