A night on the tiles and a Catholic saint's severed arm

Things get weird in Lisbon

If you were listening to The Podcast Formerly Known as Cricket Et Cetera during the 2023 Ashes, you may recall our day trip to the magnificent Crossness Pumping Station, opened in 1865 as part of Joseph Bazalgette’s London sewerage system and still critical to the disposal of that city’s shit and piss over 150 years later.

What a thrill it was to board a miniature train named after the engineer – and to stand on the ground above the pipes channelling all that effluent.

Made ya think …

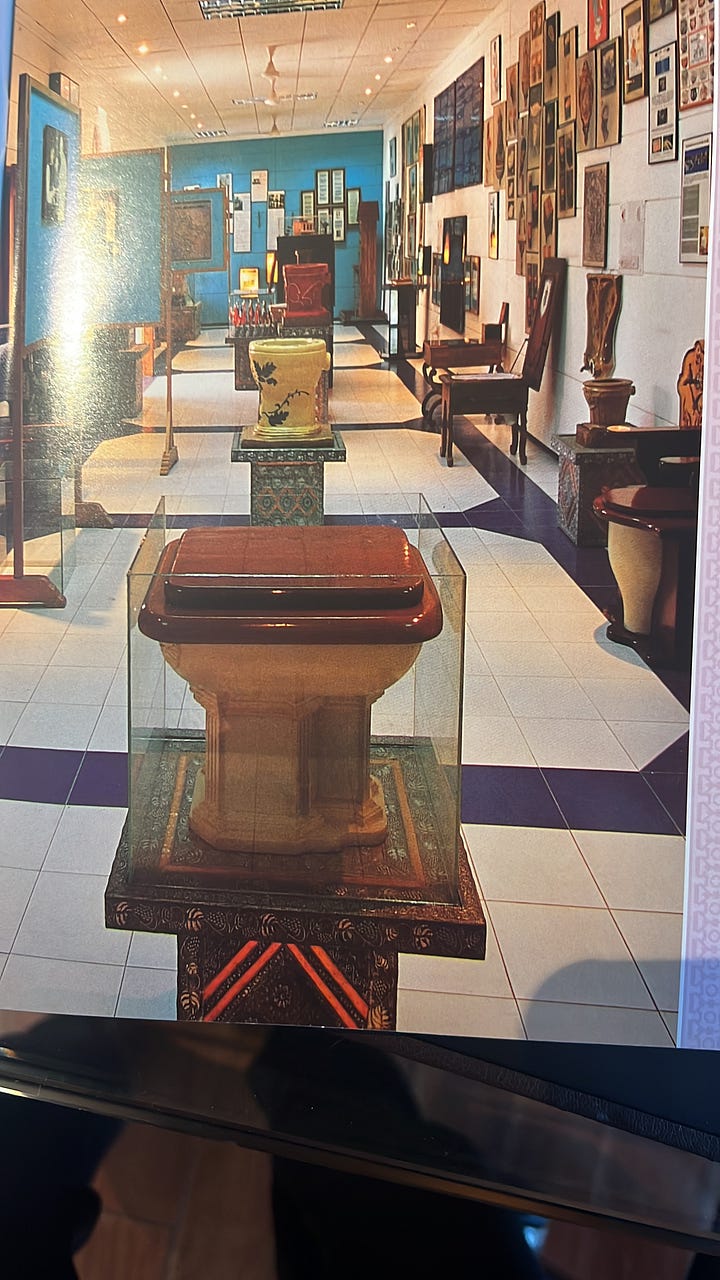

Had you tuned in early that year, when we were in Delhi for the Border-Gavaskar Trophy, you’d have heard our raputurous account of a similar pilgrimage to Sulabh’s International Museum of Toilets.

There was, then, a sense of continuity on making my way to Lisbon’s Museu Nacional do Azulejo (National Tile Museum) with Sue as we circle England in a holding pattern, waiting for Gideon to arrive and the World Test Championship final to begin.

Tiles in Lisbon, dunnies in Delhi, crap in Crossness … I’m sure you can see the connection.

Ostensibly and successfully devoted to Lisbon and Portugal’s traditional ceramic azulejo (tile), the museum, like Crossness, seamlessly blends inspirational form and fascinating function. Housed within the 15th-century Madre de Deus Convent, the museum also allows itself a wide diversion into the weird and wonderful world of Portuguese Catholicism.

Hang with me here, this was some mindblowing stuff and a place that allowed me to complete a curious circle that involves a saint buried so often he could qualify for frequent flier points and one who I first came across in Goa on my first trip to India some 30 years previous.

More of him later.

Underwhelming though it may sound, the Museu Nacional do Azulejo is was one of those museums that leave a curiously profound impression. Indeed, it’s rated as one of the must-visit attractions in this great city. I’m putting it up there with New York’s 9/11 Memorial & Museum and Ireland’s Titanic Belfast (“built by the Irish, sunk by the British”).

That said, I’ve never visited the Murtoa Stick Shed, but having been regaled of its magnificence by Gideon and his mum, I’m sure I’d include it if I had. (Just quietly, Gids – who can knock up a 5000-word deep dive into cricket’s geopolitics between breakfast and elevenses – sweated for months, carefully crafting the unforgettable Et Al post Why You Must See the Stick Shed, which we published in February).

Nor, sadly, have I visited the British Lawnmower Museum, which boasts (for those who can’t be fagged clicking the link it claims to be:

one of the Worlds leading authorities on vintage lawnmowers … now specialists in antique garden machinery, supplying parts, archive conservation of manuscript materials and valuing machines from all over the world. See 'Lawnmowers of the Rich and Famous' including Prince Charles and Princess Diana, Brian May, Nicholas Parsons, Eric Morecambe, Hilda Ogden, Alan Titchmarsh and many more.

Humanity needs more esoteric shrines. Should his cricket writing gig ever go bust, I could see Gideon coralling Janeen into his great passion project: The Timboon Mailbox Museum. A whole wing devoted, no doubt, to the repurposed microwave mailbox.

Being the husband of a painter and ceramicist, there was no way I was not going to the tile museum. It was the first thing on our Lisbon list, and thus we headed out through a fog of jetlag on our first morning in this wonderful city.

Lisbon loves a good tile. The kitchen in our apartment on Rua do Vigario in the Alfama district boasts as good a tile floor as I’d ever seen.

I am not going to go on and on about tiles here, but a few things need to be recorded.

For starters, I have an inkling that old mate Henry Lawson was inspired to write The Loaded Dog after seeing this emblem of the Dominican Order in Lisbon:

Sue was in her element and did her best to avoid my annoying commentary, but every time she gave me the slip, I managed to find her and begin afresh.

The Museu Azulejo walks you through the history of the tiles, their use in private and public life, much of which is centred around their incorporation by the Catholic church through the ages. Progressing chronologically, the tile section of the museum concludes with a brilliant display of the object as art in modern life. Never heard of Querubim Lapa (1915-2016)? Do yourselves a favour and catch up with an artist billed as “one of the foremost creators of contemporary Portuguese tiles”.

Recreated in the museum is the kitchen of a Lisbon apartment he was commissioned to tile in the late 1980s. The endless whimsy in the detail would certainly make this a popular place in any party (apologies to Jona Lewie, author of the 1978 banger You’ll Always Find Me in the Kitchen at Parties).

An explanation on the wall tells visitors this is a riff on the kitchen as a place where “one eats and is eaten” (Jose Luis Porfirio).

As noted earlier, the tiles are housed in a 16th-century mannerist cloister, formerly home of the Convent of Madre Deus (Mother of God). Now, this Bendigo boy may have strayed some distance from the path and from that town, but the burden of Catholicism, like Jesus’ cross, must always be borne.

So, back to India and back to my roots.

In one corner of the cloister, as one approaches the chapel (Capela de las Albertas), where nuns from the Order of the Discalced Carmelites once worshipped, there is this wonderful image of St Francis Xavier, the globe-trotting Portuguese missionary and co-founder of the Society of Jesus.

(There is not world enough or time for me to include the story of my family connection to the Carmelites, but let it be known that two of my dad’s sisters joined the order – one, Mother Mary Lalor, founded the Little Sisters of Our Lady of Mt Carmel, but you may look up her biography should you wish. Please disregard unfounded reports that claim my grandfather sired 16 children – it was only 12.)

Anyway, St Francis set a trend that was later followed by every hippy who ever grew their hair – including me – when he dropped into Goa back in about 1542, but this was a man who travelled widely and who corresponded profusely.

Here is a picture of him rendered in azulejos at the museum.

St Francis’ extensive missionary work was briefly curtailed when he died on the Chinese island of Shangchuan in late 1852, but this is when his story gets really interesting. Someone buried him in a lime-filled coffin on a hill by the beach before he was dug up some months later by Portuguese merchants tasked with returning his body to India.

There are varying accounts of what happened when he was disinterred, but they tend to agree that his body was so well preserved that when the thigh was cut to make an examination, it bled. A miracle was at hand and one account says the men of the crew who had doubted him and his role in God’s great plan “crowded round, weeping, and begging pardon for their neglect and coldness”.

St Francis’s sprightly corpse then had a stop over in what was then Portugese Malacca, where it was paraded through the streets, instantly ending a rather nasty case of the plague that had beset the area and was then taken to Our Lady of the Hill, a Jesuit church, in Portuguese Malacca on 22 March 1553.

And he was buried again.

Francis was not, however, allowed to rest in peace and was dug up again by a group of attending Jesuits who, again, found that not only had it not decayed, but that it smelled “exquisite”.

(I’m basing some of this account from the pages of the 600-page The Life and Letters of St Francis Xavier Vol II written by the Rev Henry J Coleridge (great nephew of the poet Samuel) of the Society of Jesus and published in 1872. The work is reproduced online by the Rare Book Society of India. It’s a hell of a read if you have the interest and time.)

St Francis’s corpse was eventually moved to Goa where it bounced around for a while, smelling sweet and triggering miracles, before finding a permanent resting place at the Bom Jesus Goa.

But wait, there’s more!

There are some claims – difficult to confirm – that during all of this moving around that the boss Jesuit ordered the arm Francis used to bless congregations be cut from the corpse and sent home.

I know, I know, this is sounding a little like that Mexican film “The Three Burials of Melquiaddes Estrada”, directed by and starring Tommy Lee Jones. If you haven’t seen it, you must. It’s, ahhhh, different, but not that far fetched after you’ve had a look at what happened to Francis.

Almost 400 years later, I stumbled across the final St Francis, lying in a glass coffin in the Basilica of Bom Jesus, after making my way to Goa on what was the first of my many trips to India.

I’d just lost my job as producer/writer of Take 40 Australia and was at a loose end.

The saint’s story has stayed with me ever since.

The Basilica of Bom Jesus was, from memory, rather plain, but the chapels of Saint Anthony and Queen Leonor in the National Tile Museum is one of the more extraordinary I’ve encountered.

While modest in size, it contains a multitude of sacred distractions.

All the pieces of my life and the saint’s appeared to have come together when I spied this relic in a back part of the chapel:

Surely this was the saint’s severed arm? What else could it be?

My dear departed friend and “attorney”, Ken Oldis, a Melbourne QC who had worked tirelessly to identify and authenticate Ned Kelly’s armour, and I felt a moment’s connection with the mate I miss so much. (Ken had joined me for a while on that first trip to India.)

Alas, I was wrong, as a kindly attendant informed me that this wasn’t St Francis’s at all, but any disappointment suffered was soon assuaged by the distracting collection of saintly relics gathered in the chapel’s antechamber.

Nobody, but nobody, does gore like the Catholics and here were some delightful examples found in the cloister’s chapel.

I was taken by this charming assemblage of her skull and assorted bones.

And then there was the patron saint of breast cancer, St Agatha, an Italian devotee who had her breasts cut off during various tortures but who remained true to her faith through it all. I’ll let you work out what’s going on here, but I suspect that is a sample of ossified bone inside the image.

Substack is telling me I’ve gone too far with this post, so I will spare you any more from this collection.

Forgive them, they know not what they do.

PS: I’m off to Fatima. This journey is taking me to some strange places, but God willing, Gideon and I will be in place at the cricket soon.

A POSTSCRIPT FROM THE RIVER DUORO

I was something of a Doubting Thomas about the tale of St Francis’s amputation(s), but I came across Martin Page’s fantastic, The First Global Village: How Portugal Changed the World, just now and found this passage about the body of the globe-trotting Jesuit:

“His body, apparently embalmed by Chinese techniques unknown to Europeans, who attributed its preservation to a divine miracle, was eventually taken to Goa to be publicly exhibited in St Paul’s Cathedral. His physical remains did not lie in peace. Within two years, as an act of piety, Donna Isabel de Caron bit off one of his toes. In 1615, at the request of the then Vicar General of the Society of Jeseus, Sao Francisco’s right arm was severed below the elbow and shipped to Rome. It’s skeleton can still be seen there today in a glass case, in the Jesuit Church of Gesu. The upper part of his arm and his shoulder blade was cut off in 1619, and was sent to Nagasaki in Japan. As recently as 1859, during a special exhibition a portion of his toe fell off, which the governor of Goa sent to descendants of his family.”

Frankie had spent time in Japan debating theology with the Buddhist monks and made quite an impression. Of the many influences which remain, one is the Japanese word for thank you “orrigato” which derives from the Portuguese word “obrigado”.

On that note: obrigado and good night.

Wonderful! The preserved head of St Catherine in Siena is one of my favourites. Beautiful images too Pete.

Very “et al” today! When you mentioned the National Tile Museum, my mind forced me to read it in the style of Frank Walker doing his “National Tiles” commercial…