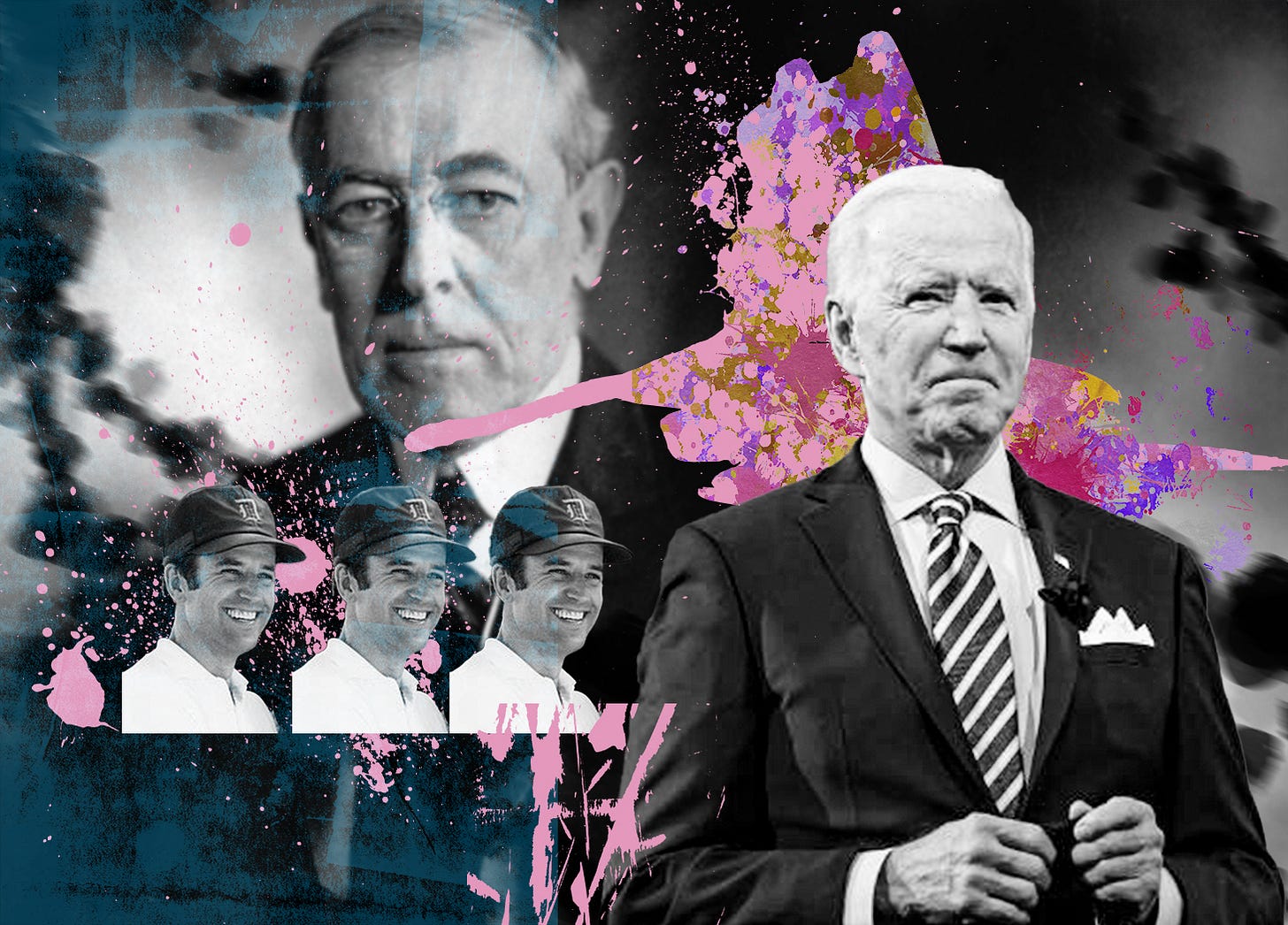

THE CAPTIVE KING

GH on the parallel lives of Joe Biden and Woodrow Wilson

A Democrat president lost in a mental fog. An inner circle led by the First Lady sustaining the illusion of his continued powers. An incurious press accepting their bromides. A Republican rival emerging to street the subsequent election only to plunge the presidency into moral squalor. It could be the fall of the house of Biden, yes? But if you enjoy your White House history, you’ll recognise the scenario of a century ago, when Edith filled the power vacuum left by her bed-ridden husband Woodrow.

It is, at any rate, an old, old story. In 1792, sixty-year-old George Washington worried aloud in a letter to Thomas Jefferson that his memory was deteriorating and his mind decaying; he sought re-election anyway. During the subsequent political crisis with France, Jefferson commented that Washington’s decline in acuity caused the president to let ‘others act and even think for him.’ Said the third American president of the first’s second term: ‘His memory was already sensibly impaired by age, the firm tone of mind for which he had been remarkable was beginning to relax.’

In theory, democratic checks and balances should militate against the gerontocracy characteristic of authoritarian regimes: think Lenin and Stalin, Mao and Deng. In practice, the presidency’s many protective layers can delay a reckoning. Many occupants of the Oval Office have been unwell men, even the youngest, John F. Kennedy, afflicted by Addison's Disease, prostatis, colitis, and chronic backpain, not to mention indiscriminate priapism.

None have suffered more, or been protected more vigilantly, than Wilson, the arrangements for whose last two years as president, says his biographer A. Scott Berg, constitute ’the greatest conspiracy that had ever engulfed the White House’. In the process, his famous Fourteen Points for postwar stability went by the board, replaced by what Keynes called the ‘Carthaginian peace’ of the Treaty of Versailles.

The extent of the deception has been argued ever since, at first in the competing narratives of Woodrow Wilson as I Knew Him (1921) by presidential secretary Joseph Tumulty and Forty-Two Years at the White House (1934) by its chief usher Ike Hoover. I am also indebted here to Lee Levin’s Edith and Woodrow (2002), a fascinating dual biography, and When Illness Strikes the Leader (1993) by Jerrold Post and Robert Robins, their classic analysis of ‘the Captive King dilemma’ from Mad King Ludwig to Marcos and Idi Amin.

The most imposing figure, of course, as is Jill Biden today, was Wilson’s wife Edith. It was second time round for both. Edith’s first husband Norman Galt had died in 1908, Wilson’s first wife Ellen had died in 1914; introduced by Wilson’s personal surgeon Carl Grayson, they married a week before Christmas 1915. The new First Lady was, as Levin calls her ‘a woman of narrow views and formidable determination’, dedicated to the president’s health, which was never robust: he suffered chronic hypertension and progressive cerebral vascular diseases resulting in a series of small strokes before his health began collapsing under the strain of the Paris Peace Conference, which kept him abroad for more than six months. Whether Biden is genuinely suffering dementia is still up for debate; in Wilson (2013), Berg conjectures that the condition was the backdrop to his subject’s subsequent physical maladies.

Early signs of the condition inside apathy towards former enthusiasms, increased impatience, self-absorption to the point of insensitivity towards others and a creeping sense of compulsive as well as suspicious behaviour. Most of the symptoms were, in fact, chronic attributes of Woodrow Wilson, and the rest could be credited to a man with little leisure time, a president anxious to return to the Oval Office, from which he had been absent for close to half a year. But Wilson’s current and future symptoms justify its consideration.

At a crucial moment in the negotiation in Paris in April 1919, Wilson was suddenly overwhelmed by high fever, severe coughing, headache and back pain - apparently a virus. But he also exhibited mental maladies to go with it, from the idea that the staff at his hotel were spies for the French to the fear that items of furniture were being stolen from his quarters. On one occasion, he started railing about the decor in his bedroom. ‘I don’t like the way the colours of this furniture fight each other,’ he exclaimed. ‘The greens and reds are all mixed up here and there is no harmony.’ He demanded a complete rearrangement to calm his febrile mind. But a degeneration was obvious when he returned to the US, and his first speech to a joint session of Congress was what Berg calls ‘a dull address full of run-on sentences about the high cost of living.’

Wilson needed approval of the Senate for the Treaty of Versailles and the putative League of Nations, but isolation had returned with a vengeance to American political life. Before Henry Cabot Lodge’s powerful and hostile Foreign Relations Committee of seventeen senators, Wilson cut a figure almost as diminished as Biden at the first debate. ‘To those of us who just looked on and listened, the president was not at his best,’ Tumulty grudgingly conceded. ‘In fact, all through this period he manifested an over-anxiety towards his guests.’

In desperation, Wilson tried to make his peace a popular cause by to taking the issue to the people on a national tour. ‘I know that I am at the end of my tether,’ he told Tumulty. ‘But my friends on the Hill say that the trip is necessary to save the Treaty, and I am willing to make whatever personal sacrifice is necessary to save the Treaty.’ Recalled Tumulty: ‘I took leave to say to the president that, in his condition, disastrous consequences might result if he should continue the trip. But he dismissed my solicitude.’ George Clooney probably now knows how he felt.....

In Pueblo, on 25 September 1919, Wilson suffered a transient ischemic attack, a common prelude to a stroke, drooling, slurring his words and losing his concentration. Within days he had lost control of his facial muscles, and suffered paralysis down his left side side, the likely cause a thrombosis of the right internal carotid artery. Even then, he was reluctant to give up. ‘Don’t you see that if you cancel this trip, Senator Lodge and his friends will say I am a quitter,’ he complained. In fact, he had made his last public appearances. On his way back to Washington by train, he waved to empty vistas as though to massive crowds, then retreated to a state of seclusion that grew permanent, with Edith Wilson standing ‘like a stone wall between the sickroom and the officials’.

In this, Edith had the collusion of the medical establishment, notably Grayson, and Francis Dercum, professor of nervous and mental diseases at Jefferson Medical College. It was on their counsel Edith relied in enforcing her cordon sanitaire, although their advice was subtly contradictory: the president would be fine if spared any of the requirements of being president. Grayson affirmed publicly that Wilson’s ‘intellect was unimpaired and his lion spirit untamed’ while privately despairing; Dercum told Edith that Wilson could ‘still do more with even a maimed body than any one else’, but also that ‘every time you take him a new anxiety or problem to excite him, you are turning the knife in an open wound’. So the myth of personal indispensability was further perverted by the assumption of medical omniscience.

Edith Wilson’s account of the service she rendered her husband was likewise contradictory. She claimed that she ‘never ‘made a single decision regarding the disposition of public affairs’, while also admitting: ‘I studied every paper, sent from the different Secretaries or Senators, and tried to digest and present in tabloid form the things that, despite my vigilance, had to go to the President’. In other words, tantamount to the same thing. The clockwork duly adjusted to the absence of its mainspring. Tumulty cut and pasted a State of the Union address. Twenty-eight acts became law without Wilson’s signature - even the Volstead Act, enforcing prohibition.

Wilson was eventually able to conduct some business from bed, albeit in pathetic circumstances well-described by Berg: ‘At one point a delegation of congressmen came to visit president Wilson. He was propped up, with his useless left arm hidden. The name of each congressman was whispered to him so that he could offer the appropriate greeting.’ But those propping Wilson up could not tolerate dissenters. Vice-president Thomas Marshall remained in place by being weak and acquiescent; stronger-willed old friends like Colonel Edward House and secretary of state Robert Lansing were frozen out. At last, in April 1920, Grayson encouraged Wilson to hold a cabinet meeting. It became a grisly ordeal for all concerned. ‘The president looked old, worn and haggard,’ wrote Treasury secretary David Houston. ‘One of his arms was useless. In repose, his face looked very much as usual, but, when he tried to speak, there were marked evidences of his trouble. His jaw tended to drop on one side, or seemed to do so. His voice was very weak and strained.’

One other attribute that Wilson and Biden seem to share is a messianic belief in their destiny. Just as the Bidens remain convinced he is ‘the only man for the job’, so Wilson went on believing that only he could ‘bring this country to a sense of its great opportunity and greater responsibility’. Support for the treaty petered out in the US; the country stayed out of the League of Nations. Yet Wilson continued nursing the delusion that his party might call on him to run for a third term up to the Democrat National Conference, where he blocked the nomination of his son-in-law William McAdoo in order to improve his chances. Berg posits Wilson being a case of anosognosia - a patient’s unawareness of their incapacity. Who knows whether the same may apply to Biden?

In the event, the nomination went to the genial Ohio governor James Cox, and Wilson withdrew into further isolation. His return to the law was foreshadowed then quietly fizzled out; he died in January 1924. Ten years later, Hoover effectively acknowledged what had previously been rumoured about Wilson’s post-stroke presidency: ‘There was never a moment during all that time when he was more than a shadow of his former self. He had changed from a giant to a pygmy in every wise.’ There has been a wide divergence of opinion ever since, with the extremes represented by Edith Wilson’s self-justifying My Memoir (1939) and William Bullitt’s fanatical Thomas Woodrow Wilson: A Psychological Study (1967).

Bullitt, a protege of Colonel House’s who had served on the American mission at Versailles, had been bitten by the Bolshevik bug then antagonised by the president’s reluctance to recognise Soviet Russia. After his own nervous breakdown in the mid-1920s, Bullitt underwent an analysis by Sigmund Freud that turned into a friendship then an extraordinary collaboration: a psychobiography of the twenty-eighth president. This bizarre mixture of psychoanalytic jargon and beltway gossip argued that Wilson, a passive homosexual in the grip of his Oedipus complex, was effectively killed by his stroke - afterwards he was merely ‘a pathetic invalid, a querulous old man full of rage and tears, hatred and self-pity.’ But when Bullitt found himself in the running for the role of US ambassador to the USSR, he decided not to publish, and the book did not appear until both co-authors were dead. They were spared its widespread ridicule, by reviewers such as Robert Cole in New Republic: ‘The book can either be considered a mischievous and preposterous joke, a sort of caricature of the worst that has come from psychoanalytic dialogues, or else an awful and unrelenting slander upon a remarkably gifted American president.’ Wonder what Michael Wolff’s up to right now…..

Whatever the case, it is hard to dissent the view expressed by Post and Robins in their groundbreaking study thirty years ago: what gets you is not the failure of the leader so much as the attempt to cover for them. ‘Leaders are flesh and blood, subject to the vicissitudes of the life cycle, prone to illness and aging will continue to have tremendous consequences for society,’ they said. ‘Should the leader and his inner circle conceal the illness, profound distortions in leadership dynamics and decision-making can occur as the captive king and his captive court become locked in a destructive and often fatal embrace.’ In Wilson’s case, profound distortions ensued: the advance of a manifestly incapable successor. Republican Warren Harding vanquished Cox at the polls and proved one of the worst presidents in history, corrupt and incompetent. History couldn't repeat, could it?

And then there was Ronald Reagan whose dementia diagnosis was announced five years after his second presidency ended. The trajectory of dementia is such that it is certain he suffered at least its prodrome, Mild Cognitive Impairment, when in office when he was politely described as disinterested (might explain his ignorance about the Iran Contra affair). It doesn't matter whether Biden has dementia or not, the situational complexity of the task at hand is what matters in capacity assessment: he might be able to oversee the Seattle Orcas franchise but US Forces? [cue the Oils].

A welcome check to my own tendencies to regard current circumstances as unparalleled. Harding is always a good reminder of how debased in their venality US presidents can be.