The Father Who Didn't

GH marks the day

At the Melbourne Writers’ Festival earlier this year, I was part of an event entitled Better Off Said, furnishing ‘eulogies for the living and the dead.’ I composed something for someone who is a bit of both - my father, still alive, but whom I have not seen in a quarter of a century, and will not again. I know it’s not exactly on message with Fathers’ Day, but those of us with nothing much to celebrate often feel conflicted around this date, so here it is, for what it’s worth.

In 2017, I contributed to a book entitled Father Figures: a score of writers writing, as the subtitle explained, ‘In Praise and Defence of Dads’. I furnished a short piece about my experience of being a father to a daughter, then aged seven. When the book arrived, I opened it to his introduction, in which editor Paul Connolly described the versatility that fatherhood calls forth:

A father, so it’s been said, must be a provider and a fixer, capable of putting a roof over his family’s head and then repairing it when it springs a leak. A father must be wise enough to guide his spawn through the dangers and risks of childhood, and stoic enough to deal with the fallout when it goes pear-shaped. A father should be tender enough to hold on to a newborn, and strong enough to undo the lug nuts on a flat tyre….

And so on, at affirming length – you get the idea. Whereupon I placed the book on a shelf at head height where, in the intervening years, I have occasionally sighted it, considered giving it another go, but haven’t. Because you, our father, did none of these things; you, our father, left us when I was six and my brother Jaz was two, and I have scarcely seen you since. I’m sure the other fathers described in the collection were variously noble, capable, steadfast and loving. But writing must call forth emotion in a reader, and I had none to offer save an undirected irritation. For in my life, you’ve been more hole than shape, an enigma barely worth clarifying, a hate figure for which it’s hardly been worth working up an enmity.

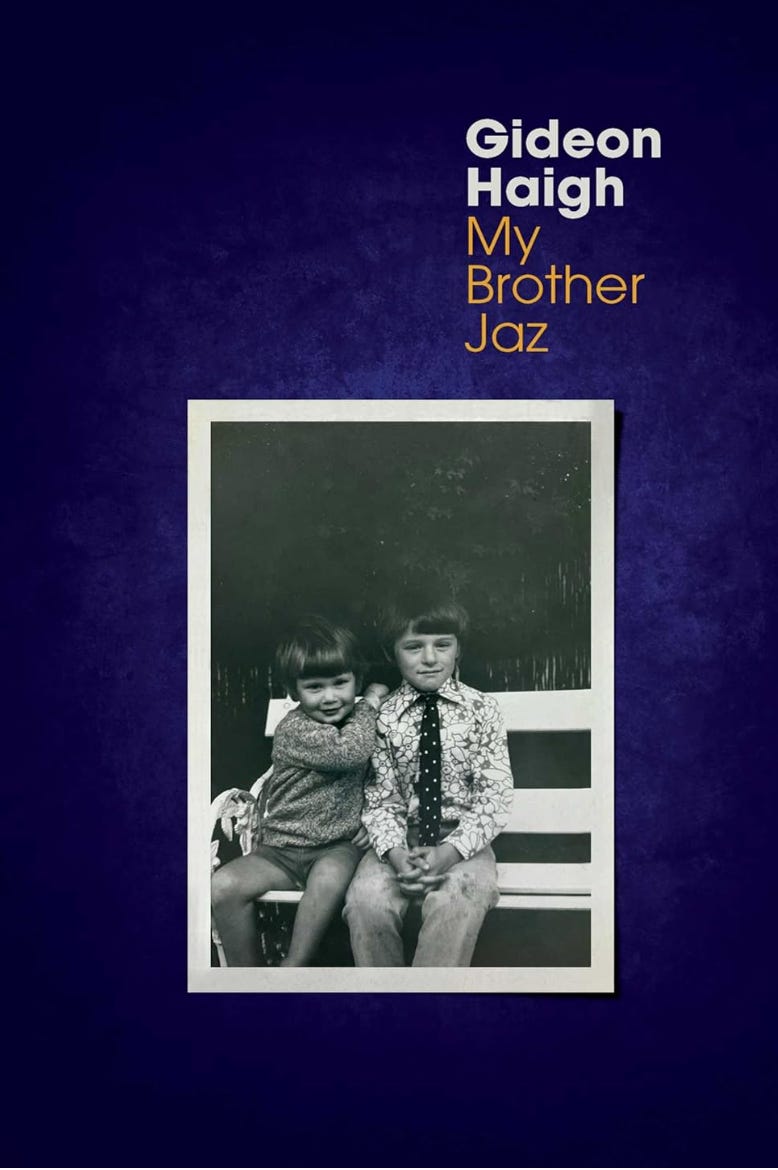

Many years have passed since we exchanged so much as an email, and I know only the scantest details of your life. Just recently, however, I learned that you were unwell, in care, with a degenerative condition akin to Parkinson’s. I learned its exact name, but immediately forgot it. I saw a photograph of you, but it elicited no recognition. I gleaned that the prognosis is unfavourable, that before too long I will have no father at all, rather than merely no father effectively. I’m also conscious I won’t be able to mourn you, in terms other than what you weren’t to me, which would in any case feel self-indulgent. What I’ll feel instead, I suspect, will be a modest intensification of a life’s uncaring. I won’t be at your funeral; I certainly won’t be called on for a eulogy. So this will be my only chance. Recently I wrote a short book about your other son, My Brother Jaz, who lost his life in 1987. And while rifling my memory, I realised you were in there, and had even exerted an unintended influence on my life.

You were born in England, where you married my Australian mother, and the three of us emigrated. I feel a little self-conscious about using the word ‘us’ here. I retrieved our assisted migration file a few years ago out of curiosity, and found it poignant. There is a photograph of me as a baby with my mother; there is a photograph of you. It was as though the universe intuited that our paths would diverge before we did.

There are other photographs in our family album too in which we look joint but several. Perhaps I am imagining it, but you don’t look comfortable as a father. You’re conscious of the camera. You’re performing your new role. We all do, to some extent. We share a cultural understanding that the arrival of a newborn occasions celebration; we feel in our confused elation an expectation to meet. But you’re young, aren’t you? You’re only twenty-three. You’ve come to the other side of the world. Are you already wondering how to slip these chafing bonds of responsibility? Not three years after our arrival, you’ll find yourself a father a second time. There are, I notice, scarcely any photographs of you with Jaz. I do know that by now you’re eyeing the exits. We’ve moved from Newcastle to Geelong, ostensibly for you to take a new job; in reality, I later learn, that you might continue an affair that you have begun. Two years later, on a business trip to the US, you’ll meet a third woman, who’ll become your second wife. Not yet thirty, you’ve already left two sons and two countries behind.

There’s a photograph of you at my sixth birthday. It will be the last one you attend. Then there are two other photographs which my mother has captioned: ‘The pictures Peter took with him to America.’ Baby-faced Jaz sits on a swing; I wear a crisp collared shirt and tightly-knotted tie, which I remember for my boyish pride in learning to tie. You know what I’m trying to do, don’t you? I’m trying to look like you; I’m trying to be like you; I’m doing what boys do, which is orient themselves in the masculine world by emulating the senior male of a household. And I’ll never do it again. Because you’ll return to Geelong, and tell my mother the marriage is over.

I’ll see you walking down the driveway that day. I’ll ask what you’re doing. You’ll say that you’re going away for a while. That’s all. But you’ll be right. Since then we’ve met precisely four times, in the main unmemorably. You’re not, so far as I can tell, a memorable man. I’ve strained at times to remember a game we played together, a toy you bought me, a favourite song, a favoured expression – but to no avail. Yet I look at that photograph of me, tie precociously tied, and know that, in that instant, I looked up to you.

Then I stopped. Because I conscientiously normalised the scenario of having a single parent – my mother, who did it all and more, striving every day, overcoming every obstacle, never openly blaming anyone, or exhibiting an atom of self-pity. I grew up fast, because it seemed to fall to me to assume your role, as a kind of proxy husband - it became part of my self-image to be dependable, responsible, mature. For Jaz there was no such opening. There was no model for his masculinity, no solace in his desertion. So Jaz was lost. So we lost Jaz.

I had a chance to tell you this when you came to Geelong for his funeral in August 1987. I took it too. I dare say that the anger I felt on his behalf contained some of my own; a resentment that my life had been placed on such a serious footing so soon; a pang of failure that I’d been unable to keep what remained of our family whole; a sense of dread that I’d be left to expiate that sense of implication alone. Which is how it played out, me taking myself under ever sterner control as I shook a weakening fist at fate.

But two things: for all the cruelty, it was an accident; for all the hurt, there must be some statute of limitations. That’s another thing my mother imparted – the importance of taking responsibility for your own life. In lots of ways I’ve been fortunate – hell, as a pale, male, able-bodied heterosexual, I won the genetic lottery. My mother came to see your marriage in briskly practical terms, thinks you were probably never truly suited, suspects that you wed to gratify your respective families, is grateful it led to a son and a granddaughter whom she loves. We call you ‘the sperm donor’. So if you left a hole in my life, it became like the hole in a Henry Moore sculpture – comprehensible, intrinsic and not to be filled.

All of which leaves me to wonder: how is it for you now? How is it to be a man at the end of his life, looking back, on not one but two lost sons? For I am as lost to you as Jaz – in every respect other than genetic composition, we’re strangers to one another, and that’s been the case so long it has become a natural state. It’s because of that detachment, in fact, that I can deliver this eulogy. I sense your loss. I sense that weight. I know how our flaws beset us, how our choices can cascade, how long we’ll stave off something we mean to repair, because circumstances are too difficult or shame is too great. If someone told me of a man dying of a dread disease in his early eighties, having been estranged from his sons since his late twenties, I would sorrow for him, even had he failed them every step of the way – it is, objectively, a melancholy fate. There must be a hole in your life too: darker perhaps, more jagged. And given it is a hole of your making, that must be hard to live with, and to die. If you regret the choices you’ve made, that’s sad. If you don’t, that’s sadder still.

I look at that photo of me now, just after my sixth birthday, wearing my collar, tie and shy smile, waiting for you to return from America, waiting to be filled with paternal love, waiting perhaps for that father of Paul Connolly’s imagination, to build the roof and fix the leaks, to cradle the newborn and change the tyre – that father who never came. I see that boy, and I know it’s going to be hard for him. But I also know that, with the benefit of time, he’s going to be okay – partly, I have to say, because he’ll find, in your life, an example of what not to do. He’ll make lots of mistakes, but they’ll mostly be his own. He’ll experience many sad days, but end up thankful for what he has. And eventually he’ll stand before an audience, with serenity in his mind and peace in his heart, and declare that you’re forgiven.

I don't know anything about my dad. Never met him. Don't know his name. I often pondered whether I would be better off knowing him. This piece went a long way towards resolving that question for me. Thank you Gideon.

Powerful and deeply personal. Brave piece. Thanks for sharing.