A 9-year-old boy saddles his pony for an extraordinary journey

PL's book on the Sydney Harbour Bridge has been published in a new edition and Et Al is running an extract

Here, in the void left after events in Perth and Brisbane have been sashimi-sliced down to the last fishy subatomic particle, maybe it’s an opportunity to consider something else apart from how bad England were and how good Carey, Starc, Smith, Neser, Head & co have been going.

Pardon the indulgence here, but that something else is the latest edition of my book The Bridge: The epic story of an Australian icon, which is back on the bookshelves.

First published in 2005, the book about the construction and life of the Sydney Harbour Bridge has had a number of iterations; the original (OG) hardback, a paperback version of that, a 90th anniversary of the opening hardback and another paperback in 2022, both with updated jackets, and now there’s a new paperback edition.

I’m proud of this book. The illustrations and photographs, edited by Sue, are fantastic, the design of the first was a work of beauty and an extraordinary achievement by Allen & Unwin, given the circumstances (a story for another time).

Gideon and I ran into my old friend Sue Hines at the recent Phillip Island Festival of Stories. Sue was the former Group Publishing Director at Allen & Unwin who came to me with the idea of the book. She was also the instigator and publisher of Blood Stain and Barassi, both of which remain in print.

Sue Hines knows her stuff.

Retired now, she said to me at one stage over the weekend, that people are wrong to call this book a history, asserting instead that it’s a biography of a bridge. That sits well.

This time last year in a post on Cricket Et Al, I touched on a unique character in the book when writing about India’s young star, Yashasvi Jaiswald. The story of Lennie Gwyther, a child in his ninth year who rode his horse, Ginger Mick, from a small farm in Gippsland, southern Victoria, alone through the high country to Sydney to be at the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, is one that has stuck with me over the years and grown legs.

To that point, Lennie had only been a side note in history. I was determined to add flesh to his story. With Sue on the maps and the school-age kids in the back seat of the Camry wagon, I traced his route through the snowy mountains back country, stopping in libraries and historical societies to see if there was mention of his passing.

And there was.

His journey to Sydney took 33 days and captured the attention of 1930s Australia. People rode out from the small farms to meet the boy and by the time he got to Sydney, crowds had gathered in the CBD to catch a glimpse of a lad who one letter writer to the papers believed “was, and is, needed to raise the spirit of our people and to fire our youth and others to do – not to talk only. The sturdy pioneer spirit is not dead …”

I was also fortunate enough to get to know his little sister, Beryl, a wonderful older woman who told me stories of an older brother who built a motorised washing machine for his mum and a land yacht for his siblings. Lennie was building a boat in the backyard of his suburban Melbourne home which he wanted to sail to Tasmania when he died. I visited the farm where Ginger Mick is buried and spoke to had afternoon tea with his inlaws on the next farm.

I’ve always said that Lennie’s story should be taught in schools. That it should be part of modern Australia’s folk history.

Since publication, Lennie has been commemorated in songs and in a number of children’s books. A glance at the internet just revealed a surprising number of attempts to retell the story in one form or another.

Leongatha erected a magnificent statue of him and Ginger Mick on the outskirts of town some years ago, and the ABC Conversations has replayed the interview I did with Sarah Kanowski regularly.

I think word is spreading.

I’ll run the chapter below, but if you’re out driving, the interview is a good way to catch up on Lennie’s remarkable story.

PS: You can order a copy of the book here

Lennie Gwyther’s great adventure

(an extract from The Bridge by Peter Lalor)

Our narrative finds another hero in a nine-year-old Victorian boy who packs his swag and saddles up a horse called Ginger Mick for a solo journey to see the bridge opening.

Here’s a plump little lad on a plump little pony — Leonard Gwyther, who rode all the way from Gippsland or Switzerland or somewhere to Be With Us on this Great Occasion.

And here, striding along as if they didn’t give a damn for anyone, are a hundred ordinary blokes. They are in this galley because they helped to build the Bridge, and that seems a pretty good reason why they should procesh [sic].

The Bulletin 23 March 1932

LENNIE GWYTHER is riding out into the Australian morning, a hero on a horse, a child of the nation as it imagines itself: young, strong, adventurous and carefree, confident but not cocky.

In the months ahead he will be fêted and celebrated; invited into the halls of parliament and onto the elegant balconies of municipal town halls. The talkies, as they still call them, will set out to interview the monosyllabic nine-year-old and pressmen will record his feats in language reserved for explorers and conquerors. Lennie’s quest will make the news in Melbourne, Sydney and London. Crowds will line the street as he enters towns, thousands of eyes will rest on his back as he pushes further along, carrying their excitement and focus, but today, in his hometown of Leongatha, people barely have time for a curious glance as they pass. Everybody has something else on their minds.

Lennie sits and waits on his horse, Ginger Mick, near the showground, his short, skinny legs hanging, his thin lips quiet. He waves away a fly and whispers a few words to his anxious mother, who has the three little ones to control and is only too well aware of the fact that the son sitting above her on his pony will soon be out of her control and sight for too long.

Still, his father, known as ‘the Captain’, has said the boy can go and that is that, no matter what his mother or neighbours say or think.

Lennie has a distant stare. He has heard the bridge’s call. His nine-year-old engineer’s soul hears her straining against the bedrock of Sydney sandstone, hears the heavy metal cacophony of her labour and now he must go to pay homage to the idol.

Today, 3 February 1932, is Show Day for the small farming community nestled into the rolling hills of South Gippsland, almost 1000 km south of Sydney.

From the early hours they’ve been riding into town, down from the La Trobe Valley and up from the windswept Victorian coast. As the morning sun announces its harsh intent people swarm toward the recreation reserve, keen to find a place to tether the horses and a shaded picnic spot. Coming along the road the families are alarmed to see the whole area burned out by a grass fire.

It’s been that sort of summer. Every time the wind comes up from the north there’s the unnerving smell of smoke. At least the fire will have driven the snakes from the grass.

Despite the drought and the Depression, the show is almost as big as last year’s, which was the best on record. Livestock entries are nearly as high as in 1931; in fact there’s more poultry, fat cattle, swine and dairy produce than the year before. The ladies of the district have been working hard too, with 169 entries in the needlework display and a record fourteen entries in the art division. Stewards from the Agricultural and Pastoral Society spent all of yesterday placing exhibit tickets on the jams, scones, cakes, embroidery and the like.

Fortunately, the exhibition hall survived the fire. Word is that the blaze was started accidentally by a showman camped on the reserve. Fanned by hot winds, it spread quickly and almost consumed the buildings and animal pens. The local fire brigade arrived just as it threatened to leap the road and destroy the buttery opposite.

Lennie would usually be among the first down to the reserve. He and Ginger Mick are regular competitors in the horse riding events and they have a few blue ribbons to show for their efforts around the district. Ginger Mick is well rested and ready for a bit of sport, but today something else is going on and he’s not quite sure what to make of it as he shifts and twitches in the morning heat.

It’s going to be a long day for the rural community. At sunset there’s a special picture show in town with the ‘handsome, debonair, charming’ Edmund Low starring in The Matrimonial Problem at the Memorial Theatre. Later, a five-piece orchestra will take to the stage at the Memorial Hall for a good old knees-up.

The Great Southern Star says the dance will ‘terminate one of the best entertainments seen locally for some time’.

There’ll be bleary eyes in the milk shed tomorrow morning.

The paper, which is published every Tuesday, has been full of handy details, telling the women that hot water will be provided on the reserve so nobody needs bother about boiling their own billy, which was probably how the showman started the fire. There’s news that the Water Trust has imposed restrictions, banning the watering of gardens on Mondays, Wednesdays, Fridays and Sundays. Reading through the long columns as the day takes shape, visitors learn that the Leongatha shoemaker has bought a mechanised stitching machine that will allow customers to have the soles of their boots re-stitched while they wait.

There’s news from New South Wales too, where the Premier, Mr Lang, has been denied a £500,000 loan from the federal government after the Loan Council also rejected his requests. That will get them talking. The whole of Australia is watching the controversial

Labor leader who has defied calls to pull in his belt. At a time when debt, public or private, is considered almost sinful, Lang is the most sordid of characters. The Leongatha council is wrestling with the vexed problem of feeding the unemployed. It gnaws at the capitalist heart to hand out welfare to the needy, a practice which degrades the human spirit according to some civic and religious leaders.

Australia is as uncomfortable with borrowing money as it is with feeding the unemployed and today the paper has printed Section 9 of the Unemployment Relief Amendment Act 1931, which details the sort of work that can be demanded of the jobless and homeless who wander into districts, eyes downcast and hands out.

These wandering armies of shamed men can be made to maintain parks, repair fences and municipal properties, destroy weeds, dig ditches or carry out foreshore improvements.

The trade union movement strongly objects to the unemployed being forced to work. It takes precious jobs from the employed and in most Labor-dominated areas ‘susso’ is handed out without such demands.

The Depression has not bitten so hard in the country, but in some parts of the cities, particularly Sydney, 40 per cent of the men are out of work. Every day thousands queue from the early hours of the morning in the hope of getting a bit of work here or there. Those with jobs have had their days cut to share the labour around and one employed man or woman can often be found supporting the families of his immediate family.

At least today, with the show on, Leongatha can think about something else.

And Lennie?

Well, buried in the Personal Column of the local paper, below a story about James Jarvis who suffered internal injuries after his horse stood on him in town last Friday, is a passing mention of the local lad and his restless pony:

Feats of endurance in men are often quoted, but a feat by a lad of 9 years of age is about to be made. We refer to Lennie Gwyther, son of Captain Leo Gwyther and Mrs Gwyther, of Leongatha South. This youth has been invited to spend a holiday with friends in Sydney, and he intends to make the journey on the pony he has used to ride to school daily. His idea is to be present at the opening ceremony of the world’s largest bridge in March. The friends of the parents will wish Lennie every success in his undertaking.

Rural Australia in the 1930s might have been another country, but even then the idea that a nine-year-old boy could ride alone on his horse 600 miles to a distant city raised an eyebrow or two.

Not least because it was Sydney he was headed.

Sydney was a strange concept to rural folk; they had a sense of mistrust about any city, but Sydney was a special case. In 1932, it hadn’t been that long ago that the plague had broken out among its prostitutes and sly grog shops. There was a sense it had never lost its convict stain and now its socialist Premier, Lang, was always in the news, as were its soup queues, militia groups and sinister urban crime. The almost-finished Sydney Harbour Bridge was the only positive news they ever heard from up that way. Even the old farmers were impressed by the stories and pictures that made it into the Victorian papers.

The bridge was assuming its own significance in the early moments of the Australian historical narrative. If men like Lennie’s father, a decorated soldier, had proved themselves the equal of anybody at killing and dying on foreign shores, the bridge spoke of a different pride and competency in the adolescent nation. The biggest bridge in the world. Built by Australians. Our engineers are as good as any, the papers said. Our workmen brave and industrious. Our future bright. Our Bridge.

At last this threadbare antipodean population was starting to make its mark and there could be nothing more permanent or impressive than this engineering masterpiece of the machine age that would carry more trains and trams and buses and cars than any built in the more civilised parts of the globe.

The Sydney Harbour Bridge was already seeping into the consciousness; it was something to be compared to the Eiffel Tower, the Pyramids of Egypt and the Great Wall of China. It was a celebrity marriage of the symbolic and the functional.

To be alive during the construction of such a structure was an honour and it was difficult not to be caught up in the excitement.

And the Captain’s son was making his way to Sydney to see the Sydney Harbour Bridge and that was something too. Even as the Leongatha locals wondered about the sense of it they couldn’t help but be quietly impressed by the determined little boy and his pony.

‘It is the first occasion known to this paper where a Gippslander has made the trip to Sydney in the saddle. So the Leongatha lad must be regarded in the light of an overland pioneer,’ the Journal (‘The Paper with a Punch’) told local readers on the following Monday. The Captain’s chest swelled with pride at these reports and in the coming months he became a reliable source of information to journalists who took up his son’s story. Lennie was a chip off the old block. A little soldier and man in the making.

In the days that followed he was celebrated in extraordinary terms. ‘A typical bush lad,’ they said in the Cooma Express, ‘unassuming and casual, and tremendously interested in machines and engines.’ ‘A real Aussie with that inborn pluck, prepared to tackle anything,’ they sighed in Queanbeyan. ‘The good pioneering spirit which has always sent men out regardless of the dangers ahead is very much alive in this sturdy Australian boy,’ the Goulburn Evening Penny Post opined, while a letter writer in the Sydney Morning Herald saw in Lennie the ‘spirit needed... to make a nation’.

Poor Lennie had no idea as he sat upon Ginger Mick in his Sunday best, swatting a lazy hand at the flies that were gaining energy as the day heated up, he wanted little more than to see how engineers could suspend all those tonnes of steel over such a wide space. He was fascinated by engines and engineering. A potentially skilled draughtsman, he could have made a career out of that, but a few years later, when his parents scraped up money for a drawing teacher, the man ran away with the cash before Lennie received a lesson.

When they did get machinery on the farm Lennie understood it better than he understood himself. Later, after his journey, he left Gippsland and took up a job as an engineer in an automobile factory in Melbourne.

It was hot the day Lennie set off, but the previous winter, the winter of 1931, had loomed cold and miserable for Lennie, the Captain and the rest of the Gwythers on their farm which snuggled in land below the road that ran out of town.

The family had known plenty of hard times since the first Gwythers cut a path through the virgin bush to the district in the 1870s. Over the years they had set about clearing the giant blue gums and thick forests, opening up the red volcanic soil of the rolling hills until the area began to resemble the old countries. When the railway came through the family farm earned its own siding, which meant the men could load their hessian sacks of potatoes straight onto the trains and not carry them along the 7 km of rutted track that led into Leongatha proper.

Lennie was the eldest son of Leo Tennyson Gwyther, war hero and farmer. His father was known, and insisted upon being known as the Captain. He was a strange fish, the locals said, an officious and aloof man, shaped by a terrible war and two generations of hard farming. The Captain served with the first battery of the field artillery at the Somme and Gallipoli. In November 1916 at Flers, France, his battery came under heavy fire and a shell hit the ammunition pit, which began to burn and threatened to explode. Gwyther ordered his men to evacuate, but one man was buried in a dugout and could not escape. Just the day before Gwyther, too, had been buried in a dugout by enemy fire which had killed the two officers with him. Despite the shelling and obvious danger, he could not leave the injured soldier and began digging. For fifteen agonising minutes he pawed at the French mud, shells falling around him, the burning munitions set to explode at any time. Eventually, with the help of another soldier, he freed the man and the trio escaped to safety.

The advent of the aeroplane meant artillery positions were extraordinarily vulnerable in World War I. The enemy planes would spot the positions and relay locations to their own guns. In July 1917, near Zillebeke Lake, Belgium, Gwyther’s outfit were again bombed while digging in, again the munition dump caught fire and again it was Gwyther who braved the flames and imminent explosion to put out the blaze, receiving severe burns to both hands in the process.

For his bravery he was called to Buckingham Palace and presented with the Military Cross and bar by the King of England.

The Captain came home proudly decorated but with the sounds of enemy bombardment ringing in his ears, his skin scarred and his lungs burned by mustard gas, his legs so badly ulcerated that one was eventually amputated — but not before causing him years of agony. Despite the injuries, he rode his horse and buggy about town straight-backed and dignified. When it rained the paddocks and roads around Leongatha became boggy and impassable. It reminded him of those times when he and his men showed their real mettle. After the war he married Clara Amelia Simon, the daughter of another pioneering Leongatha farm family. The Captain wore his uniform, his riding jodhpurs tucked into high polished boots, the medals of bravery pinned to his chest. He took his wife back to farm a part of the family property he dubbed Flers after that terrible place on the Somme where he first earned a Military Cross.

In 1932 the Captain was only 40 years old but already an old man who had seen the King in his English palace and a muddy hell in what had been the farmlands of Europe. He would only live another seventeen years.

Lennie was achingly proud of his father; after all, the Memorial Hall and Memorial Theatre at the top of town were built to honour men like him. He was probably too young in 1932 to understand the psychological damage the war inflicted on people like his father. In Australia, the war’s cost was not measured in the damage to cities and borders, but by the damage to the men who did not return and those that did. Many carried crippling physical and mental scars which took their toll on their families and the country for decades to come.

Up in Sydney, Norm McAlpine, another soldier’s son, did it tough. His father, too, had fought in the war. ‘He was released in 1918, or 1919 and then he went around the country quite a lot,’

Norm recalled. ‘I remember seeing him on the tram when he went away. He left me with about two shillings I think. He put two shillings in my hand when he got on the tram.’ Norm would sometimes see his father around town. ‘He was the kindest and most gentlemanly man, but he drank. Of course he used to turn up at all sorts of places… he never lifted a hand to me.’ Norm left school early to care for his sick mother, and the landlord of their Darlinghurst flat found him a job in the workshops for the Sydney Harbour Bridge unloading steel plates that came on ships from Newcastle and England.

Many returned soldiers had trouble settling back down to life. Others slowly rotted on the ill-fated soldier settlements, unworkable portions of land, divided from bigger farms and handed out to the ex-diggers to remove them from the cities where there was no work. Few of the men knew about farming and even if they did the land was often so barren nothing could be grown or grazed on it. They were encouraged to borrow to survive and then driven from the districts when they could not meet the payments.

The soldiers, despite policies that encouraged their employment ahead of other men, again found themselves marching in small armies from town to hostile town.

The Captain was among the lucky ones. He returned home to the farm, started his family and quietly dealt with his demons, but his health was not good. To make matters worse, in 1931 the Captain fell and broke his leg and was taken to hospital in Melbourne. His pain was compounded by the knowledge that the fields needed to be prepared for planting and if it wasn’t done there would be serious difficulties ahead.

With nobody else around to help, Lennie harnessed a four-horse team and set about ploughing 24 acres of the rich, dark soil to prepare it for sowing. It is back-breaking work for a grown man, let alone a pre-pubescent boy. Day after day he worked behind the horses, determined to fulfil his role as the man of the family. Somehow, he managed to harrow and smodge (smooth) the fields and the crops were eventually planted.

When the Captain returned from hospital he proposed a reward for the boy.

Lennie knew exactly what he would do. He had sat at the kitchen table in the farm, poring over pictures and descriptions of the Sydney Harbour Bridge for most of his life. With the combustion stove crackling in the dark kitchen he announced that he would like to ride his horse to the New South Wales capital that summer and arrive in time for the opening ceremony.

He would be alone on the road, but not in his quest. While they did not leave as early as Lennie, thousands had booked special trains from Adelaide and Melbourne to be on hand for the celebrations. The opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge was a bigger event in Australian history than the Sydney Olympics 68 years later and almost everything else that happened in between.

The Captain decided the boy could go and his mother swallowed her concerns as she set about manipulating the family’s thin budget to buy him a new suit for the ride.

And, on that summer morning in February 1932, the time had come for him to leave. It was almost 1000 km to Sydney and estimates said that it should take him 35-odd days to get there. The opening ceremony was scheduled for 19 March which meant there was no rush, but Lennie was keen to get going.

The boy was up early and put on his suit — a woollen jacket and short trousers — rolled his spare clothes inside an oilskin swag that sat across the front of the saddle and slung a sugar bag of rudimentary supplies over his shoulder. He had a special sou’wester-style hat for the ride with a brim that turned up at the front and hung low behind to protect his neck from the sun. After saddling up Ginger Mick he and the family rode into town early as the Shire President, Bob McIndoe Jr, had arranged to see him off from the showgrounds.

His three younger siblings gathered around their mother’s skirt, as unsure about the fuss as she was about letting her determined nine-year-old ride away. His mother worried as much about the journey as the destination; the roads and rural towns were crowded with hungry men, but the Captain was sure his eldest was up to it. It would make a man of him. Lennie would celebrate his tenth birthday on the road and would not be back until summer had passed and winter set in. The plan was for him to ride to Sydney and then to book a berth on a ship once he had finished with the bridge and the Easter show.

Lennie, at nine already an accomplished horseman, had grown up with Ginger Mick, a dark chestnut horse that stood 12.2 hands high who was the same age as him and was a present from his maternal grandfather. A horse is no indulgence for a country boy when he lives 7 km from school. When the work was done they competed at the Leongatha, Forster and Yarram shows in the schoolboy events and often won prizes.

Lennie loved his horse. He would tell a newspaper man: ‘He is quiet, and does not mind double dinkey in the least, has a few tricks, and is easy to catch and lovely to ride, game as they are made and can carry twelve stone without effort. A real keen stock pony, that can stick like a leech to a beast; you almost want some glue on the saddle to stick to him when he screws and twists after an animal.’

Ginger Mick had been spelled for six weeks before setting out and the toes of his shoes were inlaid with a piece of motor spring steel which would be good for at least six weeks.

While most of the journey would be on dirt, some roads near the cities were sealed and hard on the horse’s feet.

With a small crowd looking on, Councillor McIndoe made a short speech to Lennie, presented him with a letter of introduction to the Lord Mayor of Sydney and it was time to go.

The nine-year-old said goodbye to his family and set off. A photograph shows the boy and Ginger Mick on the main street, Lennie in short trousers, a woollen coat and the odd hat. Nobody else is in frame. The family have dug deep to clothe him properly for the trip and he looks suitably respectable. Ginger Mick, ears pricked, is turning from the camera, apparently eager to get on the road.

‘Leaving the South Gippsland capital with the benediction of his parents ringing in his ears, the lad turned in the saddle, and looking back on Leongatha, commenced the climb to Mirboo,’ reported the Journal on the following Monday.

Lennie and Ginger Mick climbed north-east from Leongatha, the sounds of the show fading in the background as they rode away. It was a steep, winding road and while there was at least 1000 km ahead of them, Lennie knew that it all had to be done with patience.

Ginger Mick needed to be rested often if they were both to make it. After a steady day they stopped and camped at Mirboo North, about 25 km from home and barely twenty minutes in a modern car, but a fair day’s ride for a boy on a horse. The next morning they were on their way early, continuing along the winding road, through Boolara and Yinnar, then dropping down into the dairy farms of the Latrobe Valley. They rested at Morwell, before pushing on and it was almost nightfall by the time they reached the outskirts of Traralgon, but they were still earlier than expected.

The Gwythers’ family friend Sam Phillips, a local horse trainer and Vacuum Oil Company man, was supposed to greet them on the road, but Lennie arrived in town early and knocked on the door of George Sparke, who steered him in the right direction. Traralgon was the biggest town in the area, but still small enough for everybody to know everybody else. After Ginger Mick was watered and bedded down for the night, Lennie was fed by the Phillipses. Later, an exhausted little boy climbed into bed for the night. Meeting the Phillipses was fortuitous; Vacuum Oil had representatives in almost every major centre from Traralgon to Sydney. The company had been importing bulk oil shipments for almost a decade to cope with the increasing demands of the motor vehicle, and later would be better known as Mobil. Lennie might have been on a horse, but the Vacuum Oil men were sent a message to be on the lookout for the little fellow and to extend him every courtesy.

Even in 1932, the boy and his horse represented an era that was fast passing. Perhaps that was why the quiet soldier’s son received so much attention. Lennie and his horse appeared to have materialised from the bush folklore of Banjo Paterson and the devil-may-care characters of C. J. Dennis. In fact, Ginger Mick’s name was taken from one of Dennis’s larrikin inventions — Mick was a knockabout Melbourne type who fought and died at Gallipoli.

The Traralgon press was certainly impressed by the young visitor and the following Monday the Journal published an article under the banner: A STURDY LEONGATHA BOY WILL RIDE TO SYDNEY ON PONY TO HARBOUR BRIDGE OPENING. A smaller heading noted: Nine Years Old — But Can Plow as Well. The journalist was clearly more impressed with the boy’s efforts than those on his home town paper. The article began: ‘A little lad, on a stocky pony, parked in front of “the Journal” early on Friday morning . . .’ It detailed Lennie’s journey so far, the reasons he was on the way and finished with an encouraging two-word flourish: ‘Atta boy!’

Friday was only Lennie’s third day on the road, but it could easily have been his last. He set off from Traralgon early, but by mid-morning a terrible hot northerly was blowing gusts of smothering wind into the valley, filling the air with dust and then, more worryingly, smoke. In no time the pair were lost in a thick, choking cloud, blown down from the hills to the north as a fire raced through the heavily timbered hills. At midday it was pitch-black, the sun completely eclipsed by the smoke. There was another large grass fire raging ahead, around the Bairnsdale area. Lennie and an agitated Ginger Mick rode blind, not sure if the fire front was about to leap out and consume them, and aware only of a deep burning red on the horizon to the north, east and west. It was a terrifying day for everybody in the area, but particularly for the boy alone on the road.

The blaze to the north burnt through the milling towns of Erica, Gilderoy, Warragul and Noojee. O’Shea’s sawmill, 6 km from Knotts Siding, was right in the path of a fierce blaze.

Local schoolteacher, Mr Vague, rode out to warn the workers. The mill was surrounded by firebreaks and had a modern sprinkler system to protect the buildings and men from just such an incident, but a falling tree cut the water supply and the workers had to run for their lives. Some made it to a nearby river, remaining partially submerged until the front had passed, but nine were killed, including the schoolteacher Mr Vague.

After a 20km ride through the black smoke, Lennie and Ginger Mick were relieved to arrive at the home of relatives at Kilmany, near Rosedale. Lennie saw to his horse and then washed the soot from his face and eyes. He was lucky to be alive, homesick and reconsidering the whole adventure as he fell to sleep. Saturday, however, arrived clear and fresh. The north wind had died and Lennie needed his oilskin before the day was over as rains brought relief from the fires and the heat. That night he veered off the road to stay with Mr and Mrs Rash at Munro and by Sunday he had arrived at the large rural centre of Bairnsdale, where he stayed the night with his mother’s best friend from her school days, Mrs Furnier. The family operated the Main Hotel, where he was given a room for the night.

On the front page of the Bairnsdale Advertiser readers were informed that ‘Lennie Gwyther, to give him his full title, has more than the usual quota of self assurance for a lad of his years, and has absolutely no fears for his future . . . the lad weighs five stone and the saddle is only 10lb more so Ginger Mick’s load is not a heavy one . . . the youngster proposes to complete the journey to Lang’s capital alone.’

Back in Leongatha, Tuesday passed but there were no reports in the Great Southern Star, which seemed to share some of the town’s cynicism about his adventure, but other papers, including Traralgon’s Journal picked up the story and stuck with it. Lennie was suffering a prophet’s lack of recognition in his hometown, but couldn’t have cared less. He and Ginger Mick had fallen into an easy rhythm and were enjoying the journey along the less populated eastern extremity of the state. An independent boy, Lennie didn’t want for company, falling in with people on the road and stopping regularly to water the horse and rest at convenient homesteads.

Still skirting the ranges to the north, the pair continued along the long straight plains heading due east towards Sale and then made it to Cann River, 400 km from home and almost halfway to Sydney. From there the Bombala road veered directly and steeply north. Captain Gwyther had planned to drive the family jinker to meet his boy at the town in the far east of the state, but accepted a lift in a neighbour’s Model A Ford and the pair were reunited in Cann River. Along the way the Captain dropped into Traralgon’s Journal to inform it of the ‘courageous little lad’s’ progress: ‘It is quite possible,’ said the Captain, ‘that if I were to go right on to Sydney with my son, it would take much of the glamour off his enterprise, and it is therefore more than likely that I shall turn back after I see him safely through Bombala.’

‘The game lad is in excellent fettle, the captain told us, and the pony looks as though he had not travelled more than a few miles,’ the paper in turn told its readers.

The Captain escorted the boy from Cann River along the first sections of the Monaro Road, a trail that wound up into the lower reaches of the South Coast Range before joining the Great Dividing Range. While not an easy route, his father hoped it would at least avoid the extremes of the coastal climate. Father and son made it to Bombala on Friday 19 February, almost three weeks after leaving home. The pair were greeted by the local mayor, Alderman Charles Warne, and Lennie was then taken to the schoolhouse where the children were given rides around the oval on the patient pony before Lennie found lodgings at the Globe Hotel.

Captain Gwyther took his 5-stone (32kg) son to the local GP to see how he was holding up to the rigours of the relentless dusty road and occasional civic receptions. The doctor proclaimed Lennie ‘as sound as a bell, and in buoyant spirits’.

By now his journey was starting to gain attention in Sydney, where everybody was eagerly preparing for the following month’s bridge celebrations. The Sydney Morning Herald reported on his ride on 20 February 1932.

Above the item were details about a police case against Eric Campbell, leader of a right-wing militia group based in Sydney called the New Guard. Campbell was facing charges of using insulting language toward the Premier of the state. Lennie and one of Campbell’s horsemen would cross paths in the following weeks and share more newspaper space.

On his return journey from Bombala the Captain dropped in to the Journal office to update them on the Game Little Chap — as the paper had dubbed its Leongatha Boy. Lennie and Ginger Mick were travelling without incident but Lennie’s father almost came undone on the journey home, running the Model A off the road and losing a mudguard in the process.

Lennie and Ginger Mick continued along the Monaro Highway, spending Sunday night at Bobingah Station and stopping for lunch at Rock Flat. They were greeted at Nimmitabel by a party of men and boys who rode along the road and escorted them into Cooma on Monday 22 February, and Lennie was invited to stay with the Rolfes, who owned the Prince of Wales Hotel.

While it might have been hard on the road, Lennie was spending his nights like a little prince, fêted by civic leaders, fed in hotel dining rooms and sleeping in hotel suites. It was a far cry from the anonymous, hard life on the little farm back in Leongatha and must have seemed like a fairytale to the little boy. No school, no curfews, no chores and nothing but a ribbon of dusty road ahead.

They respected a horseman up that way and ‘the lad was given a great welcome when he arrived, particularly by the many local lads who envied him his adventure, and admired his staunch little pony, very aptly named “Ginger Mick”’, the Cooma Express reported. Lennie was taken to the hotel before heading into Centennial Park for a ‘romp’ with some of the locals. Later there was a community singing around the piano at the Rolfes’. The boy had a bonza time before setting out again the next morning escorted by Tom Stroud and the Body brothers, John and Edmund. ‘It was characteristic that when Mrs Rolfe asked him what he would like in the lunch she was making up for him to take with him he asked her not to worry about him but to put in an apple for his pony.’ Then, according to the Cooma Express, it was on to the Quarmbys’ at Bredbo and the Kellys’ at The Creek, Michelago.

By Friday 26 February Lennie was approaching Canberra and on the downhill run toward Sydney. While at Bombala he had received a telegram from the headmaster of the Canberra Grammar School offering him accommodation on the campus, but before bedding down, Lennie had some official duties to attend to: Charles James Gwyther, 9, rode his chestnut pony up to the steps of Parliament House this afternoon and paid a courtesy call on the deputy leader of the United Country party (Mr Paterson) who is the member for Gippsland, in which his parents have a farm at Leongatha ... Mr Paterson was extremely proud of his guest, and introduced him to nearly every member of Parliament. It was not surprising that the boy was overwhelmed and bewildered. Then Charles was entertained at afternoon tea in the refreshment rooms reserved for ‘members only’.

He has a diary recording the towns at which he has spent the night and the names of his hosts. Only once, he said, had he been refused shelter. That was at a town near Sale, Victoria. There, one resident refused to take him in. The occupant of another house was absent, but he received a warm welcome at the next house at which he called.

Charles Gwyther said that he intended to write a book of his adventure on his return home … Canberra is a proper place and the paper used the boy’s real name, although he was known to all as Lennie. Canberra also found him ‘overwhelmed and bewildered’, a theme the Sydney newspapers would return to and a fair indication that the taciturn young man was less than comfortable with all the attention, especially in the larger cities. His private journey had become confrontingly public. Lennie obviously did not lack confidence in his ability to ride the distance but the real fears of the skinny farm boy were to do with town halls and sitting rooms, not open roads and country towns. His reported intention to return by steamer was later abandoned as the nine-year-old had fallen in love with the rhythms and sights of his journey and was beginning to form a plan to return home via Melbourne.

The visit to Canberra made news in Sydney and the towns he had been to previously and even sparked the Great Southern Star into the first mention of the local lad since he had left town a month before. On 1 March it reported in the Personal Column:

Captain Leo T. Gwyther received a telegram from the Hon T. Paterson, M.H.R. on Friday last stating that his son Lennie arrived safely that day at Canberra, looking well, and the pony in good condition. He was to stay two days at the Grammar School and then leave for Sydney. Lennie Gwyther, aged 9, left the Leongatha show ground on February 3rd, on his pony, for Sydney, and should shortly arrive at his destination.

With Canberra behind them, the pair now had Sydney in their sights. On the way to Queanbeyan, Lennie was presented with a boomerang at Station Hill by a Mr Jolly — another souvenir for the sugar bag that was later said to also include a cricket bat autographed by cricketing legend Don Bradman.

In Queanbeyan he was again welcomed by civic dignitaries, including the deputy mayor and a councillor, then taken home by Sergeant Ruffles and fed dinner. The Queanbeyan Age was impressed. ‘It is questionable whether there is another lad of Lennie’s age, who can boast of attempting such a big journey all alone. Everybody who meets young Gwyther and ‘Ginger Mick’ will wish the pair the best of luck. A real Aussie, with that inborn pluck, prepared to tackle anything.’

On Saturday 5 March Lennie trotted into Moss Vale on Sydney’s outskirts. By now the Great Southern Star was showing a little more interest in the story, reporting:

A message from Sydney states that Lennie Gwyther, who set off for Sydney from the recent Leongatha show, for the purpose of viewing the opening of the harbour bridge, rode on to the Moss Vale show ground unannounced on Saturday last, and entered in the class for boy riders under the age of 10 years. He won second prize and was awarded a special ribbon from the society. He afterwards continued on his journey to the capital. Lennie is the son of Capt. and Mrs Leo Gwyther and his friends will be pleased to hear of his successful progress.

Clearly, Ginger Mick was still in fine fettle. Lennie reached the outskirts of Sydney, stopping to rest at Liverpool that Saturday where accommodation had been arranged by the Royal Agricultural Society. He woke early the next morning, keen to get into town and see the Sydney Harbour Bridge, but as he groomed Ginger Mick in preparation he was set upon by a film crew from ‘the talkies’ keen to record an interview. Two escorts arrived from the Royal Agricultural Society. Finishing the interview, Lennie could wait no longer. ‘Now let me see your bridge — quick as you can,’ he told his guides.

Finally, on 8 March 1932, 33 days after leaving Leongatha, Lennie and Ginger Mick rode through suburb after endless suburb, toward the city.

As they approached Martin Place, where one last civic reception stood between him and the bridge, Lennie’s heart must have fallen slightly, for a large, pressing crowd had spilled into the streets despite the best efforts of two dozen policemen.

The child from Leongatha was received like a returned explorer from an earlier century but was sick of ceremonies. The pair picked their way through the surging city crowd, then Lennie alighted from Ginger Mick and finally set his country boots down on the paved streets of Sydney.

‘Oh what a bonza town!’ he exclaimed to the waiting dignitaries, his eyes darting from one grand building to the next. He had never seen so many people in one place and you can imagine the sight of the city buildings to a boy who had never seen anything bigger than a gum tree or a grain silo. It was all a little overwhelming.

The event was recorded by the Sydney Morning Herald and the next day it ran a report with a photograph of Lennie and Ginger Mick. Sydney, it seems, had fallen for the pair, although another report told how souvenir hunters pulled hairs out of the pony’s tail, no doubt confirming to Victorians some of their mistrust about Mr Lang’s capital and its inhabitants. Most Sydneysiders, though, seemed genuinely moved by the anachronistic sight of the little farm boy who was drawn to their city and bridge. Three days after Lennie arrived in Martin Place another article appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald, apparently written by the young horseman, although it was more likely concocted by a reporter after discussions with the monosyllabic traveller. Still, it’s an insight into Lennie’s world.

… I know that I have bitten off rather a big chew, as sailors say, but education is what I want, and it’s one of the main objects of my trip. Amongst the many things I have is a letter from the president of our local shire to the Lord Mayor of Sydney, as I am desirous of seeing the opening ceremony of the bridge, and would be glad to see also the Sydney Show and the yearling sales of thoroughbreds … Do not think that I want to be adventurous. Not so. I am contented, but I did want to see the biggest bridge in Australia and the greatest ocean-going liners that call at Sydney’s beautiful harbour.

“I visited Melbourne when the Hood was here, and was on her at Port Melbourne. One sailor wanted to put me down a big gun muzzle, but I was quite off being cannon fodder; not that I would mind, perhaps, when I am older, since for over five generations there have been soldiers in the family. A photograph of the painting of the Scotch Greys (the 2nd (Royal North British) Dragoons, so called because they are mounted on grey horses) is my very special fancy, for I love horses and a gallop. My father, of whom I am very proud, is a captain, and won the Military Cross and a bar, and was twice decorated at Buckingham Palace by the King …

Lennie was a hero in Sydney, one letter writer seeing in him values that made the humble colony the equal of any nation.

Sir, — Just such an example as provided by a child of nine summers, Lennie Gwyther, was, and is, needed to raise the spirit of our people and to fire our youth and others to do things, not to talk only. The sturdy pioneer spirit is not dead, the spirit that explored and settled this country and is now operating in Central Australia.

The patriotic writer, using the nom de plume ‘Gum Tips’, invoked the names of the conservative Prime Minister and Colonel Lindburgh (‘who I feel safe in saying could easily be beaten by at least a score of Australians, and possibly equalled by 100’) and ended with a swipe at those on the dole.

A reporter from Melbourne’s Age was also moved by the reception at Martin Place.

The had been royalty he could not have got a better reception. Thousands awaited his arrival in Martin Place, the scene of great receptions. They were not all Victorians. There were some who showed themselves proud of the State that could produce such a youthful adventurer. But the majority of those who shouted a welcome to the boy did so because he was an Australian and to be an Australian in getting a first and foremost place in our estimate of things. Perhaps the welcome given to the boy was not unexpected for children and youth seem to be playing an important part in bringing about a better understanding between the various States.

He might be a Victorian and an Australian but he was also a Leongatha boy and the next edition of the Great Southern Star carried the item from the Age.

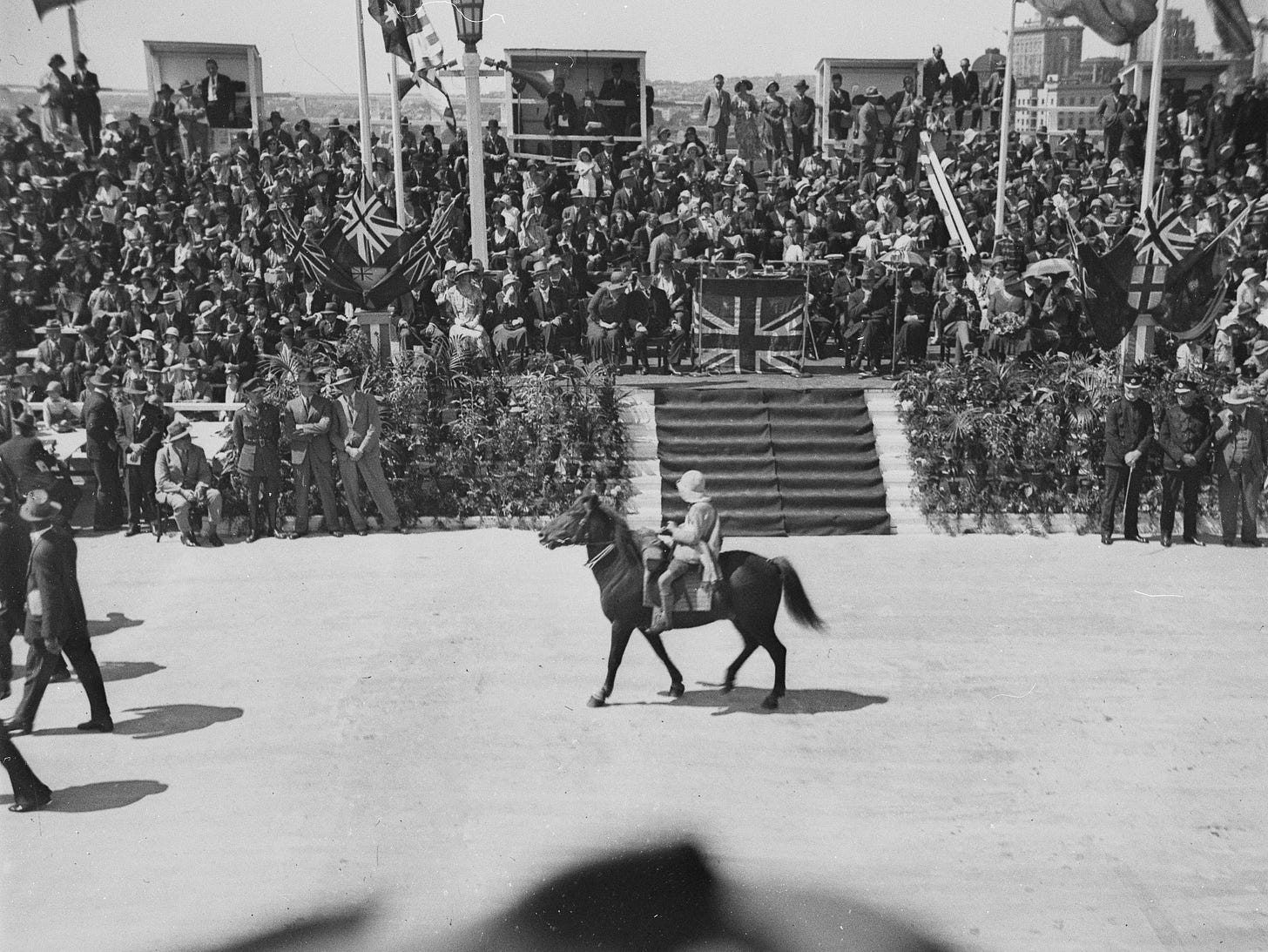

Lennie was in for a further surprise in Sydney. He was invited to join the official celebrations for the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge on 19 March, the biggest event ever seen in the city. Lennie would ride Ginger Mick ahead of a group of Aboriginals gathered from near Botany Bay who would be daubed in white paint.

Sometime the following week the fares for crossing the bridge were published in the Sydney papers. While Lennie could cross the structure for free on the opening day, any subsequent trips would set him back threepence, although a herd of horses or cattle was cheaper at twopence and sheep or pigs could cross for one penny.

The Australian horseman was not dead just yet. The opening ceremony of the Sydney Harbour Bridge gave one in particular the chance to almost steal the show — but it wasn’t Lennie Gwyther.

Come for the cricket, stay for the Et Al, thanks

Peter, thank you for reproducing this for us. Much appreciated - living 30 minutes out of Leongatha on the coast at Cape Paterson. A great read!