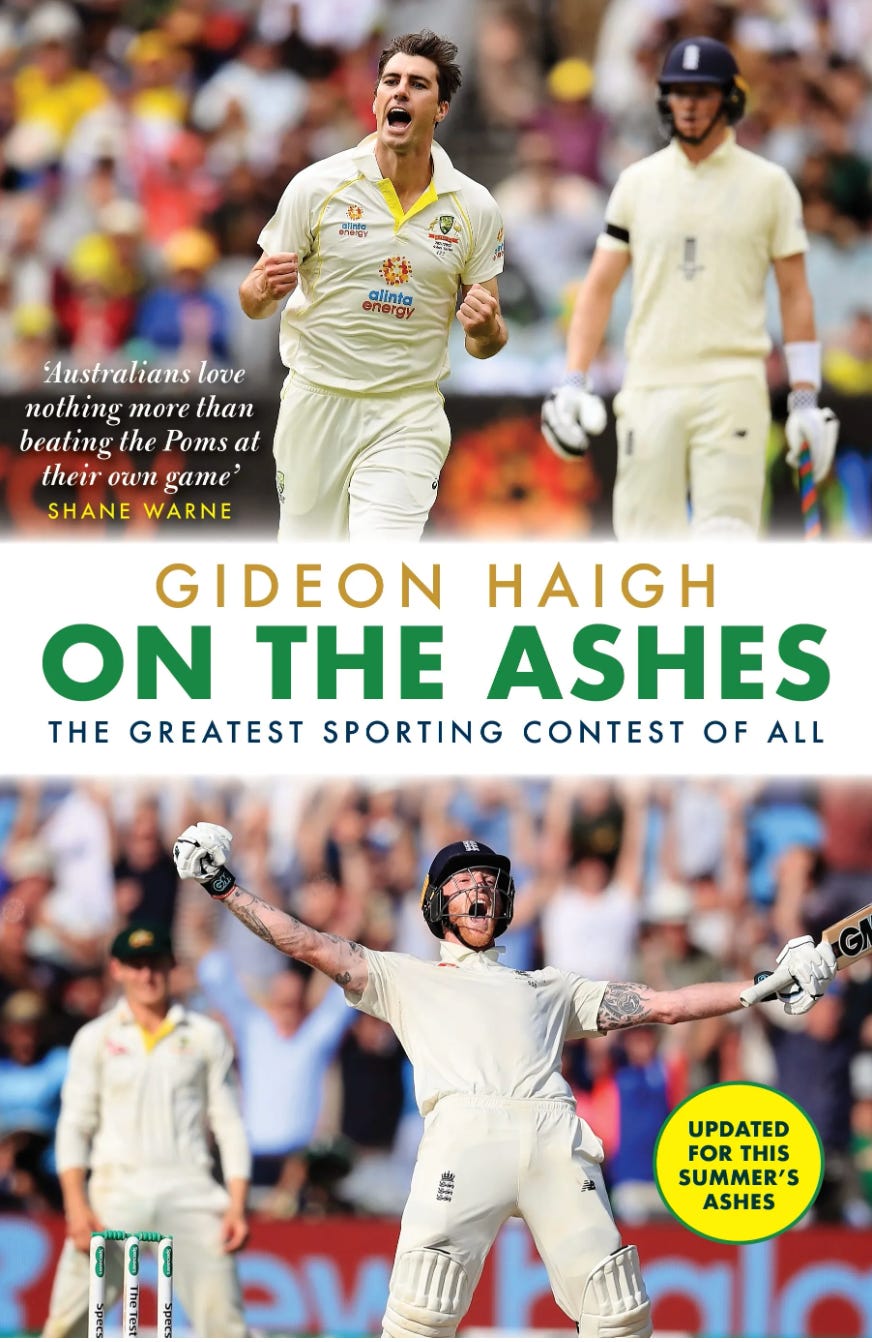

Out Now: Raking Over the Ashes

GH with one prepared earlier

Have we told you that the Ashes is on this summer? This may have something to do with a new edition of On The Ashes, available in Australia and England, updated for the series of 2023. Here’s an extract as a Sunday read - one of the (many) pieces I wrote on the death of Shane Warne, which seems in a way very recent, such is the sunny freshness of his memory, and long ago, such is cricket’s rapidity of change. It starts with one of my favourite Warne stories - apologies for the language. GH

On the evening of 3 June 1993, the Carbine Club, a social club bonded by ‘sport, fellowship and the community’, gathered at the Melbourne Cricket Ground for its annual dinner. Its guest speaker was Terry Jenner, cricketer turned coach, recently identified with Shane Warne, rising Australian leg-spinner. As the evening flashed by, a television at the back of the room tuned to Channel 9 began screening the First Test of the new Ashes from Old Trafford; as the evening neared its end, it happened that a club member was standing beside Jenner as his protege took the ball for the first time.

This part of the story we know: after first veering to leg, Warne’s leg-spinner reversed course and cuffed off stump, leaving Mike Gatting between wind and water, and the world agog. The reaction at the MCG? ‘You cunt!’ swore Jenner. ‘You fucking little cunt!’ The club member, who recently told me this story, couldn’t believe what he was hearing. ‘But Terry,’ he pointed out. ‘That ball…..’

Jenner’s face broke into a smile. The day before, he explained, he had had a long conversation with Warne about how to approach his initial overs against England. Nothing special, they agreed. Feel your way into the contest. Just be patient. Well, so much for that: Warne, he had decided, was the contest, and he would not wait. As he later transcribed his interior monologue: ‘You gotta go. Come on, go, mate, pull the trigger, let’s rip this.’

Thirty years on, Warne is gone, but his signature feat and its impact abide. One of the most remarkable features of the Ball of the Century is that nobody had imagined such a thing until it happened. We were ninety-three years into the twentieth century before it was proposed that a single delivery could so stand out from everything before it. Baseball had its Shot Heard Round the World. Football had its Hand of God. But cricket had never so isolated, analysed, celebrated, and fetishised a single moment. Here was the mother of all highlights, ahead of a boom in the concept, expedited by a format, T20, geared to their mass manufacture

Simultaneously leaning against that trend towards commodification, however, was also Warne, who never bowled a ball without expecting to appeal, who was always scorning the ordinary in quest of the extraordinary, who was always reminding us that we love cricket because we do not know what will happen rather than because we wish for an orderly procession of familiar events.

Nobody saw Warne coming; nobody has replaced him since he retired. He benefited, to be sure, by the Australian initiative of a cricket academy in Adelaide, which is where he first encountered Jenner. Yet Warne was there only because his preferred career as an Australian rules footballer in Melbourne had petered out, and he was rejected at first for his youthful wildness. ‘Cricket found me,’ he was wont to say, which was not quite accurate, but as an idea uplifting.

The balance of Warne’s career, in some ways, had to contour itself to the template of that first ball he bowled in an Ashes Test. In the aftermath of his death, highlights reel after highlights reel was presented for our delectation, offering variations on the same theme. Warne’s inimitable pause at the end of his run; Warne’s seemingly artless approach; Warne’s hugely powerful surge through the crease, where he was for an instant almost airborne; that little interlude of the ball’s flight, beguiling but deceptive; then, at last, the springing of the trap, the baffling break, the bewildered response, the flying bails. Warne actually bowled only sixteen per cent of his victims. But disintegrating stumps, the bowler’s vindication and the batter’s abjection, are an entire story, accessible to everyone.

These reels hardly did his career justice. Warne bowled 51,347 balls in international cricket, which means that 98 per cent of them did not take wickets. What really counted was the anticipation you experienced in watching him. You wouldn’t be anywhere else. You daren’t look away. He stretched our imaginations, and our credulity, even telling us so: ‘Part of the art of bowling spin is to make the batsman think something special is happening when it isn’t.’ We were in the presence, then, of a master illusionist. To vary Arthur C. Clarke’s line about technology, any sufficiently advanced leg-spin is indistinguishable from magic.

To reinforce this illusion, to practice what in magic is called ‘misdirection’, Warne brought a deliciously expressive repertoire of gestures: gasps, grins, moues, imprecations, scowls and stares. He could not even stand at first slip inconspicuously, given his unmistakable crossing of the legs between deliveries and his custom of favouring a broad-brimmed sun hat lightly disturbing the baggy green consensus. But it was when he ceremoniously surrendered this hat to the umpire that you took your seat to enjoy the show, starting with the trademark rub of the disturbed dirt in the crease and the casual saunter back.

The tennis writer Richard Evans once described the contrast between John McEnroe in repose and in action, how the spindly, puffy-haired, flat-footed figure at the baseline suddenly electrified when the ball was in flight. Warne accentuated this by first simply walking - walking! - to the crease. He might have been approaching the umpire to ask the time. Then, to borrow a recent movie title, everything everywhere all at once, the seamless delivery stride and follow through - the bowling action kept in trim by Jenner, altered over the journey really by age and attrition but then but slightly.

Contrast, too, what was commonly believed about Warne’s skill before 3 June 1993, and how he compelled us to adjust our understandings. For the decades before Warne, only Bhagwat Chandrasekhar, sui generis, and Abdul Qadir, rara avis, had nourished belief in leg-spin’s match-winning properties. Leg-spin, we were advised, was an unpredictable faculty, an expensive luxury. It involved a great variety of deliveries. It lured batters to destruction by indiscretion. It needed congenial conditions, including dry, dusty or disintegrating pitches. It needed constant innovations to stay ahead of batters working one out which precluded attention to the game’s other departments. Captains might deploy leg-spin to afford their fast bowlers some respite. Otherwise it bordered on anachronism.

Apart from a fond regard he expressed for Qadir, Warne shows no signs of having watched any leg-spinner before him, or partaken of any of the skill’s associated folk wisdom. By his own profession, his boyhood backyard heroes were Aussie pacemen, macho and theatrical, and batters, tough and leathery. That is completely understandable. When Warne came to England that first time, it was fully thirty years since Australia had tackled an Ashes with a world-class purveyor of wrist-spin - it was a coincidence that that cricketer, Richie Benaud, was calling the Manchester Test when Warne came on to bowl to Gatting that first time and was there to pronounce, now and ever more: ‘He’s done him.’

By the time Warne had departed the Test stage, he had repudiated all those prior beliefs. Warne’s cardinal virtue as a bowler was as much his accuracy as his degree of spin. He bowled with prodigious precision and relatively few variations; he hemmed batters in from all angles including round the wicket, and succeeded in all climes and countries. The discrepancy between his home and away bowling averages was less than two runs; his record was poorest, ironically, in India, previously held to be spin’s great citadel. Nor did Warne revert to the mean: in the fourteen years after the Ball of the Century, his bowling average fluctuated by no more than 5 runs, while his most successful twelve-month periods were separated by twelve years (72 wickets at 23 in 1993, and 96 wickets at 22 in 2005).

Above all, Warne was never other than a frontline weapon. He saw bowling defensively as a contradiction in terms. He never sought protection or reinforcement. On the contrary, he rejoiced in being the sole spinner in the Australian line-ups of his era, and was notably less effective in partnership with another gifted leg-break bowler in Stuart MacGill. When MacGill supplanted him for a Test in Antigua in 1999, he never forgave his captain Steve Waugh.

His great confrere was instead Glenn McGrath, a pace bowler with similarly robust core skills, and a similar mix of patience and aggression. Warne enjoyed batting, was handy enough at number eight to allow Australia to do without a bona fide all-rounder, and excelled in the field, taking 205 international catches. No wonder Jenner was amusedly frustrated with Warne: he was leaving accumulated knowledge and established ideas in the dust.

Warne was also busily transcending our conception of a cricketer in the culture. It need hardly be said that he rewrote the book on fame. In Australian before him, Bradman had set the standard for deportment in greatness - a monument as much as a man, a faintly austere figure rather sealed off by his renown. Warne ascended no pedestal. By his colourful lifestyle he made privacy elusive, but by his personality he made public dealings easy. In the aftermath of his death, it seemed that almost everyone had their own Warnie story: he had a capacity for seeing others, for recognising them, for making them feel a little special. There had been glamorous cricketers before Warne: Miller and Compton, Lillee and Imran. But nobody tackled fame so willingly, so hungrily, with an enthusiasm almost ingenuous.

Especially once introduced to social media, which allowed him to monitor and regulate his interaction with the outside world, he provided cheery relief from seriousness, and in a way that seemed breezily natural. ‘If you’re happy all the time,’ he would say, ‘good things will happen to you.’ Notwithstanding that the latter also helps the former, he matured into a splendid advertisement for being famous, seeming to enjoy every minute of it.

But the celebrity perishes with him; it’s as a cricketer Warne will endure. Warne unveiled his own statue at the MCG; now half the ground is named for him. When the Melbourne Cricket Club foreshadowed the Great Southern Stand in 1991 by explaining that the structure was ‘too significant in every sense to be named after any one individual cricketer, footballer, administrator or public figure’, and expressed the conviction that ‘posterity will support the decision’. When the Victorian government decided within hours of Warne’s death that the structure would be rebaptised the Shane Warne Stand, it seemed like the most natural thing in the world.

It’s arguable that Warne has, quite inadvertently, proven a mixed blessing for those striving to following his example. It was expected he would inspire a generation to take up slow bowling, and perhaps he did, but he also set a standard that made it difficult for them to persist. Australia’s mens team restlessly turned over a dozen spinners in the five years after his retirement before settling for the phlegmatic finger spin of Nathan Lyon. Warne’s most successful imitators, unexpectedly, have been female: Australia’s Alana King, Georgia Wareham and Amanda-Jane Wellington.

The only bowler Warne did not overawe, perhaps, was himself. After the day’s play in that Old Trafford Test thirty years ago, Warne recalled in his autobiography, he and his colleagues sat around the dressing room watching a BBC wrap of the day, and replay upon replay of the delivery in question. ‘Mate,’ averred his keeper Ian Healy, ‘that is as good a ball as you will ever bowl.’ A daunting idea, one might think, at twenty-four. What to aim for now? What to do next? So it was that he started on the path to becoming as good a slow bowler as there will ever be.

Warnie, eh? Age shall not weary him, nor the years condemn. But don’t let On The Ashes stop you from buying my other book, thereby easing the burden on my kitchen, or booking for our live podcast, for which tickets are selling fast. I, meanwhile, have already bought six of these….

No matter how good McGrath, Gillespie, McDermott, Fleming et al were the arrival of Warnie at the crease was worth all the waiting time.

Masterful purity, thank you.