SIX EDUCATION

GH on sixes, Alletson’s Innings and Jessopianism

The Hundred starts tonight (23 July) and its perceived success, as last year, will be largely measured out in sixes: the six has become, as I put it a few years ago, ‘the currency of cricket’s economy.’ In Brave New World, it was ‘the more stitches, the less riches’; in the IPL is the more sixes, the more riches. The seventeenth IPL was the rapidest and richest.

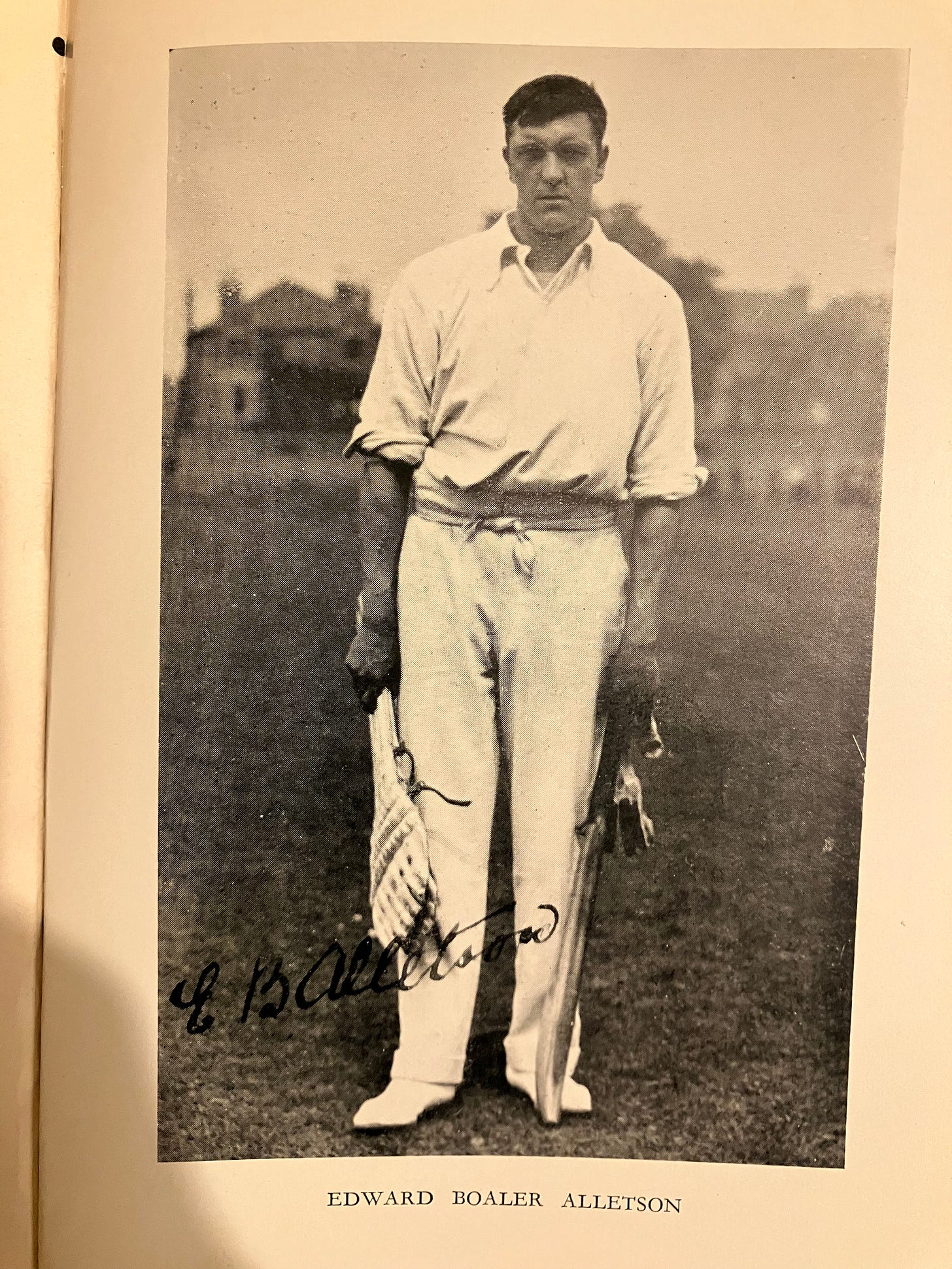

Withal, periodically we are reminded that fast scoring has an antiquity. Recently I re-read John Arlott’s delightful cameo, concerning Ted Alletson’s one crowded hour of glory. Alletson was not a distinguished cricketer; he was not even a consistently successful hitter, and passed fifty in only fourteen of 179 first-class innings. But one day for Nottinghamshire against Sussex at Hove in 1911, he hit 189 in an hour and a half, which enchanted Arlott to such a degree that he began to correspond with the cricketer for the sake of Alletson’s Innings (1958), an account of ‘the most remarkable sustained hitting innings in first-class cricket.’

Cricket Country has a blow-by-blow recapitulation and the indefatigable Old Ebor has the drum on Alletson’s unhappy life, over which Arlott drew a discreet veil. But the specificity of the author’s purpose, I think, dramatises the historic difference between batting and hitting. To Arlott, Alletson embodied hitting as surely as Jack Hobbs embodied batting, the subject of his other exquisite short book. ‘No man,’ he said, ‘has ever won a place among the historic figures of cricket on briefer evidence than Ted Alletson.’

In Alletson’s time, the benchmark for hitting was Gilbert Jessop, the low-stooping, long-handled smiter best known for his epic hundred at the Oval in 1902, and a decided rarity in cricket history for having his name pressed into adjectival service - for a generation and more, to hit spectacularly was to be ‘Jessopian’. Hitting, of course, speaks all languages. The word was as popular in Australia as in England, where exponents included Norman Ebsworth, Jack Ryder, Tibby Cotter, Stan McCabe, Bob Christofani and Sam Loxton.

One interesting feature I noted in looking at the word’s usage hereabouts was its widespread application at lower levels of the game: ‘Jessopian’ hitting in local cricket was reported at Hay in 1902, Wollongong in 1903, Kogarah in 1907, Maryborough in 1908, Orange in 1910, Perth in 1916, Goodna in 1918, Nimbin in 1924 and Lismore in 1925.

I dare say that few very of the antipodean eyewitnesses to the Jessopian had seen the actual Jessop, who because of his sea-sickness only came once to Australia, with little success - this, then, was a word cricket needed, for a phenomenon by definition exceptional.

Nobody did Jessopian more authentically, of course, than the man himself, although even my biographical subject ‘Barlow’ Carkeek could indulge - another reason that I suspect his adhesive nickname was ironic. Women could be ‘Jessopian’, so could Canadians, South Africans and Indians. The word appeared in the context of hockey and of billiards. There was even a Pennsylvanian baseball team called the Jessopians. Are they by any chance related? I think we should be told….

Periodically post-Jessop the cry went up for a return to Jessopianism. In 1929, for example, the likes of Arthur Mailey and Percy Fender thought it was what cricket needed - Fender could say that he led by example. Then, I dare say, came Bradman, who combined fast scoring with vast scoring in a way that boggled all batting minds. The Don rather disapproved of big hitting: ‘It is unwise for a batsman specifically to make up his mind before the ball is bowled where he will hit it. The really fast scorer over a period is not the wild slogger.’ And so, perhaps, Jessopianism fell into decline.

Now, of course, Jessopianism is back with a vengeance, and an index of success. But the word has gone, and no equivalent has emerged. Is it because batting and hitting now overlap so thoroughly, and six extravaganzas are everyday and routine? It used to be mind boggling that Chris Gayle hit more or less every tenth delivery he faced in the IPL for six; but now so does Sunil Narine. I was looking at the stats for the GT20 the other day, and all that’s on offer is a digest: 25 matches, 434 fours, 173 sixes. Under the heading ‘Cricheroes’, covering individual performances, one reads: ‘Heroes of the tournament(player of the tournament, best batter and best bowler) will be published by organiser after the final match. If you don't see them even after final match, contact the organiser.’ A year on, nobody seems bothered enough to have asked. The T20 machine - you put in money, it spits out sixes, and in turn begets more money…..

When the daily pace of cricket is headlong, too, we fall in step with it. One of the delightful features of Alletson’s Innings is that it defied quantification. Even Cricinfo’s statistical review is vague on the boundary count, while Arlott toiled hard over the order of events. It all happened, as he said, too quickly:

It seems that there only a single reporter on the ground; at any rate only one series of figures and times was given, and they are so manifestly inaccurate as to argue single rather than general error….Harry Coxon, the Notts scorer, was well into his sixties, and his fugues were not well made; in any case, few men could have maintained a cold, statistical objectivity as the most spectacular hitting ever seen went on before their eyes.

Maybe that’s what Jessopianism was - not big hitting merely but scoring that defied the average onlooker to follow. In which case, it’s probably only right that the adjective dwindled away. Scoring rates are faster than ever, but so is record keeping and quantification. At any rate, the six counter starts at zero tonight, and the cash register too.

Don't forget that for the first ten years or so of Jessop's career over the fence was five, and you lost the strike. You had to hit the ball out of the ground to get six. These days to get six you only have to hit a rope that is placed metres inside the fence or (better) persuade the fielder who has just caught you to step on that rope, so it's not surprising that so many more are hit. It's a good thing Jessop was an amateur -- he would have been ashamed to take the money.

Correction to what I posted yesterday. Over the fence for 5 (and go to the other end) was an Australian thing. 22 fives let Trumper keep the strike during his legendary 335 for Paddington at Redfern Oval in 1903 -- he would plonk one over the fence at the end of an over, and save the window smashers for earlier on. Australia increased the reward for over the fence to six in 1905, but England kept to four until 1910, by which time Jessop was nearly done. They allowed six for out of the ground. (My source is the ultimate desert island cricket book, Gerald Brodribb's Next Man In, pp 121-22).