Who Was Wallace?

GH on how a hundred-year-old murder case got under his skin

It started a couple of years ago, with a question from my daughter C. Who, she asked, was the world’s oldest prisoner? Someone, I anticipated, consigned to a gulag, or penned up on a southern death row. But the Guinness Book of Records had a surprise in store.

Suddenly, a weird patriotic pang - not only Australian, but Victorian! Still, really? A man lingered in captivity almost to the age of a hundred and eight without trial, without review, without protest, and without ever giving an account of the crime of which he was accused? Because from the moment Wallace was taken into custody a hundred years ago, he betrayed nothing of his origins or his circumstances.

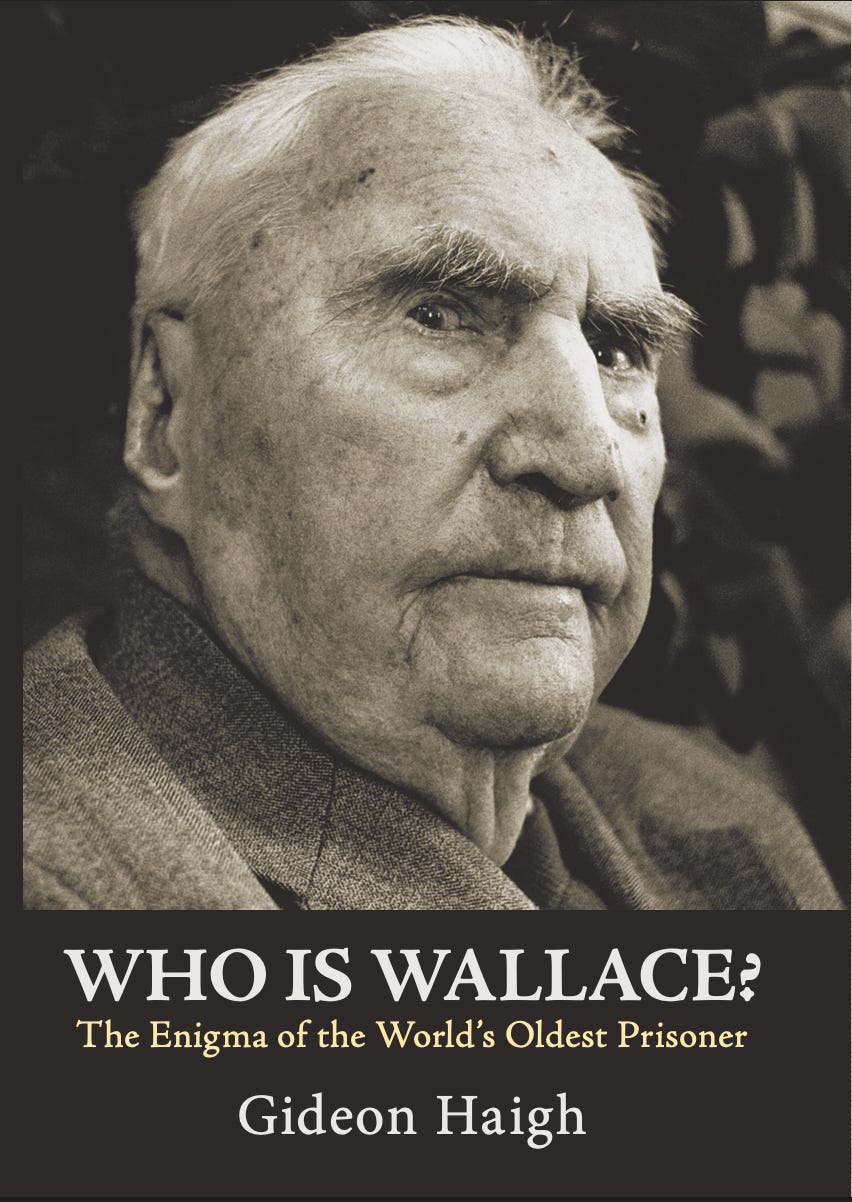

So, what to do? Is it possible to write a book about someone so inscrutable so long, a man detained at one governor’s pleasure who outlived the next eight? There was only one way to find out, which was to try. And what do you know? You can.

Which is not say that it was not extremely difficult, and also about as far from a mainstream assignment as you can get - in fact, I elected from the get-go to publish Who Is Wallace? using my kitchen table imprint, the Archives Liberation Front….

…..using the colophon that C designed for me five years ago.

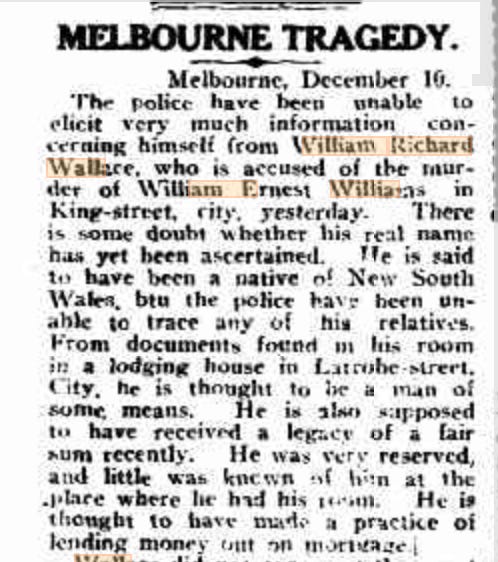

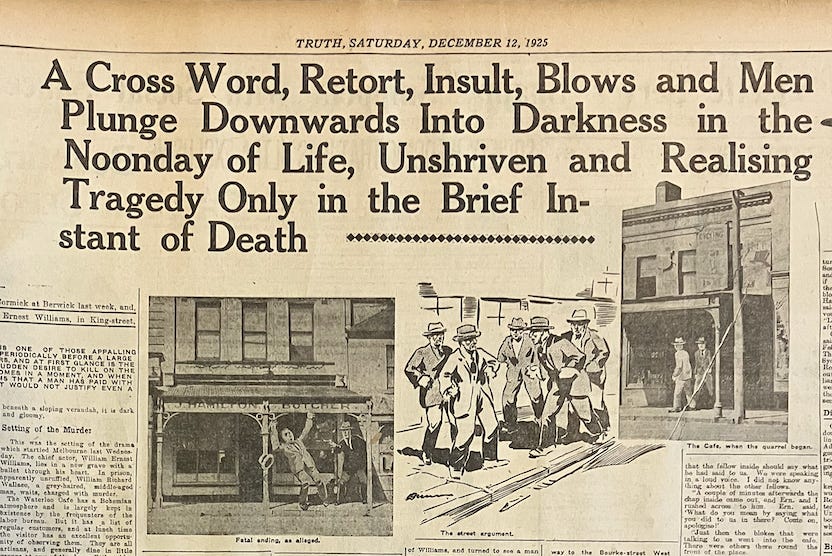

Here’s the guts of it. On 9 December 1925, two young men, Jeane McRobertson and Ernest Williams had finished lunch in a cafe in King Street when the former lit a cigarette. Another diner, Wallace, complained. Harsh words were crossed - McRobertson’s American accent added an edge to the exchange. The pair left, but lingered outside, complaining about their anonymous antagonist, spoiling for a fight. When the diner emerged, McRobertson and Williams were there, with others, and a brawl ensued in which the outnumbered Wallace pulled a pistol and shot Williams

All in a day’s gun crime in the lawless streets of 1920s Melbourne. But Wallace was not your average suspect. On remand at Pentridge, he began complaining that he was the victim of unidentified conspirators with impenetrable plans to defame and extort him. When he was offered the chance to give evidence, he refused. Two doctors submitted medical reports - one paragraph each - insisting that his paranoia was incurable.

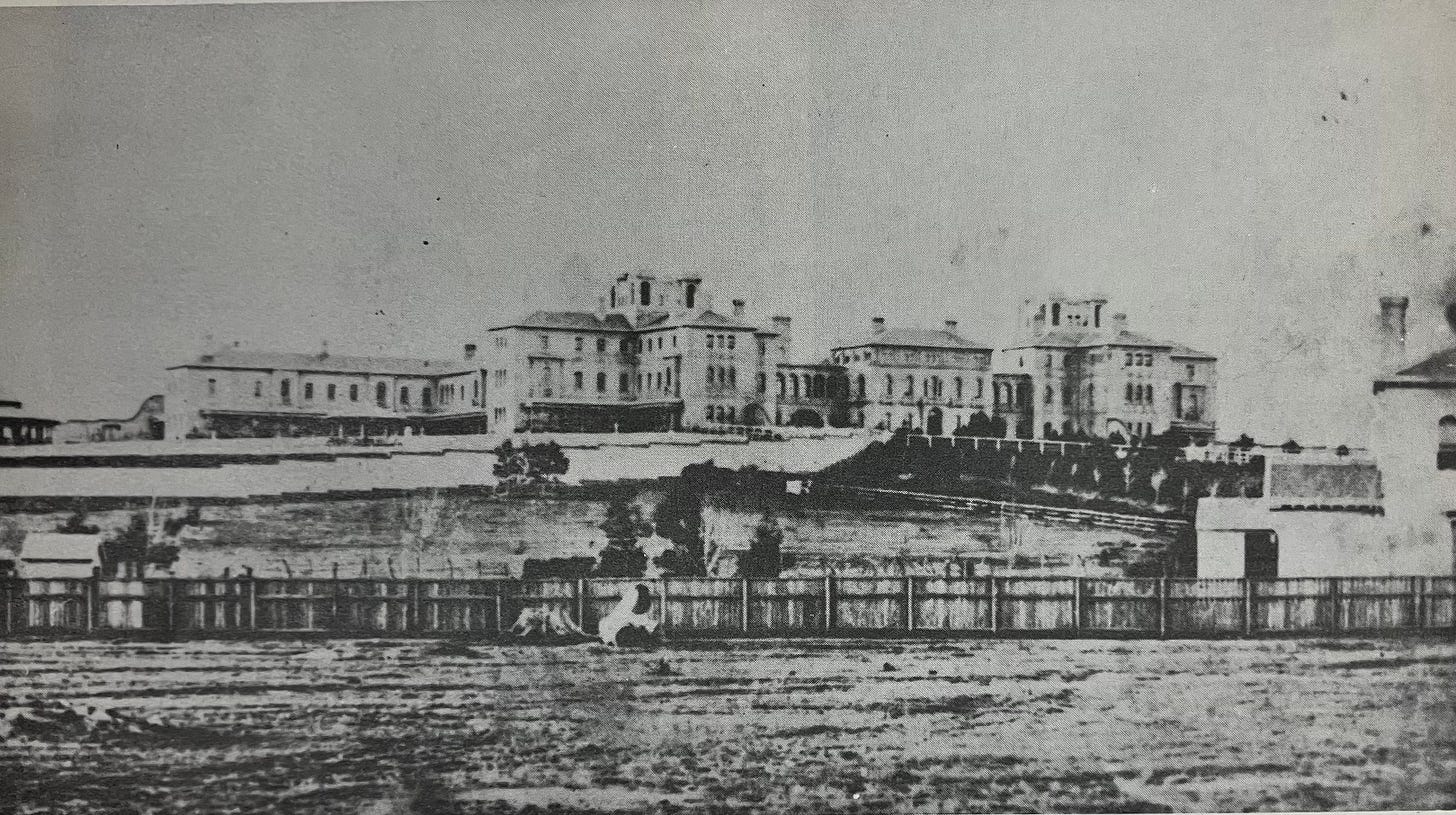

That was enough to have him committed to J Ward, a converted jail in Ararat for the ‘criminally insane’, where he languished until 1962 until he was transferred to the main hospital - what had been completed a hundred and sixty years ago as Ararat Asylum. And, errr, that’s it. Except for everything else.

So who was Wallace? After months of genealogical ferreting, I was able to locate a couple of living relatives. With their consent I hit the health departments in Victoria and New South Wales with freedom of information applications - and a man who spends so much time under the surveillance of the state generates a lot of public records. For the intrepid researcher, in fact, Wallace had left a little trail of bread crumbs - in survey maps, land registers, council minutes. He had even served in the Boer War - of which, mirabile dictu, he was Australia’s last survivor.

But after settling to a successful farming career near Dorrigo, his life took a wrong turn. He began to believe he was being followed; he suspected his family’s involvement; and when he ended up in the asylums at Kenmore and at Gladesville in New South Wales, the so-called ‘Master in Lunacy’ sold him up. That left him rootless and anxious. He tried to disappear; but, as he saw it, they found him, and would not let him go.

Because Bill Wallace’s story is also that of Australia’s mental health ‘system’. He received no treatment whatever; his taciturn gruffness deterred all attention until it was too late for any outcome other than continued incarceration. He was not, in fact, uncommunicative. I found in the undifferentiated administrative files of Ararat Mental Hospital at the Public Record Office a cache of letters that Wallace wrote to Victoria’s Inspector-General of the Insane complaining in granular detail about aspects of his incarceration - it was, inevitably, in the last of a score of huge boxes I rummaged in on spec, unheralded and unexplained. In them, however, nobody seems to have taken the slightest interest - the predictable outcome of a regime that was custodial rather than therapeutic, designed for the convenience of the state not the welfare of the ill.

J Ward was every bit a bluestone barracks, reserved for those perceived Victoria’s most dangerous with the meagrest possibility of release, overseen by staff indistinguishable from prison warders. The Ararat Asylum, renamed Aradale in 1958, was a grand Victorian pile, which lumped together all the state’s unwanted, from disabled children to epileptics, from men with florid psychoses to women with postpartum depression. Between them lay the town itself, with an ambivalent regard for these institutions - objects of fear and concern, but also providing many jobs, on good terms with handsome perquisites.

At around the time Wallace transitioned from J Ward to Aradale, perspectives were beginning to change. Governments and health officials were losing faith in dark satanic mental institutions. Drugs were emerging that if they did not cure mental maladies at least quietened them. There was a rare alignment of humane and economic instincts - would it not be better, and cheaper, to throw open the asylum gates? So it was that Wallace became the (almost completely) still point in a (barely) moving world, even as Ararat, with a stake in their survival, dug in against reform. Wallace became, perversely, both an advertisement for the old system and a condemnation of it - the great survivor and the great victim.

When Wallace turned a hundred, he was feted by politicians and officials; when his case was taken up by newspapers and on television, he received sacks of fan mail.

Who Is Wallace? is my fifth foray in the last decade into true crime, a genre full of possibilities seldom explored other than cynically. And so it is also another attempt, in some small way, to buck the formula. Certain Admissions was written from the perspective of the elusive accused; A Scandal in Bohemia concerned the victim, her adventurous life and evolving afterlife; The Night Was A Bright Moonlight and I Could See a Man Quite Plain was chiefly about the milieu, the phenomenon of the remittance man and the life of the frontier; The Girl in Cabin 350 ventured into the ambiguities and lacunae of the missing person. At the risk of overexplaining, the subject of Who Is Wallace? is punishment - the open-ended sort where the prisoner is a patient and the patient a prisoner.

Anyway, there’s plenty to go round, and I reckon you might enjoy it. If you think so, deposit $50 in my account (bsb 733152, acct 525322), let me know your address (gideonhaigh@hotmail.com), and a signed copy of Who is Wallace? will be on its way. ‘Dad,’ C said the other day. ‘You don’t have have to write a book about everything that interests me.’ But it’s hard not to when what interests her is so…. interesting.

I have read a couple of your previous books- the one about the cabin and (sorry) I forget the name of the other- set in Melbourne (useless clue!). So I’ll do the financial side for this one. Congratulations on your hunt through sources/references, not only in this book but for so many other articles. Usually on cricket. I admire your search for the truth - it is a journalistic skill that is fading into total oblivion. And it is a gem worth more than the Louvre heist.

How about that Truth headline. That’d generate a few clicks.