What's Really Happening at the State Library of Victoria?

GH has some thoughts

Last Friday, the State Library of Victoria released a statement addressing what it calls ‘the false narrative’ around changes mooted by management. One reverberating paragraph instantly caught the eye:

Our founder Sir Redmond Barry imagined an ‘emporium of learning’, free and open to all. That vision continues to guide us.

Except the library had misrepresented its founder. Barry didn’t acclaim the library he founded as an ‘emporium of learning’. Instead, while addressing a librarians’ conference in London in 1877 about his library’s lending relationships with ‘Public Libraries, Mechanics’ or Literary Institutions, Athenaeums, or Municipal Corporations’, he credited these ‘distant relatives’ with ‘a desire to advance the great cause of education, which may be said to begin in real earnest when men enter on the struggle of life and resort to a great emporium of learning and philosophy, of literature, science, and art.’ Which is rather different to standing on a chair and declaiming: ‘I hereby declare this an emporium of knowledge.’

It was not the first time the phrase had been misappropriated - it had been rolled out in the Strategic Reorganisation Change Proposal presented to library employees last month, which many of us are now protesting. At the time, one of them politely emailed interim CEO John Wicks that the use of the expression was ‘a bit misleading in this context’; like a conscientious librarian, he suggested some more precise alternatives. Wicks, a Sydney accountant of limited library experience who took over temporarily when the contract of previous CEO Paul Duldig expired four months ago, did not acknowledge the message. Quibbles are for the little people, aren’t they?

I had a first hand experience of this attitude last week when, after articulating our protest in The Guardian, I was called by the library’s board president. Christine Christian complained that the document in question was merely a proposal, part of a negotiation. It had regrettably been leaked by unscrupulous persons. All was sweetness and light except for ‘four malcontented employees’. I asked her to name them. She declined. How was she sure there were just four? She would not say. I wonder, in fact, what workforce surveys of the library are telling her about staff morale. It is data that management is reportedly loath to share….

Christian complained I had referred to the board as ‘diversity hires’. I replied that I had levelled the opposite criticism, of a lack of board diversity - after all, wouldn’t one expect the board of a great library to have at least one, errr, librarian? By comparison, the council of the State Library of NSW features a member with thirty years’ experience of regional libraries, not to mention a well-known historian, a leading art critic, a young Vietnamese novelist, a successful lawyer with an honours degree in colonial art, and a successful businessman who collects rare books. The board of the SLV….well, it doesn’t. It is a board, as Emeritus Professor Judith Brett observed last week in The Australian, ‘without anyone whose lifeblood is reading and writing’.

Still, I am mischaracterising my encounter with Christian if I convey this as a conversation involving an exchange of views. I recognised at once the particular tone of wealthy and entitled Australia - all perfectly polite until someone has the temerity to disagree, to which it is completely unused. Then it’s not about persuasion, or seeking common ground, or discussing issues. Then it addresses you like a servant.

Anyway, at risk of repeating myself, the Strategic Organisation Change Proposal is a bonfire of banalities, of platitudes and jargon better suited to the prospectus of an IT start-up than a library: ‘Along with the rapid pace of technological change, we need to be flexible and creative, developing more streamlined ways of working to deliver the greatest impact for our communities…The Library recognises that to be a digital-first organisation in a fast-paced digital economy, we must invest in digital skills and capability.’ It claims as its mandate rising visitation figures, without at any stage presenting analysis of these users, their nature or their needs. My guess, indeed, is that a great majority of the library’s daily population are uninterested in the ‘fast-paced digital economy’; they simply want a congenial place to study and free wi-fi near their student accommodation. Which is great, by the way, but it means that their presence is no harbinger of the future, for they are clearly content with the library as it is. So it is nonsensical to invoke them in a campaign significantly deprioritising SLV’s capabilities as a research library.

The Strategic Organisation Change Proposal, in line with the pre-existing strategic plan, accents the library instead towards what it arbitrarily capitalises as ‘Compelling Digital Experience’; its hero is an ever-expanding ‘digital directorate’, created by Duldig although sounding like it was an idea of Philip K. Dick. Into this beckoning future, only ten of twenty-one senior librarians can be squeezed, on what’s cheerily called a ‘spill and fill’ basis, into a new ‘reference and reader experience branch’ - they do love the word ‘experience’ in this plan, for it appears twenty-two times.

Management prefers presenting the overall figures in a net sense - thirty-nine jobs lost and thirty-four ‘created’. But the effect must be understood cumulatively. Since a root-and-branch restructure in 2019 that essentially eliminated specialist collections librarians, the SLV has been haemorrhaging senior staff, from its rare books gurus Des Cowley and Nina Whittaker, to its senior exhibitions curator Carolyn Fraser and the capable corporate service director Sarah Slade who many feel should have been the last CEO rather than Duldig. Formerly chief operating officer of ANU, Duldig inspired little confidence in a majority of staff. He’s recalled introducing himself at a library leadership seminar, and being asked: ‘Why CEO? What about the role appeals to you?’ Said Duldig: ‘I’m at a point in my career where I would like to be peerless. I’ve done the CFO; I’ve done the COO. I’d like to make the decisions myself.’ Looks were exchanged in the room: the guy wants to run a storied collecting institution just because he wants to run something? Anyway, decisions he made.

At senior executive level, actual library knowhow is now so thin that SLV is fifo-ing a retired librarian, also from ANU, three days a week at unspecified cost. The chief operating officer, like the CEO, is acting in their post; there is no head of collections; the head of collection access role is to disappear; the branch head role for collection development has been vacant for two years; the library sector engagement area, which offered highly-regarded training services to public libraries across the state, has been slashed; opening hours cut and heritage retrievals slowed during COVID have never been restored; the gorgeous heritage reading room, in fact, is to be closed over Christmas for unexplained reasons. Oh, but they have a talking boot….

I could go on, but the nub is this: there’s a widespread impression that core library functions have been allowed to atrophy at the expense of modish digital exhibitionism. And the idea that the further loss of experienced library staff can be mitigated by the creation of new mainly technological positions is like a hospital retrenching surgeons but hiring the same number of nurses and claiming there will be no net change in medical personnel. There are also disturbing reports from within SLV of a souring culture - of insular top-down management, of stealth restructuring, of bullying, of cronyism and of censorship. That last episode not only did the library great reputational damage, but internal damage too, exposing blameless library staff to deplorable abuse from the public. They would be entitled right now to BOHICA syndrome.

So, yes, just the time to be embarking on another holus-bolus reorganisation in which everyone takes a step to the left and gets a new title where they aren’t shown the door! Because change is good, prates Christian in this self-justifying ramble - a version of a speech she trotted out to potential donors last week. Change is essential and change is brilliant. Who could be against change? Only a stick-in-the-mud like Helen Garner, apparently - a gross impertinence from Christian, given how Garner ennobled the library by writing Monkey Grip in the La Trobe Reading Room.

Of course, Christian can’t help but travesty her critics. For my part, I certainly don’t pine for the library of forty years ago. When I first visited, Phar Lap was in the entrance foyer, and I hardly wish it back; the library was epic, but also moribund, the result of decades’ underinvestment, a demoralised workforce, a deteriorating infrastructure, and the confusing mix of its mission, for the site also doubled as Melbourne’s museum. But what we learned then is that there is change and change.

Because forty years ago the Cain government appointed the CEO of the State Bank, Arnold Hancock, to lead a committee considering the library’s future. It was composed of businessmen and management consultants. One of those who drafted our open letter to Christian last week, Emeritus Professor Graeme Davison, recently recounted the Hancock committee’s deliberations in the Victorian Historical Journal:

They [the Hancock committee] approached the library much as they would a failing company, looking for assets to strip, redundant services to slim down, curtail or outsource, slow-moving stock to be liquidated, and antiquated technology or staff to be replaced by new. It noted that some books in the collection appeared not to have been used for some time—why not sell them off to finance new development? The library had microfilmed many of its old newspapers, so why bother keeping the hard copies? Amidst all its talk of service delivery and innovation, there appeared to be no concern for the heritage value of the collections, many of which, of course, had been donated in expectation of their preservation in perpetuity.

The State Library Development Council, a coalition of scholars, librarians, publishers and conservationists led by the architectural historian Miles Lewis, was formed in response. Its far more expert report, informed by actual inside knowledge and wise external counsel, put timely chocks beneath Hancock’s corporatist chariot. Then, with perfect timing, the State Bank collapsed, casting Victoria into the slough of despond, and plans for the library into disarray. It was the old museum, in the end, who moved out; and it was a new casino that in large measure underwrote the restoration and rejuvenation of the library. A paradox that eludes Guy’s generally perceptive analysis….

Anyway, one might observe, each generation imagines change through whatever it exalts, however temporarily. Forty years ago, big business was felt to have all the answers; now, it is technology. What Graeme continues to say in his essay is germane:

Suppose, for a moment, all the printed books, journals, pamphlets, pictures, manuscripts, and ephemera in the State Library were digitised and the images were available to readers via the worldwide web. That’s not an entirely fanciful prospect. Some might even consider it a welcome one. The reader in Wodonga or Portland would then be as close to the library as the one in Carlton or South Melbourne. Suppose, further, that during one of those economic downturns that periodically afflict the state, a frugal treasurer, a digital native who has never read a book herself, looked down from Spring Street and asked: ‘Do we really need that big building on Swanston Street any more?’ Surely we could just store all the data in the cloud, recycle the collection as waste paper, sack most of the staff, bulldoze the building and make space for some more student apartments? What would be lost in such a transaction? I can imagine a number of responses to that question. What if the big digital collection in the cloud is corrupted, hacked or otherwise lost? Can a digital image provide all the information that is stored in its original? And then there are the nagging epistemological questions: is ‘information’ the same as ‘knowledge’, and is the ‘virtual’ a substitute for the ‘real’? A library is not just a collection of books, or a database of digital information; it is also a place where we read in the visible presence of other readers, and with access to the help and advice of expert librarians who can guide our inquiries. With each step from the real and original towards the digital and virtual, we are both progressing and regressing. When we say, as the library often does these days, that the domed reading room is ‘iconic’, we need to ask ourselves what is it an icon, or symbol, of? Can the symbol remain potent without its physical counterpart—the collection of books and readers—gathered under it?

Nobody, of course, is calling for the ‘dozing of the dome - yet. But the Strategic Reorganisation Change Proposal is clearly a stalking horse for further change, such as the throwing open of the La Trobe Reading Room to ‘immersive cultural experiences’, for which SLV is seeking a cool $45 million from donors, and the uprooting of the beloved arts library, trampling Joyce McGrath’s decades of dedicated handiwork. While the board are transfixed by annual visitation, which in the latest annual report they excitedly put at 2.8 million, the same report reveals that frontline staff in that time dealt with more than 52,000 queries, a forty per cent increase. Funny time to be pruning the public-facing personnel best acquainted with the collection, eh?

There is also a subtle denigration going on here. Christian refers to the minority who make active use of the collection - and it has always been a minority - as ‘people who use those services’. It’s as though we are a bunch of obscurantists, and I’m surprised she didn’t deride us as ‘elites’. Yet we’re a huge and diverse body. There was star power in the signatories to our open letter from Garner, JM Coetzee, Nick Cave, Paul Kelly, Geraldine Brooks, Kate Grenville, Trent Dalton, Tim Rogers, Dave Graney and Peter Fitzsimons, but you’ll also find artists, graphic designers, genealogists, architects, economists and judges. Did the writers of the Strategic Reorganisation Change Proposal solicit their views? Because where is the evidence? I mean, if you purport to value an ‘end-to-end, customer-centred focus on accessing the collection’, you might want to know about who you’re helping. Here’s a tip: they may not see themselves merely as ‘customers’….

The idea of ‘moving with the times’ is always alluring. But what if the times are not good? What if the times involve knowledge and veracity trading at a worsening discount to noise and ignorance? Then, for a library, founded under an act of parliament to ‘ensure the maintenance, preservation and development of a State collection of library material’, might it not be expedient to lean, at least a little, against the times? Is it not a moment to double down on the integrity of the library’s holdings and the expertise of its handlers rather than fall in with the march of post-literacy and information inundation? How will your digital vanity projects serve the posterity which the library as custodian is entrusted? This, by the way, is not an argument against technology or digitisation per se, which when not vacuously experiential and designed to be useful are hugely valuable. They’re so valuable, in fact, I’ll use them right now to whistle up a favourite photograph of the State Library’s Queen’s Hall, taken in 1859 by Barnett Johnstone.

The photograph places the inaugural state librarian Augustus Tulk among workmen involved in the building’s construction posed for the occasion. It’s probable that the latter’s literacy was basic, or even non-existent. It is, then, an aspirational image, for Barry, in the library’s 1865 supplemental catalogue, envisioned a place that catered to ‘all ordinary readers, the wants of men of every profession, trade, calling, and occupation, the desires of those who indulge in the pursuit of polite literature and of every branch of human inquiry.’ Perhaps these workmen did not understand completely what was in front of them; but, with time, and care, and patience, they might, and their children have a better chance than that. We should be concerned that without experienced guidance, a new version of this image awaits: a library where people stare at materials they barely understand if they can even find them. Because if you insist on claiming that Barry’s ‘vision continues to guide us’, it may also be worth consulting the stanza of Goethe’s Faust with which he prefaced the above:

Some sparkling showy things got up in haste,

Brilliant and light, will catch the passing taste;

The truly great, the generous, the sublime,

Wins its slow way in silence.

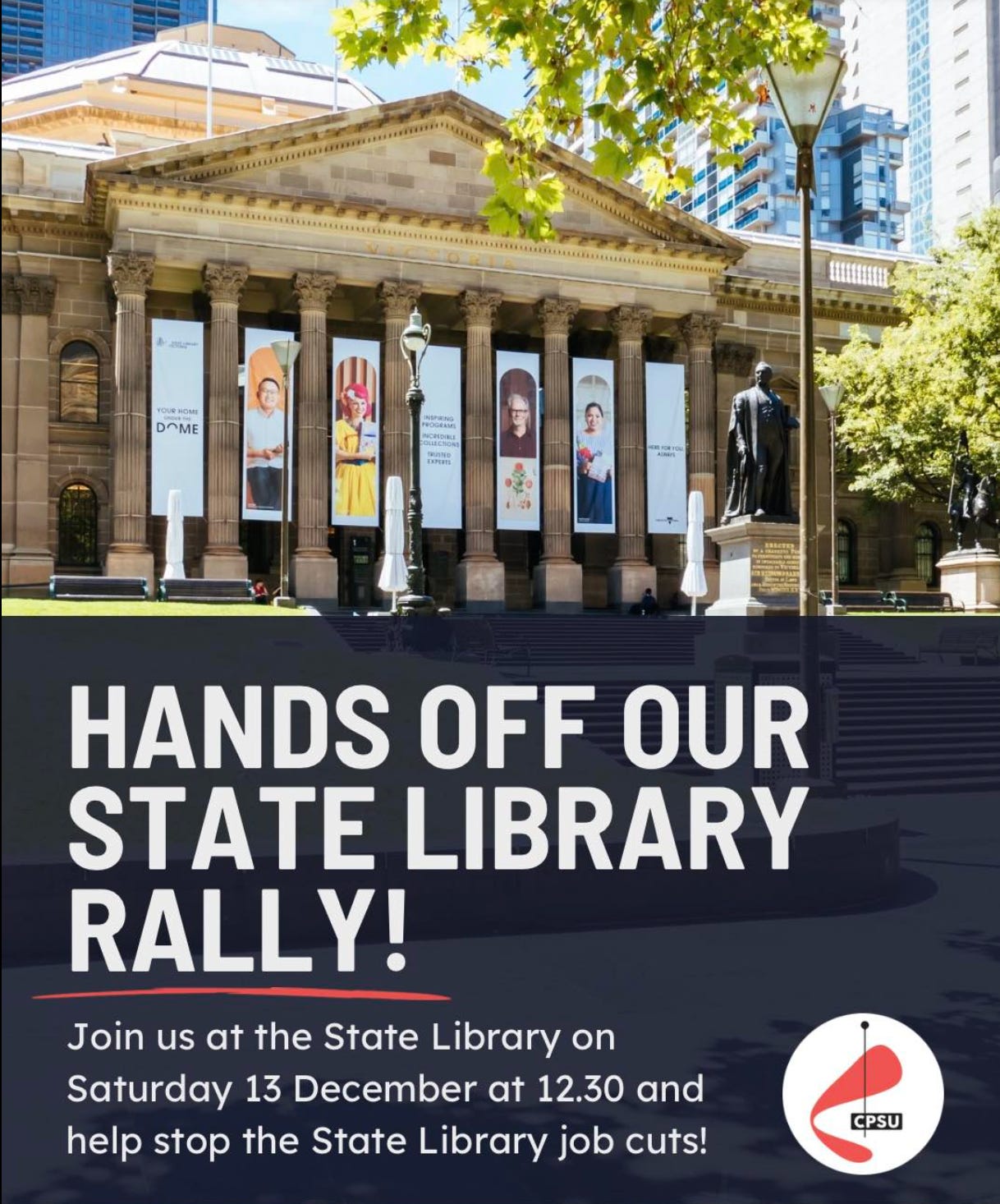

So this Saturday, if it doesn’t sound too meta, there will be a rally at the State Library of Victoria about the State Library of Victoria. It will start at 12.30pm. And here’s what we think the minister for creative industries, Colin Brooks, should do. These changes should be paused until they are properly interrogated. Given that she was reported to be ‘preparing to end her time at the State Library of Victoria’ in June, Christian should do so. That would expedite Wicks’s succession by a permanent appointment with library credentials. It is the board who should then be ‘spilled and filled’, to embark on a vision for the people’s library prepared after proper consultation with actual people. Oh, and the bone-headed decision to kill off Mr Tulk should be reversed. That would be organisational change we could all get behind.

Anyone else thinking Gids would be a perfect Board Member of the Victorian State Library ..??

Ahh, GCJDH. A really important piece. Totally captivating. It speaks to situations well beyond libraries.

And it really is the rallier's rally piece. Tremendous call to arms.

I'll be with you in spirit.

I find it easier here in the Principality of Krondorf, head happily buried in the sand. Thousands turned up to the Barossa Christmas Parade (think 1968) and our libraries matter and are valued. Vigilance is required, of course. Please keep a lid on the secret of Barossa Life.

And, as for the MCC Library?