The Strange Death of John Bellew

GH finds a missing piece in a historic puzzle

Andrew Gilmour has a story he wants to share. He has thought about it a long time. He knows it sounds a little strange, but life can be.

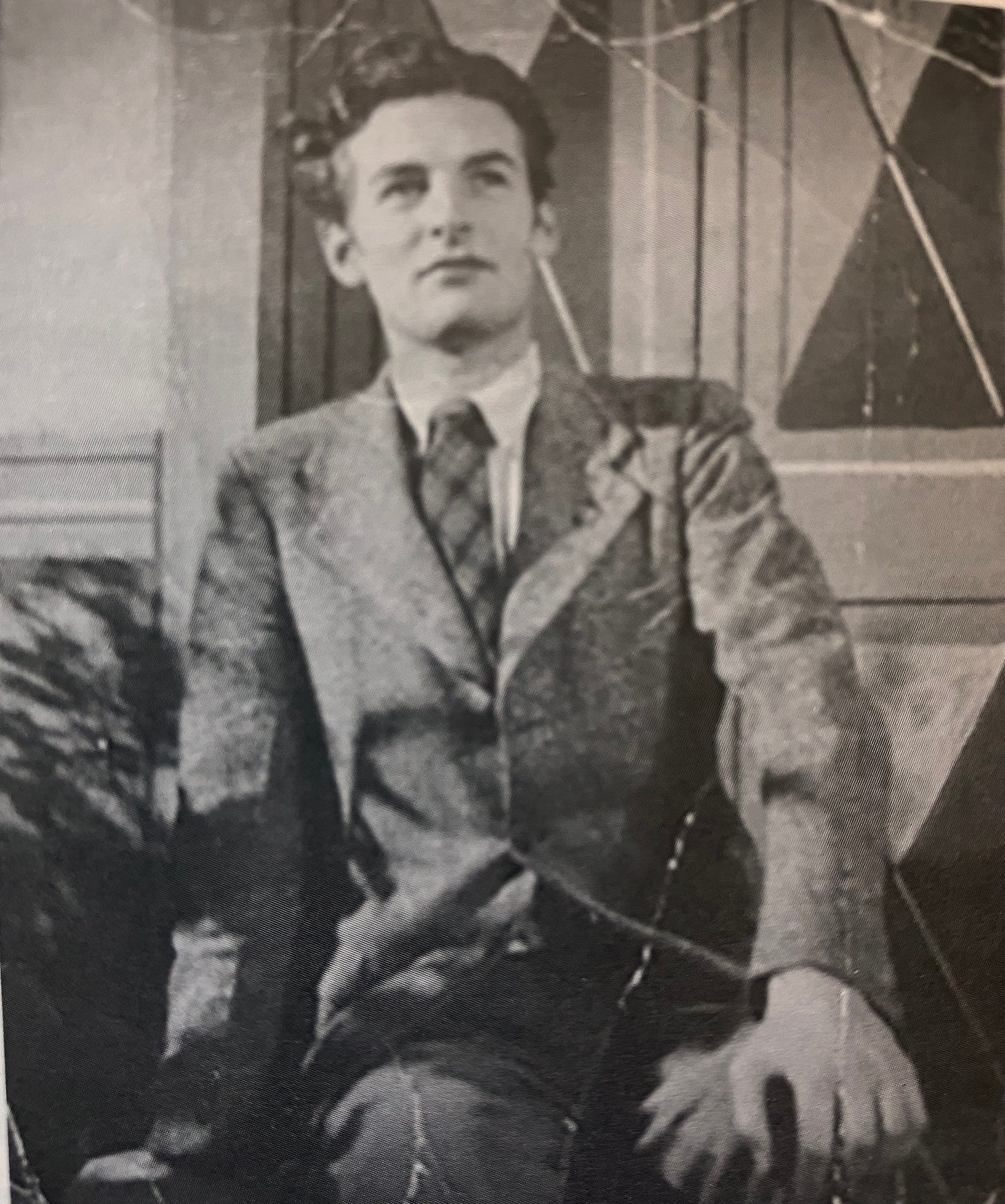

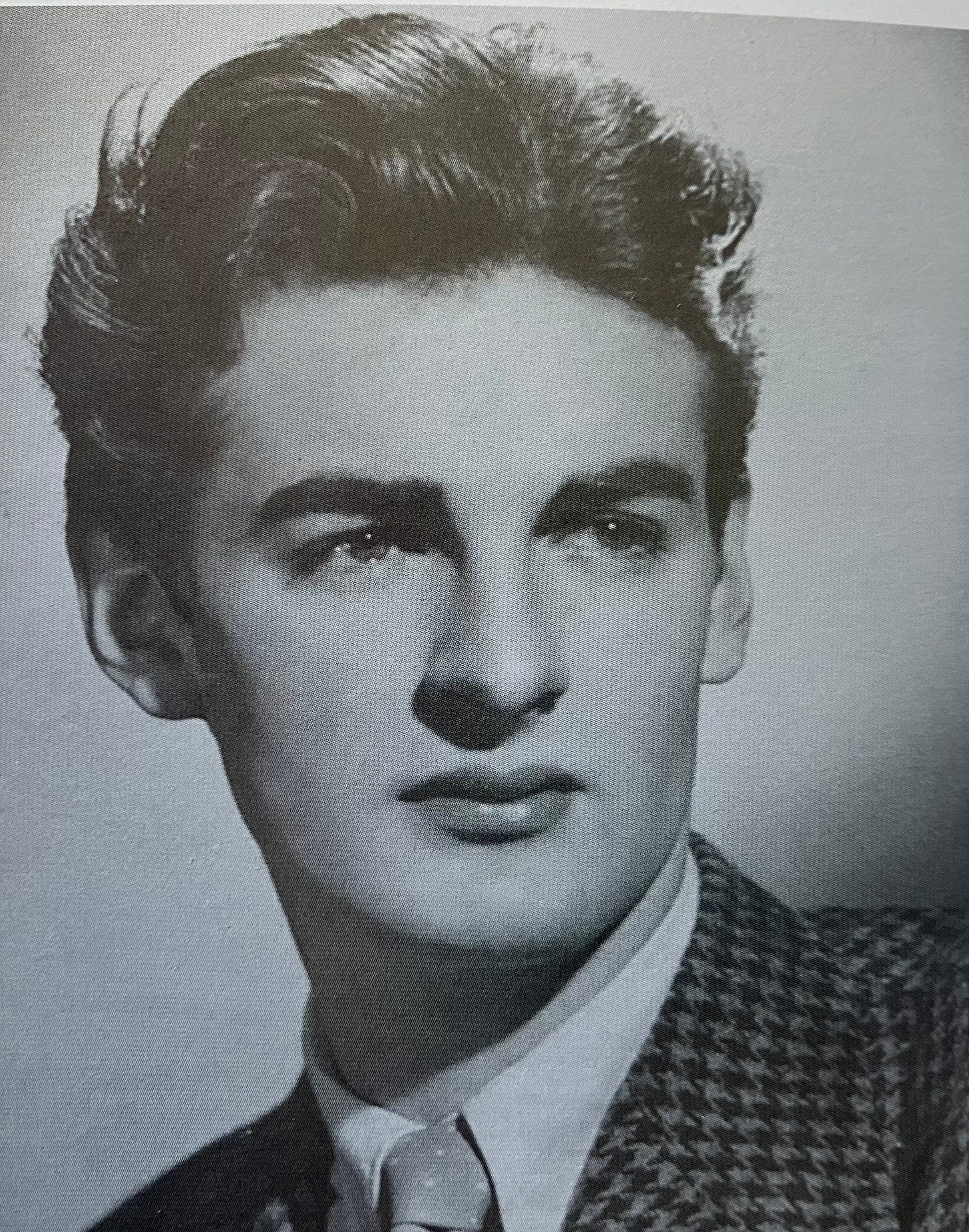

Andrew is now a disarmingly sprightly ninety-seven. He is casting back to events when he was a teenager, as was his schoolfriend John Bellew (above) - the day when they visited a spiritualist in Melbourne’s Block Arcade, who made a business telling fortunes and conducting seances for a clientele skewed to those who had lost sons during the wars.

Andrew and John were not so earnest. In fact, they thought it a bit of a lark to pay their 2/6 for the foretelling of their futures. Andrew was pleased by the spiritualist’s utterances over him. ‘You have a halo of healing,’ she said. ‘You’ll go through life and people will feel better for meeting you.’ After a couple of years in the army, he was set to study medicine.

Over John, however, the spiritualist paused. There was nothing she could tell him. John was mildly annoyed. He was a gifted young actor whose career stretched out before him; he had also paid good money for this. ‘You must understand,’ she said. ‘My powers are quite limited.’ At last she explained reluctantly: ‘I’m afraid I can see nothing after your nineteenth birthday.’

Andrew is a little haunted by that. When John committed suicide on 21 August 1949, he was nineteen; and when Andrew read my book The Girl in Cabin 350, in which the death is described, it was seventy-five years to the day later.

Today is not a grave day. We’re at Abbotsford Convent, where Andrew is holding court. For it was he, rather than his friend John, who ended up having the acting career. Remember Silvertongue, Johnny the Boy’s slick defence attorney in Mad Max? That’s him. Remember Bert Stapler, a foil to Mick Molloy in Crackerjack? That’s him too. He has a wonderful array of theatrical anecdotes, which he relates with flawless timing.

I’m introducing Andrew to John Bellew’s only surviving relative, his ninety-year-old cousin Anne. ‘I’m sorry,’ says Anne by way of introduction. ‘I can’t really see.’ ‘Well, I can’t really hear,’ replies Andrew. ‘So we’ll get on well.’ And they do. They riff delightedly off each other, reliving their youths in the Melbourne of the late 1940s. They speak of the same theatrical productions, and suspect they must have been in the same audiences. They reel off the names of same long-gone, late-night, bohemian haunts. The Raffles? Milady’s? Cinders ? ‘Smoky and dark,’ says Andrew. ‘The coffee was terrible,’ adds Anne.

They both still revere John’s memory. ‘So many people were so fond of John,’ says Andrew. ‘He had so much talent. It just oozed out of him.’ Anne remains besotted. ‘I adored him,’ she says simply. So what happened? I’ve brought them together in the hope of delving a little deeper, for John’s suicide preluded the unsolved disappearance two months later of teenage nurse Gwenda McCallum, subject of The Girl. Hearing from someone who might have a crucial piece of information that might reshape your story is the second worst thing that can happen after you publish a book; the only thing worse is hearing nothing.

If you’ve read The Girl, you already know Anne’s story. Her father, Rex McKell, whom she never knew, was an incurable charmer and chancer, who scattered ex-wives and children left and right. Joan Bellew, the schoolteacher ‘aunt’ who began to visit Anne in the private hospital where she was born in 1934 and lived the first few years of her life, and took responsibility for her convent education, was actually her mother, although many years would pass before this was acknowledged.

Joan’s parents had worked for J. C. Williamson. After her mother’s death, her father had remarried, the union producing two more boys. Thanks to the generosity of a brother-in-law, John and Peter Bellew attended Trinity Grammar, where they met Andrew Gilmour, a boarder, down from Chiltern, a little older, born in 1927. John and Andrew shared a love of theatre, and took their first steps under the tutelage of the eccentric theatrical impresario J. Beresford Fowler. Gassed during World War One, hearing and speech impaired, Fowler drove his Art Theatre Players with antic enthusiasm. As his biographers recount:

Stories of his improvised productions became legendary; most were true. Performers sometimes met for the first time on stage….His manner was Edwardian, courtly, his charm touched with the anxiety of a deaf man trying not to miss out. On stage, he seemed to have everything against him: deafness, a harsh voice which lacked any modulation, a slight speech impediment and a determination to promote plays that commercial managements would not touch. But the Art Theatre Players was an oasis in Melbourne's cultural desert.

For Fowler in 1947, seventeen-year-old John played a host of roles, from Prospero in The Tempest, to Freddy Eynesford Hill in Pygmalion. A reviewer thought John ‘an imposing figure’ at Prince Albert in Lawrence Houseman’s Victoria Regina, even if Anne remembered it for her cousin and his leading lady getting the giggles at his moustache coming away during a kiss. Fowler was also partial to ‘Shakespearian scenes’, in which John joined with a famously flamboyant actress Pat Hoisfield - more of her anon. All these decades later, Anne remembered Hoisfield for a play in which she uttered a single line: ‘Did you receive the melon I sent you?’

The following year, John joined Doris Fitton’s Independent Theatre, and was cast in her touring production of Eugene O’Neill’s epic Mourning Becomes Electra. Australians, in the meantime, were being captivated by the visit of Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh with the Old Vic - to Melbourne theatre as the visit of the Beatles was to music in 1964, and well described in Shiroma Perera-Nathan’s new book God and the Angel. ‘God Save the King’ was played before each performance in their repertoire: Sheridan’s The School for Scandal, Thornton Wilder’s The Skin of Our Teeth and Shakespeare’s Richard III; the pair were photographed alongside the First and Second Folios of Shakespeare in the State Library of NSW. Andrew recalled loitering at the stage door at Her Majesty’s every night hoping for a glimpse of the gilded couple as they got in their car, then scampering to the Windsor for a glimpse of the couple as they got out. One night, Olivier recognised Andrew and saluted his persistence - alas, Andrew was too starstruck to remember the ensuing conversation.

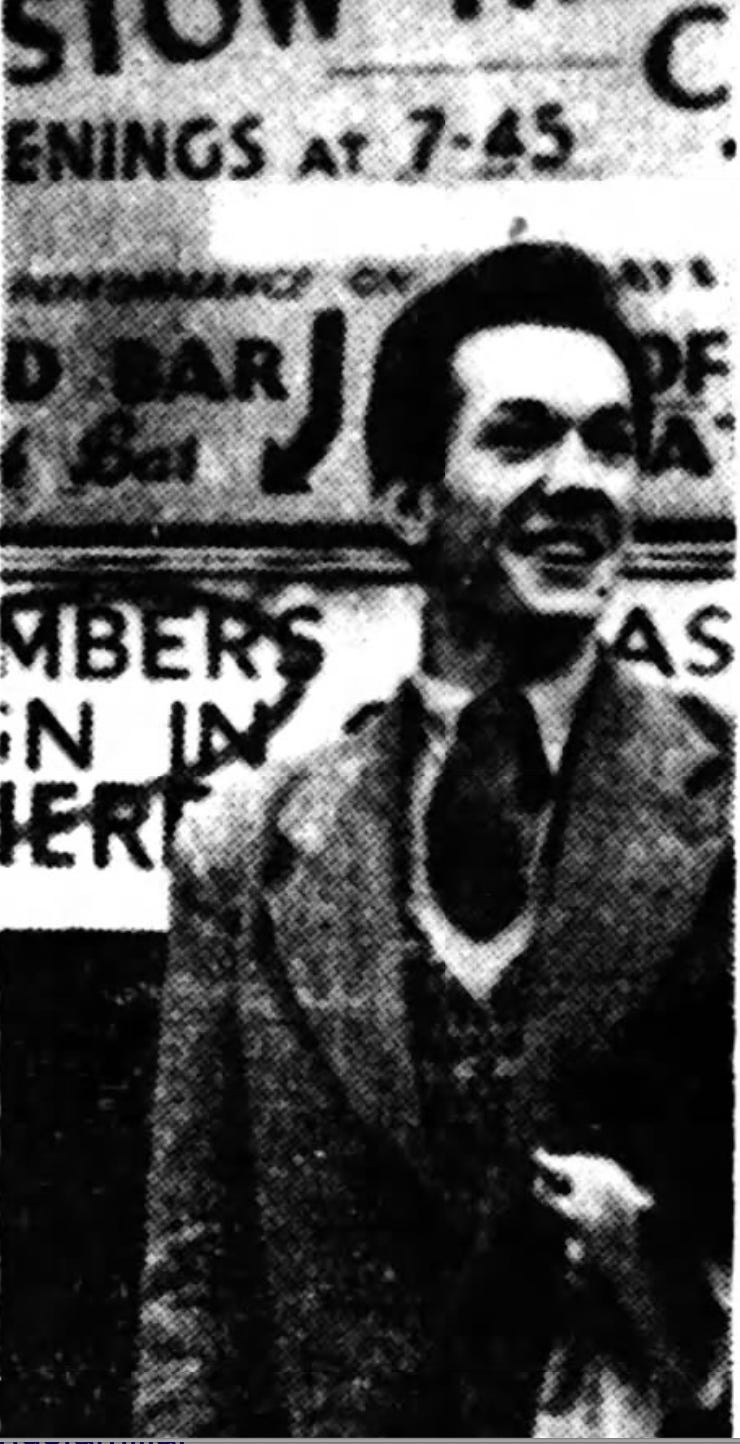

Bellew family lore is that John met Olivier and Leigh backstage, and urged him to come try his luck in the West End, as actor like Leo McKern and Jane Holland already had, and Peter Finch would - becoming, of course, Leigh’s lover. But London was to loom in John’s story in a different way. When I asked Andrew about Kenneth Cope [below], an ambiguous figure in The Girl in Cabin 350, his expression darkened. ‘I hated Kenneth Cope,’ he said.

Kenneth Cope, the son of a North Balwyn dentist, was training to be a dancer, although Andrew was disparaging of his dancing, and of his character: with strong enunication, he described him as a ‘practised homosexual seducer.’ Andrew recalled his suspicion when Cope asked for an introduction to John: ‘By this time I’d woken up to him. I said: “Not on your life.” ‘ But one night as Andrew and John walked up Collins Street to Cinders, Cope emerged suddenly, as if he had been lying in wait. The effect was immediate. ‘It was love at first sight, on John’s part,’ Andrew recalled. ‘And they began an affair.’

In The Girl in Cabin 350, I hedge around John Bellew’s sexuality. ‘Was John even entirely sure of his own sexuality?’ I write. ‘For all his savoir faire, John Bellew was still only nineteen, living at home and surrounded by peers negotiating their sexual preferences in an unsympathetic land.’ The newspapers later referred to him as Gwenda McCallum’s ‘boyfriend’. I inferred from his adjacency to the gay subculture of the performing arts that reporters were unsure of his sexual preferences because perhaps neither was he. Not until 1981, of course, would male homosexuality be legal in Victoria; a number of John’s acting contemporaries, such as Alan Rankin and John Craig were jailed for indecency; the likes of Frank Thring and John Alden hid in plain sight. Anne pitched in at this point. ‘My mother always thought that John may have been homosexual, and been unable to admit it,’ she said. ‘I think he was probably bisexual,’ replied Andrew. ‘And that Ken Cope was probably his first man.’

I had first become aware of Cope through a citation on Trove.

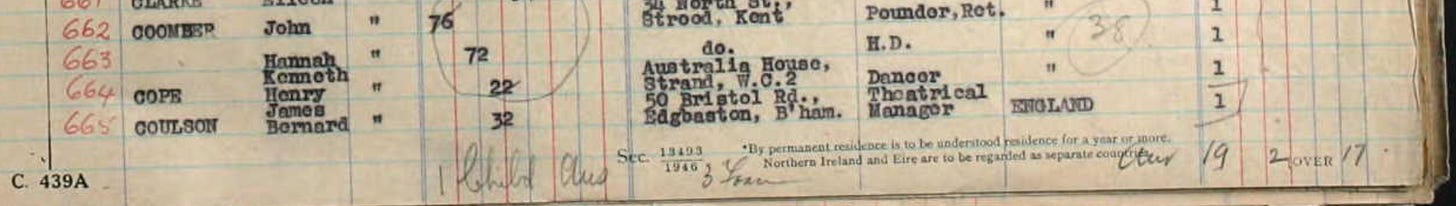

A FAREWELL party was given by Mr and Mrs W. H. Cope, of North Balwyn, for their son, Mr Kenneth Cope, a young dancer, who leaves soon for England to further his studies. Most of the guests were looking forward to the drama and ballet performance on Sunday night, which Mr John Bellew is giving for Mr Kenneth Cope in the Melbourne Repertory Theatre, Middle Park.

That evening would have been Sunday 18 June, the day before Cope boarded P & O’s Strathnaver bound for Southampton: he arrived six weeks later, listed as a ‘dancer’, giving his address as Australia House in the Strand.

Here Anne cut in. She remembered a dispute between John and Cope’s parents about the proceeds from that ‘drama and ballet performance’, which for a period subdued him. 1949 should have been a great year for both John and Andrew. Andrew, by now enrolled in arts/law at Melbourne University, won a critic’s award for his performance in O’Neill’s Ah, Wilderness. John was on the road, playing to big audiences in Thomas’s Charley’s Aunt, and planning to revive the Stokes brothers play Oscar Wilde in which he had earlier appeared for the Independent Theatre. Around this time, Andrew remembers, John invested in an exquisite houndstooth overcoat. He was a beautiful looking man.

Via his brother Peter, John had also encountered Gwenda McCallum, a teenage nurse. ‘Gwen was a jolly girl and we had some good times together before we quarrelled,’ Peter would later tell the press, rather grudgingly. ‘After our quarrel she became friendly with my brother John, and went around a lot with his companions, who were actors and the “arty” crowd. I did not see much of her during this period, but she appeared to be very attracted to my brother.’ Which may, of course, have been the cause of the quarrel.

At any rate, on the morning of 31 August 1949, the brothers Bellew left the Jolimont home they shared with mother Nell, crossing Treasury Gardens for the city, and separating about 10am. Peter later saw John outside the Hotel Australia in Collins Street ‘laughing and joking’ with a friend, Audrey Lovich, an actress for J. C. Williamson who also worked as cashier of Bourke Street’s Metropole Hotel. ‘He was in very high spirits and cracking jokes,’ Lovich herself recalled. ‘Whilst I was with him we were making plans for the weekend and he was talking to a person who was to be our host….He left shortly after 5pm and told me he was feeling a little tired and was going home to have an hour’s sleep before going to work in the theatre.’

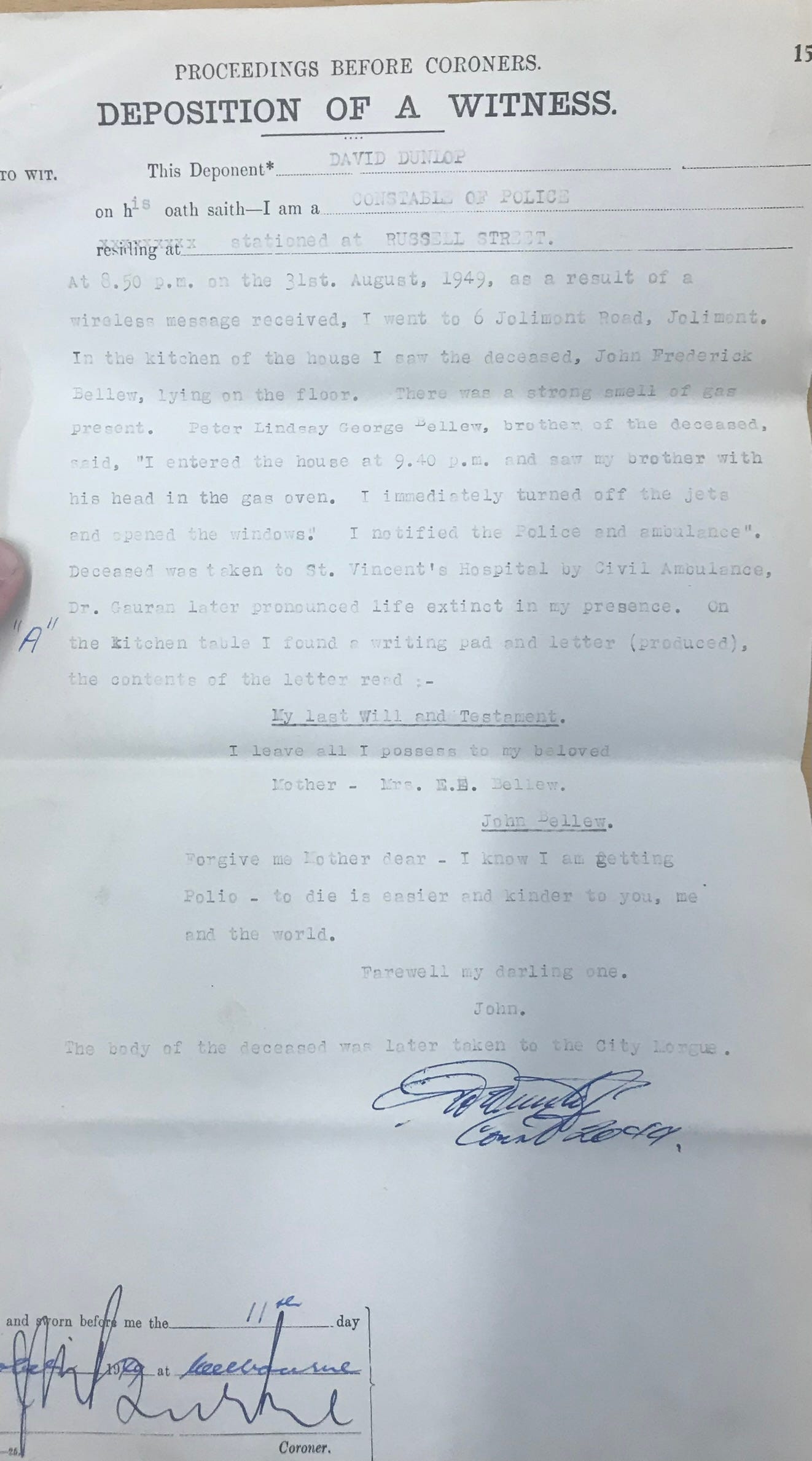

At some stage during the day, John rang Andrew. Andrew was not home. Andrew’s mother asked if John would like to leave a message; John said no. It was Pat Hoisfield who broke the news: Peter Bellew had arrived home in the evening, to find that John had gassed himself. The only clue as to his state of mind was a hastily-scrawled note, his mother the addressee:

My last will and testament

I leave all I possess to my beloved

mother - Mrs EE Bellew

John Bellew

Forgive me mother dear - I know I am getting

polio - to die is easier and kinder to you, me

and the world

Farewell my darling one

John

Nonsense, says Andrew: it was clearly an attempt to cushion the blow. Hoisfield, he recalls, told him otherwise: ‘John came home and found Ken Cope in bed with another man.’ The pair of them embarked on a journey to find John’s grave. They first went to the wrong cemetery; when they found the right cemetery, they found the wrong grave. Eventually, Hoisfield, dressed dramatically in black hat and cape, settled for scattering their flowers among the other graves. Then the sequel, which I chronicle in The Girl in Cabin 350. A week after John’s funeral, Gwenda lost her mother; two months to the day of John’s death, Gwenda disappeared from the deck of the liner Orcades. The police quickly drew a connection between the deaths of the two teenagers. ‘Grief, Drugs, Drink blamed for girl’s jump from liner’ was the Daily Telegraph’s eye-catching headline, with a touch of reefer madness thrown in.

Detectives believe that 20-year-old Gwenda MacCallum, who disappeared from the liner Orcades at sea last Sunday, may have been grieving for her boy friend, John Bellew, of Jolimont, who poisoned himself on August 31.

The police also think that Miss MacCallum had smoked cigarettes containing the drug marihuana. They believe that, under the stimulus of the drug and alcohol, she became morbidly remorseful over Bellew's death and jumped from the liner.

For her part, Joan tried to delink the pair.

I was with Gwenda and John many times. They were great friends, but I do not.... think there was any love affair involved. As far as I know, Gwenda never drank and was mostly interested in the theatre, which was also the interest of most, of her friends.

She smoked, liked good company, and I'm almost positive she had no quarrel with John. After John's death Gwenda was very upset. Then her mother died and she became very moody. She was obviously affected by the two deaths.

The theory I advance in The Girl in Cabin 350 is that Gwenda may have been pregnant to John; that John may himself have been cuckolded by Ken Cope provides an extra side to a tortured triangle. If Peter Bellew knew, he wasn’t saying: Andrew remembers, with disgust, that a week after John’s death, he saw Peter coolly dressed in John’s new overcoat.

Everyone copes differently with trauma. Andrew had his own at this time. In the three weeks around John’s death, he also lost his father, his grandfather and his aunt: he dutifully abandoned his studies to take over the family business in Chiltern. But he wonders still how things might have been different if he had been home when John called, and if Ken Cope ever brooded on the destruction in his wake. In a February 1950 interview in the Kensington and Chelsea News, Cope gave his address as De Vere Gardens in South Kensington, and expressed a desire to move on from the local Ambassador Dance Company to Sadlers Wells; in fact he would settle later that year in Malmo, where he commenced a career as a ceramic artist, and his partner for thirty years was the Swedish actor Folke Sundquist.

Both of them died in 2009; Peter Bellew’s widow Barbara died last year. That leaves Andrew and Anne as the last people on earth who knew John Bellew. But there we were yesterday at the Convent, with my girlfriend Janeen and with Andrew’s friend Lachlan, somehow back in the 1940s as Andrew remembered his friend and Anne her cousin, contemplating the mysterious social, historical, emotional and even astrological forces that had drawn us all together.

If you’re after a copy of The Girl in Cabin 350, drop me a line here.