THE PAINTED WOMAN

GH on an ancient murder and a newly discovered artwork.

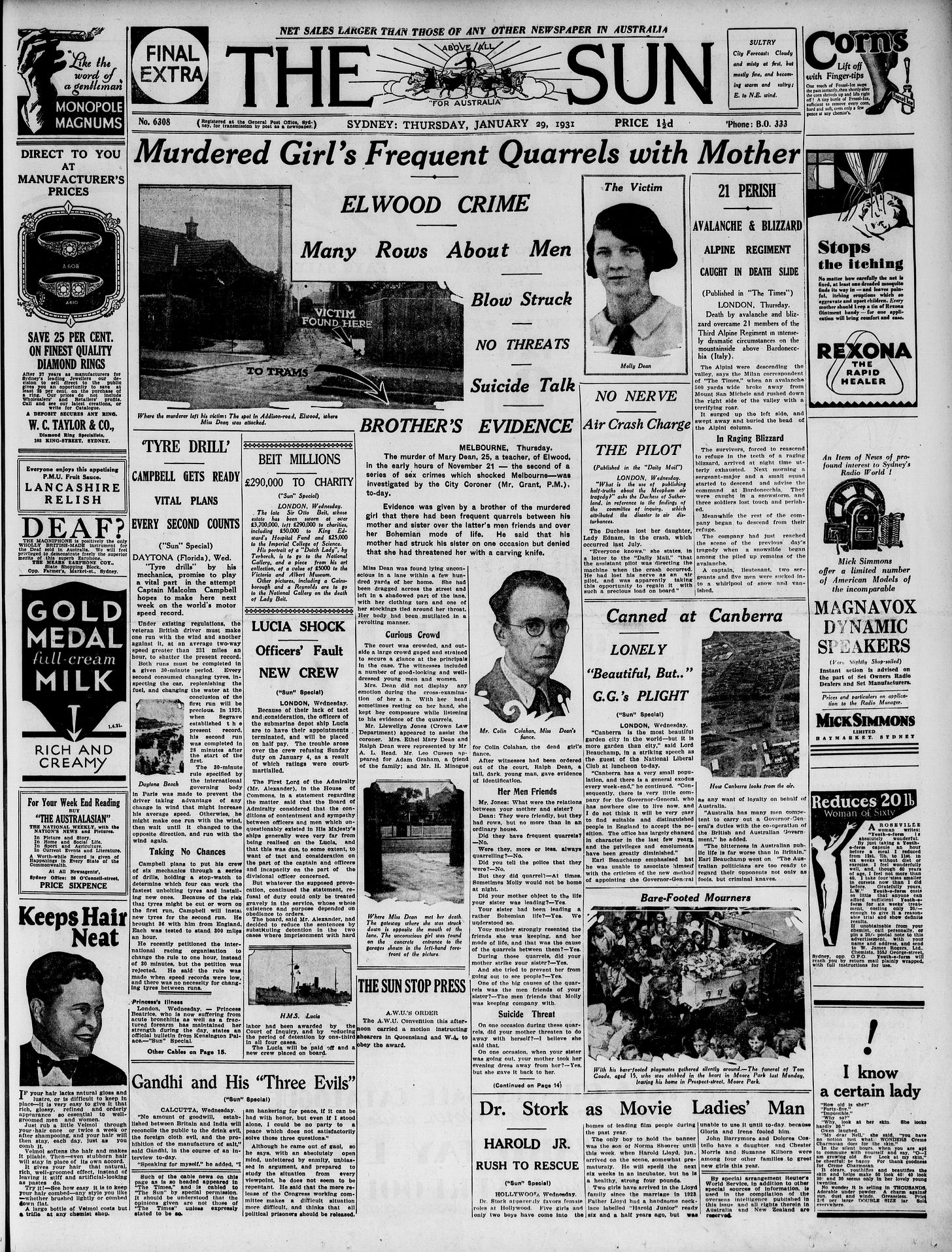

At around 12.40am on 21 November 1930, twenty-five-year-old teacher Mollie Dean was attacked from behind as she passed the gate of 5 Addison Street, Elwood. Her assailant coshed her with what was probably a tyre iron, dragged her disabled figure across the road into a dark bluestone laneway, where he continued to strike her, attempted to tie her hands with a portion of her unskirt and strangle her with one of her stockings. He also violated her with his bludgeon, before perhaps being disturbed, whereupon he slipped away down the diagonal lane that exits at Milton Street into anonymity - for he was never identified. Mollie died at about 4am in the Alfred Hospital, convulsing the city as such murders do, especially as she had formed part of a colourful circle of Melbourne’s artistic, literary and musical bohemia.

In 2018, I published a book about Mollie, and her personal and cultural echoes. At the time of her murder, Mollie, who had published several poems and short stories, was trying to write a novel, of which only the title survives: Monsters Not Men. But she has had a remarkable creative afterlife. At least three of her circle cast her in novels they wrote that remained unpublished in their lifetimes: A Pressman’s Soul (c1940) by the journalist Mervyn Skipper, one of her friends; James Comes Home to Dinner (1942) by the composer Fritz Hart, one of her lovers; The Cruel Man (2002) by Sue Vanderkelen, her rival for the love of the painter Colin Colahan. Most famously, Mollie Dean and Colin Colahan became Jessica Wray and Sam Burlington in George Johnston’s canonical My Brother Jack (1963), twice adapted to the screen, in 1965 by Chairman Clift….

…and John Alsop and Sue Smith in 2001.

Latterly there has been a further uptick of interest: the story of the precociously emancipated woman, an aspiring writer and poet, struggling against the hidebound masculine codes of her time resonates ever better with ours. There has been a play, Solitude in Blue (2002) by Melita Rowston, depicting Mollie as ‘a guffawing, rasp-voiced femme fatale’; there has been a novel, The Portrait of Molly Dean (2018), imagining her as a girl detective; she also pops up in Kristen Thornell’s Night Street (2010), a fictionalised life of Clarice Beckett. In recent times, there have been songs, by the storied duo of Andrew Pendlebury (Sports) and Steve Pinkerton (Dallas Crane), and by Lisa Miller, whose Dusty Millers were kind enough to play at the launch of A Scandal in Bohemia six years ago.

But the artefacts of Mollie Dean that have most captivated me are the paintings. The rediscovery of Beckett has prompted art historians to take a second look at the tonalists - the disciples of Max Meldrum, who also include Colahan, Justus Jorgensen, Percy Leason, Archie Colquhoun, Polly Hurry, Jock Frater and Helen Lempriere, have been lauded as ‘arguably the first important advance in Australian landscape painting since Australian impressionism of the 1880s.’ Mollie was enlisted in their vision for she was Colahan’s model as well as his lover - the roles were not uncommonly blurred at the time, for not every painter could be as sternly objective as George Bell, who exhorted students to think of a nude model as ‘lumps of sausages’. Frater married his model Winnie Dow, Norman Lindsay his model Rose Soady; a later model cum lover of Colahan’s, Patricia Cole, married the poet John Thompson. Mollie was partial to the works of the Irish novelist George Moore, in whose A Modern Lover [1908] shopgirl Gwynnie Lloyd sacrifices herself by posing chastely for her impecunious artist boyfriend, Lewis Seymour: ‘I will sit for you, Lewis, since it is necessary; but I am not a bad girl, nor do I wish to be, but it cannot be right to see you starve or drown yourself, when I can save you.’ Not that Mollie would have seen herself saving Colahan. Rather was she seeking deliverance from the mundanity of her suburban existence.

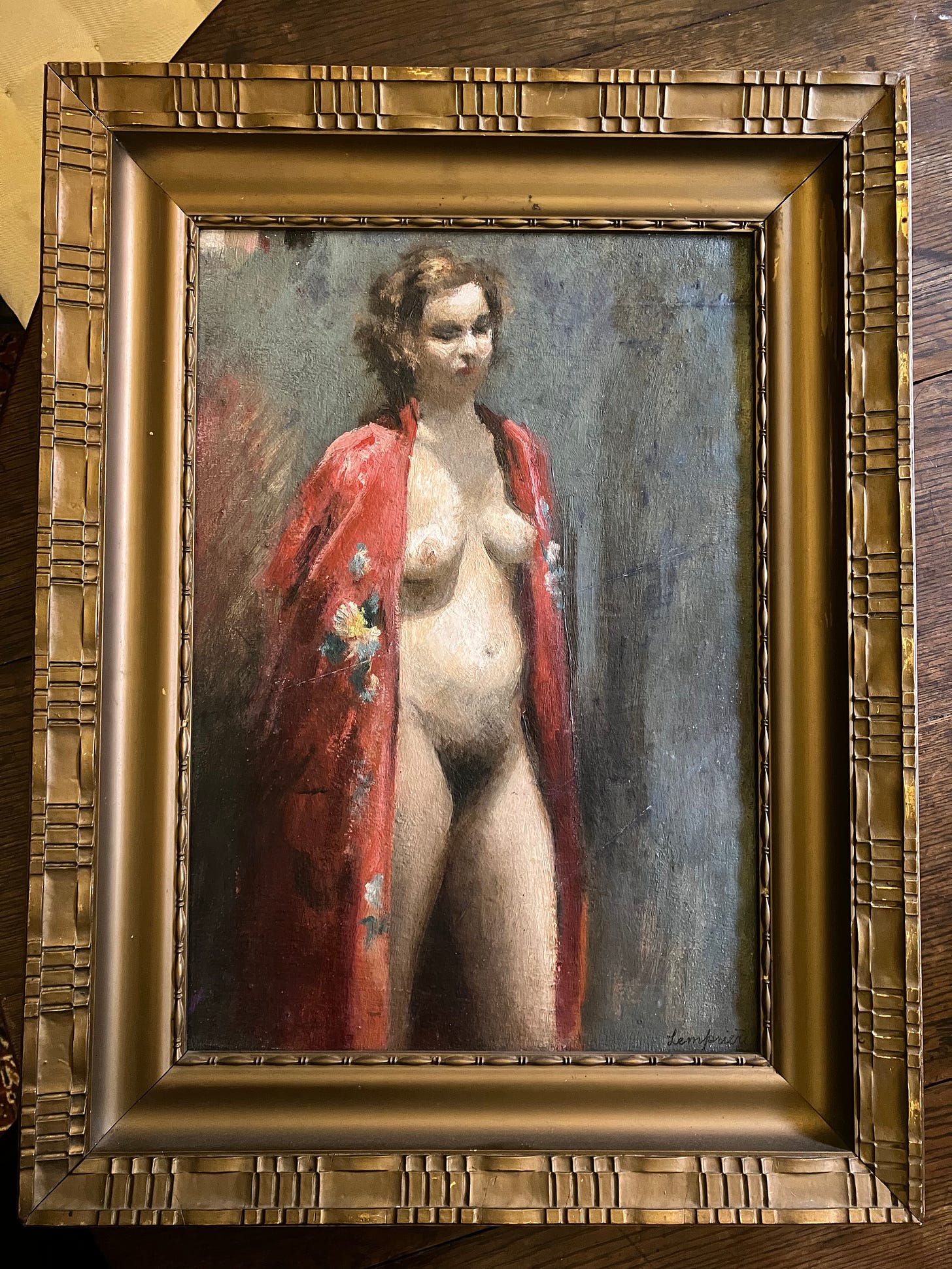

Mollie is probably the slim, small-breasted, contrapposto figure in Colahan’s 1930 ‘Standing Nude’…

…and maybe also this undated ink and watercolour wash sketch.

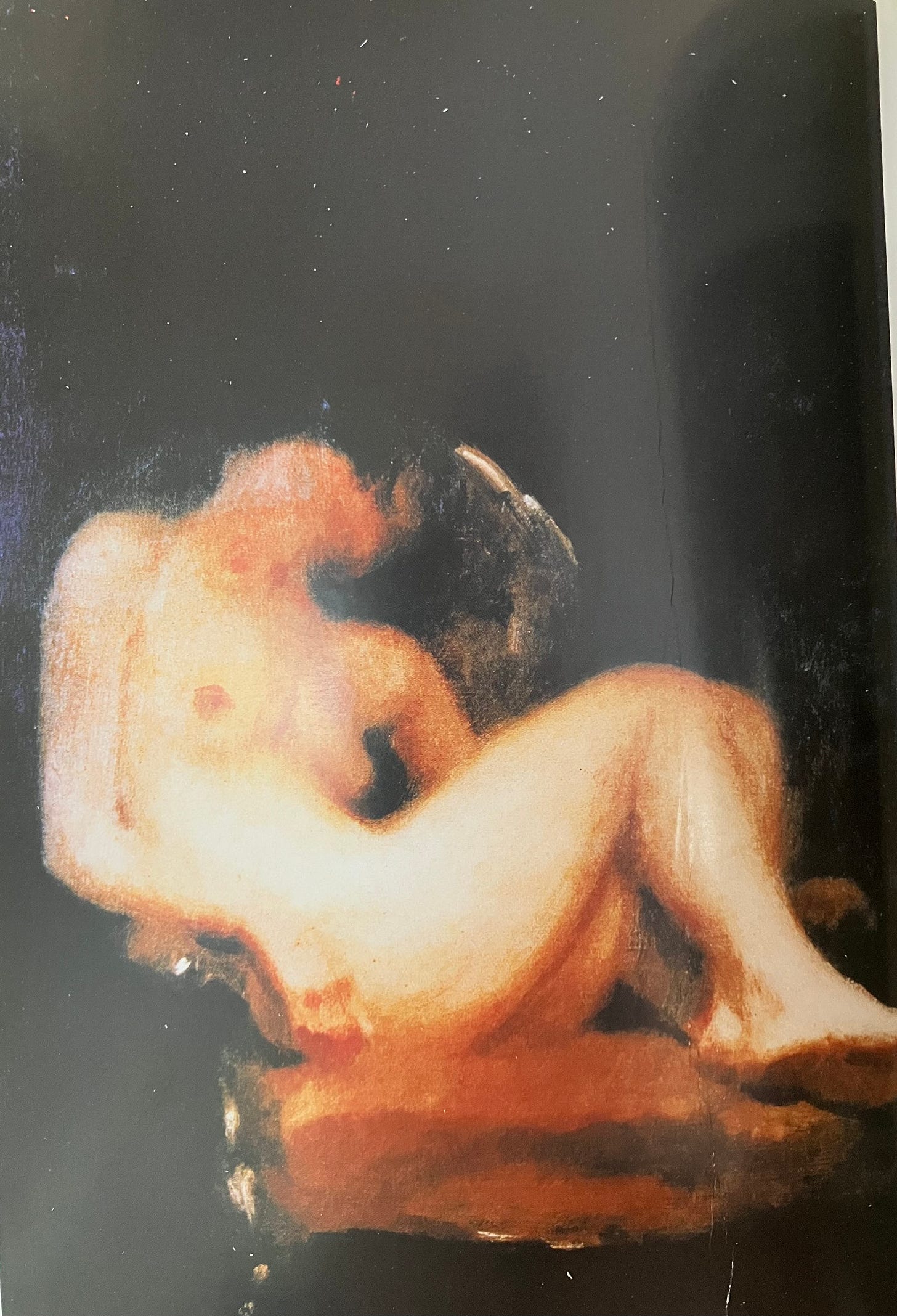

She is assuredly the figure in ‘Sleep’, for it was drying on his easel the night that Mollie was murdered - now in a private collection in Hampton, it would be an astonishing painting even without its provenance, and demanded use on my book’s cover. To quote A Scandal in Bohemia: ‘The skin is as fresh and pink and quiveringly alive as the night the paint was applied to the 71 cm by 50 cm canvas – the night, and there is no escaping it, before Mollie’s death. You are gazing at the painting of a woman doomed to die, of a body a killer was driven to ravage and mutilate little more than twentyfour hours later: one could surely find no tenser overlappings of “the male gaze”, when one man must destroy that which another has sought to celebrate.’

My friend the composer Peter Tregear, meanwhile, suspects that it’s Mollie rocking a pair of red shoes in the undated ‘Interior With Figure’ by Colquhoun in the Castlemaine Art Gallery.

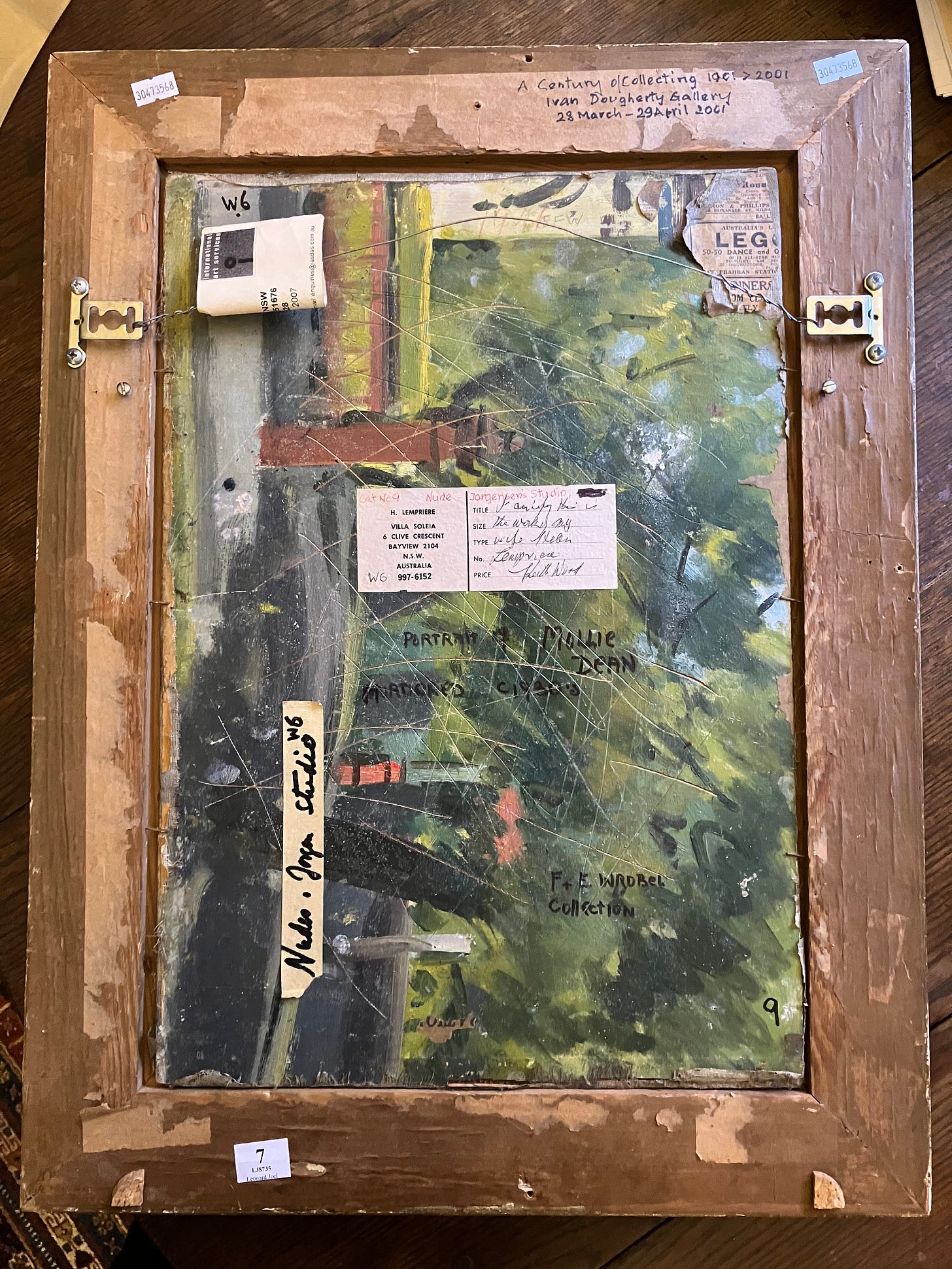

At last comes the amazing find at the top of this column - the undated Lempriere oil auctioned last month at Leonard Joel; the board’s reverse authoritatively identifies the figure in the red kimono as ‘Mollie Dean’ who was ‘murdered 1930s’.

I’m delighted to report it now looks down from the wall of the home of none other than Lisa Miller, whose Mollie Dean obsession is beginning to rival my own, and her partner Ben Lempriere, who also happens to be the painter’s nephew. Helen Lempriere, a niece of Melba’s who studied under first Colquhoun then Jorgensen and was later involved in the building of the tonalists’ great Eltham redoubt at Montsalvat, was two years’ younger than Mollie. I like to imagine them, as Mollie stood for Helen at Jorgensen’s Brighton studio, exchanging acerbic views on the male monomaniacs who dominated their respective worlds.

Meldrum himself believed that there ‘would never be a great woman artist’ for women lacked ‘the capacity to be alone’; he was once heard to praise Hitler for having ‘given women the freedom to be women’. Colahan was barely less dismissive. ‘Colin’s opinion of female intelligence was not, on the whole, very high,’ noted the aforementioned Patricia Cole. Maybe artist and model even discussed Mollie’s Monsters Not Men - unaware, of course, of the monster already lurking. About every story, then, there is always something more to know. Who knows when the past might have more to reveal? You just have to hope to be around when it happens.

Just a fantastic read Gideon - thanks.

Edifying and intriguing…looking forward to reading A Scandal In Bohemia.