The Girl in Cabin 350

Dossier of a disappearance...

Gideon Haigh

This time last year I was asked to launch a posthumous memoir, Cannon Fire, by the Australian journalist Michael Cannon. In it, he recounted an encounter with a young woman, ‘Gwenda’, whom he attempted unsuccessfully to seduce, then lost touch with - only to be confronted with her photograph on the front page of Melbourne’s Herald, which was reporting her disappearance from the liner Orcades. In-te-res-ting, I thought. A few keystrokes garnered more: nineteen-year-old nurse Gwenda McCallum had been dubbed ‘The Girl in Cabin 350’ as her story swept the world, only to dwindle in memory when no further clues to her fate emerged.

It wasn’t long before I felt a book coming on, as the only means by which I would gratify my curiosity. Why might somebody disappear? What impact might it have? What light could it shed on the time and place, 1949 in Australia? So off I set on another quixotic quest that, like all the best stories, was utterly unlike what I had expected, featuring a handsome actor, a bigamous roue, a bold aviator, a secret fascist and a woman with a wooden hand. The book, nonetheless, is just as I had envisioned : a crisp, compact, well-illustrated hardback fetish object, printed in China on lovely creamy paper, ideal as a gift for the mystery lover in your life and available only from my kitchen table. Just email me at www.gideonhaigh.com for further details. For a taste, here’s the first 1000w, concerning Gwenda's last 24 hours, ending on the morning of 31 August 1949. No spoilers.

*

The day was starting slowly. It had been a long night. Evidences lay strewn along the polished decks, through the great maze of interior corridors. Rose petals here; streamers there; even an empty bottle or two. Nearly 5000 had watched the Orcades depart Sydney the day before. Such was the social whirlpool left by a liner departing Australia in the days before air travel shrank the globe, when four weeks to Tilbury seemed almost inconceivably swift.

In its first year steaming England to Australia, Orcades had been chartered by the Orient Line as an immigrant ship, albeit still carrying its share of glamorous passengers: prime-minister-to-be Robert Menzies and family returning from an northern sojourn; General Sir Dallas Brooks and retinue, on the way to accepting his commission as Victoria’s governor. But the reverse route, bearing pilgrims to the centre of Empire and the starry-eyed to Europe, was the fun one. For a week before its departure, Sydney’s social pages would chronicle farewell soirees. Reporters would then converge on Darling Harbour to capture the gala of embarkation, the shipboard parties, the quayside throngs.

The latest scene at 13 Pyrmont had been specially boisterous. In light of an aviation fuel shortage, Orcades, along with the liners Strathaird and Moreton Bay, had been licensed to carry passengers round the Australian coast before commencing their hauls to Britain, dropping them off in Melbourne, Adelaide and Perth. Fully seven-hundred and fifty of the 1100 on board Orcades were bound for Melbourne, where the Melbourne Cup was to be run on Tuesday. ‘Bookmakers, urgers, gamblers, confidence men, players and socialites’: Truth enumerated them in its racy style. The Orcades’ switchboard (MW110S) rang off the hook. Young people in Tourist Class dashed from gathering to gathering. The crew, a junior assistant purser remembered, did their best.

Moving round inside the ship was difficult [on mornings of departure], and trying to get from the Purser’s office to Captain’s cabin with an arm full of papers to sign was an ordeal. Every few yards a visitor would stop me and ask the way to a particular cabin or suite, or perhaps just to say, ‘Say, skip, this boat a roller?’ or ‘Say, mate, what’s the tucker like on this boat?’ Getting them all ashore was a miracle.

With an hour to go before noon departure, the loudspeakers began issuing the command: ‘All visitors ashore! All visitors ashore!’ Final farewells began. Moves were grudgingly made, last-minute dashes taken. Pressmen captured a few of the more captivating interludes for posterity: a red-haired, sun-bronzed ’French mannequin’ was seen ‘to embrace a dark, handsome Australian friend on the wharf’; after they held hands and ‘exchanged addresses’, she was observed weeping among the hundreds of her fellow passengers lined at the rail. Then, at last, Orcades peeled from the quay, horn booming, funnel exuding a sliver of steam. Confetti rained; multi-coloured streamers unfurled; the ship’s master, Captain Charles Fox, aimed for the Heads, which were cleared at 1.18pm. But the ‘miracle’ of shooing all the guests from the ship had not quite been accomplished.

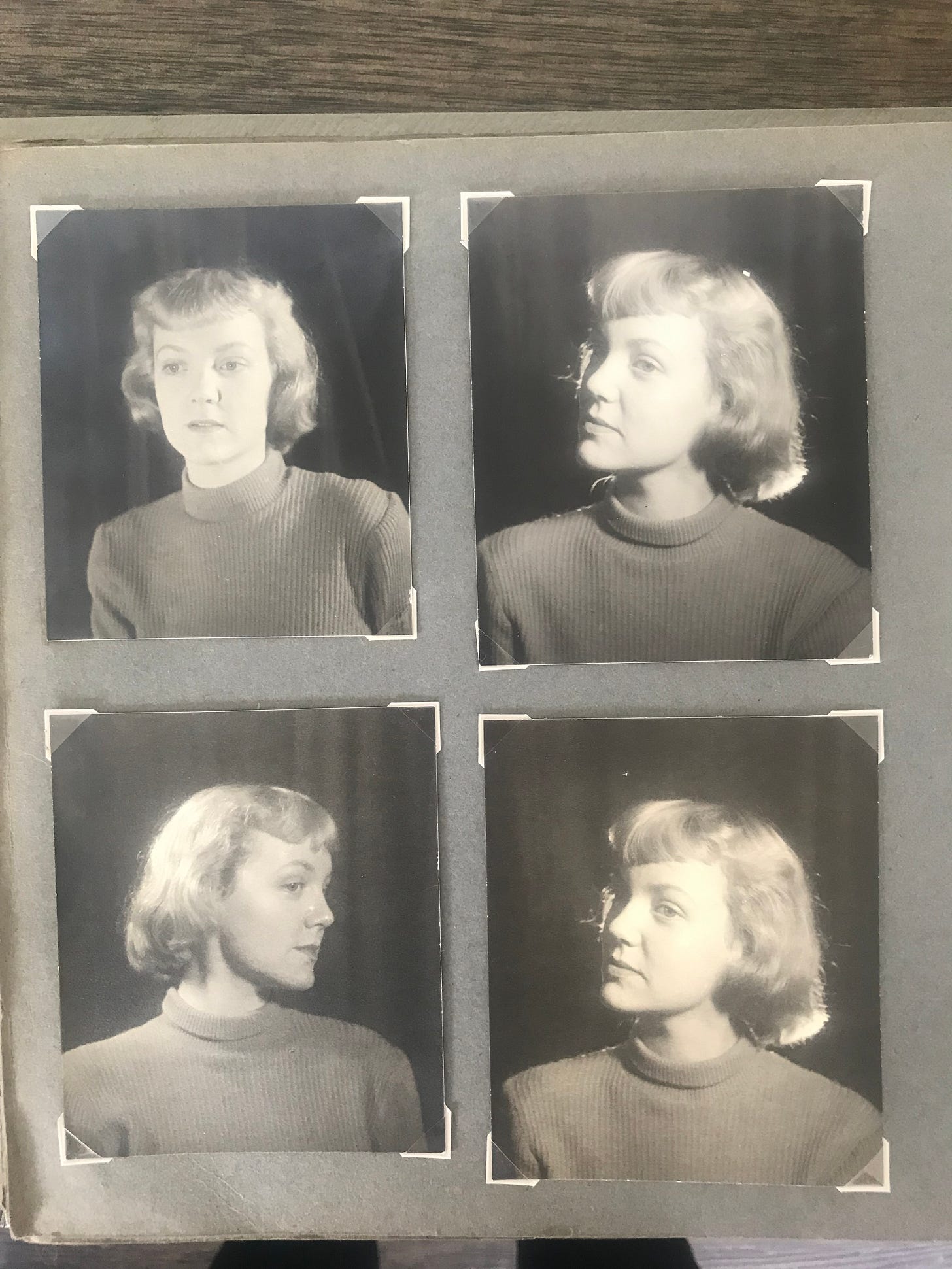

The press would later describe nineteen-year-old Gwenda McCallum from Melbourne, with an exotic flourish, as an ‘attractive blonde stowaway’. This was by effect rather than design. She had been in Sydney for three weeks, falling in with the social circle of a well-heeled couple, Pierre and Margaret Mann. On the Friday night they had gathered at the Australia Hotel in Martin Place, and there made the acquaintance of a 30-year-old Englishman, Alastair Cameron, homeward bound on the Orcades after a stint as a colonial service official in Fiji. The swelling party had carried on to a night club, then to the Glebe home of a young clerk, Ian Ricardo.

Somewhere along the line, the Manns and Ricardo decided to join Cameron on the leg of the journey to Melbourne. Having bought tickets and gone aboard on Saturday morning, they had continued festivities with an impromptu party. There was excitement about Derby Day later in the afternoon. Tips were being exchanged, healths toasted, and at some stage, it seems, Gwen laid her head down, dozed off and slept deeply - so deeply that neither the ship’s loudspeakers nor its lurching roused her.

Not that this would have seemed to matter overmuch midst the general gaiety. No sooner had the Orcades shoved off than bookmakers opened a tote among the panelled walls and tartanned upholstery of the tourist lounge, accepting bets on the day’s races, not only from Flemington but also from Sydney’s Moorefield. Other gamblers opened card schools on the decks outside, and started tearing up housie housie tickets.

As the Orcades turned south, punters gathered round a radio to cheer the favourite, Chicquita, to victory in the Wakeful Stakes. Second favourite Mighty Song then came home in the Maribyrnong Plate, and favourite Comic Court in the L.K. S. McKinnon Stakes. In rough weather, the Orcades was known for a tendency to roll, for which she was nicknamed ‘Rocades’. But on this sunny, windless day, she felt less like an ocean liner than a floating race train, making Spring Carnival waiters of the ship’s 400 crew. There was uproar just before 3.30pm when three fancied horses came down at the mile and a quarter barrier in the Derby, the Sydney-owned and trained Delta proceeding to a runaway victory.

It was around this time that Gwen awoke. She had neither ticket nor penny nor plan. Not to worry, her friends assured her. Overstayers were common: Orient Line pursers had the discretion to allocate them unoccupied cabins, of which on this trip, during the off-season for northern tourism, there were many. So it was that, with the shipboard spirits at their highest, Cameron not only gallantly gave Gwen £20 to cover her fare to Melbourne but offered her a spare pair of white pyjamas. A steward guided her to a twin berth on D deck: Cabin 350. From which, sixteen hours later, she was discovered to be missing.