This Cricketing Life

GH on a joyful new book

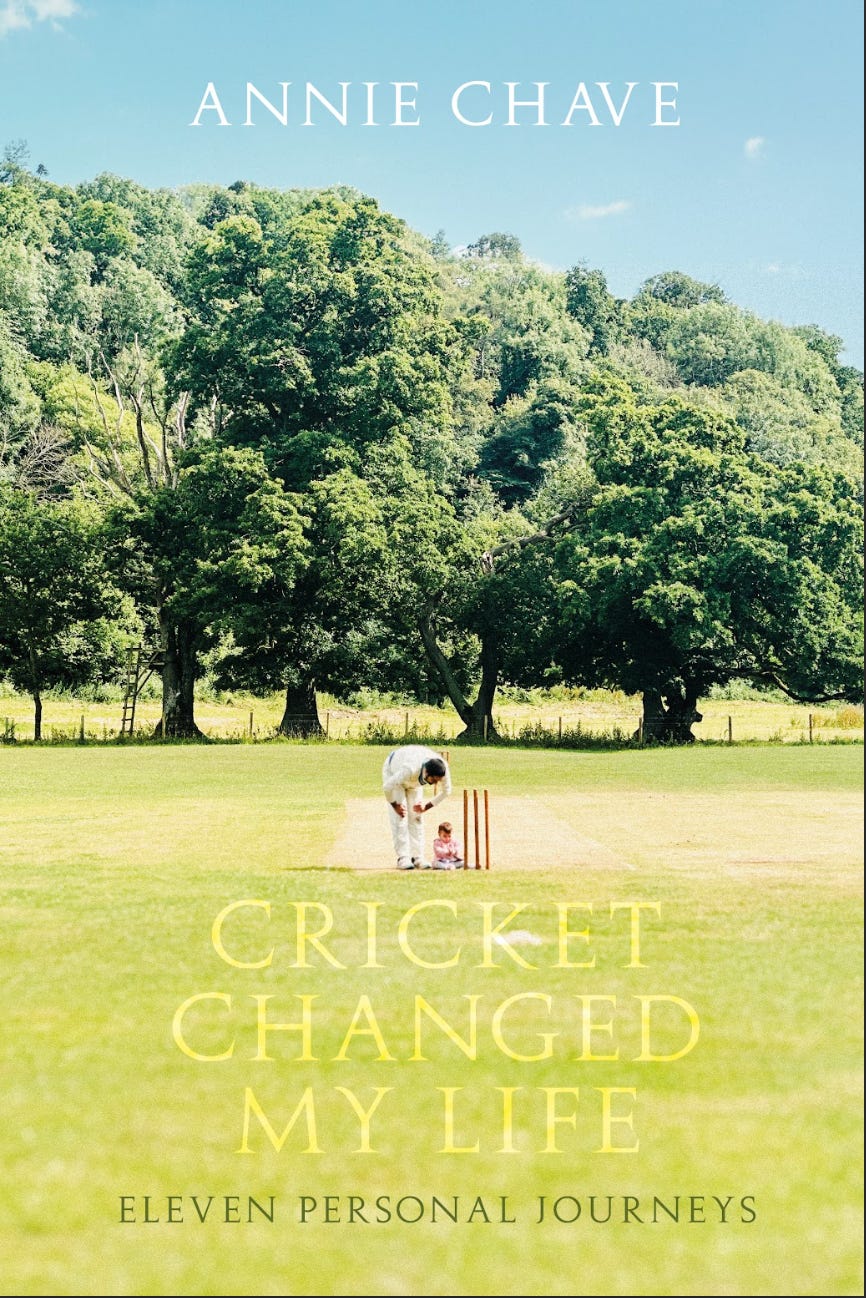

I chanced on this photograph the other night while tip-toeing through images in the collection of the State Library of NSW. It was taken in the Ladies Stand during the Sydney Test of 1961. It contains, I think, much to see. This distaff Thomas Miles is similarly serious. With what looks like a propelling pencil in her right hand and an eraser in her left, she is resting her scorebook on its customised valise, oblivious to the spectator on one side is reading a book, the spectator on the other chatting to a neighbour and the visitor in the aisle draining a Coca-Cola. It occurred to me that of all cricket’s many roles, scoring may be the closest to pure service - you cannot, after all, score yourself. And it detained me because I was at the time reading Annie Chave’s delightful new book Cricket Changed My Life.

Annie began scoring for her father’s Exeter University staff team, the Erratics, aged nine. She once scored a game involving her father, husbands, brothers and son. She has played also, and now edits the quarterly County Cricket Matters. But that passage to cricket via scoring provides a flavour of its slow-dawning pleasures - nobody comes to football or golf through scoring, do they? Scoring cricket is careful, painstaking work, to be undertaken with utmost fidelity - the undergirding of every match, the basis of the statistics that fascinate so many of its votaries. And have you ever seen the looks of quiet panic among those involved when it’s realised, at the end of a tight match, that…the books….don’t….add up? The way cricket is scored, then, tells you a lot about it.

Cricket Changed My Life aims to draw you in similarly. It is composed of eleven profile interviews with ‘cricket people’ of all different kinds. Annie has assembled it with a scorer’s quiet, self-effacing dedication. She is an attentive listener to stories as diverse as those of Waleed Khan, a survivor of the 2014 Peshawar school massacre sustained through his recovery by thoughts of renewing his cricket, and Callum Flynn, the bone cancer survivor who now leads England’s physical disability team. There are three male international cricketers, David Lloyd, Roland Butcher and Fred Rumsey, and two female, Enid Bakewell and Sue Redfern, even if it is not their eminence that distinguishes them so much as their stories.

Annie identifies with them readily. ‘If I nod any harder my head may topple, I think,’ she writes when Redfern begins talking about finding her way in the game at a local club, in all the rituals of preparation and organisation. ‘I’d go further. I’d say these are the essential times, when the game enters your being so completely that you won’t ever lose it.’ It is also a curious book for a reader, because, as the subjects share their tales, you sense you’d like them too - that’s another of cricket’s magical properties, that a love of it so quickly binds otherwise complete strangers. Not that everyone here is a stranger to Cricket Et Al - there are pre-existing friends in Bharat Sundaresan and Daniel Norcross. But it does feel that, at some level, you already know them all.

This is Annie’s first book, and because I hope she writes others I trust she will not take a couple of comments amiss. She should beware the tyranny of direct quotation, which reduces the journalist to stenographer, and could afford to be a more ambitious interviewer. Lots of things inspire passion. It’s perfectly possible to conceive of Model Railways Changed My Life or How I Fell In Love with the Fibonacci Sequence. How is the affinity for cricket so distinctive? I love Bumble, not least for his allegiance to the Mighty Fall, but couldn’t help feel that the interview, for all its well-honed anecdotes, felt a little routine. Butcher hews pretty closely to his book, and Rumsey could clearly talk for England too.

Which is a pity because when Annie does ask the burning question, she gets fantastic answers. A particular highlight of her book is a chapter on Wissal Al-Jaber and Maram Al-Khodir, two refugee girls who have benefited by the amazing Alsama Project, an NGO in wartorn Syria founded by Richard Verity and Meike Zeirvogel using cricket as the foundation of its educational mission. ‘I knew how much I loved cricket,’ Verity explains.

But I hadn’t quite realised what a mystical, powerful sport it can be. It teaches success and failure, which is incredibly important. To start with the kids can’t take it, and they get angry when they fail. They’ve had too much pain in their lives. They haven’t realised that success and failure are both constrained, and that failure is also part of the enjoyment. The success will come in its own time. Also, critically, cricket teaches leadership for girls. You can’t give leadership roles in the classroom easily, but on the cricket pitch, it’s straightforward. Just make them captain or make them coach.

When Annie asks Maram about the game’s appeal, her joy brings a tear to the eye.

Oh this is an amazing question. So you are asking why cricket? Why not another sport? Well, first of all, cricket includes boys and girls together. This is really important for us because, as you know, people in the Middle East believe in males more than females. If you can play something like this or anything that embodies these two genders together, you will love it. So this is first reason. The second? It doesn’t just rely on strength but on mental, and this is amazing for the girls. For us, for example, we don’t have lots of strength but we have sometimes won against the boys because we use our mentals and they use their strength, so it’s really amazing…

My family were really closed. They just wanted me to sit at home, wear long clothes, not to chat with boys. Don’t do this. Don’t do that. I felt like a butterfly that couldn’t fly. But then when I entered the playground, I didn’t feel like this. I could move between flowers and felt free to play, to love, to dance, to sing, to do whatever. During the game I’m singing, and I’m dancing, because I find it is a great chance to express myself, and that’s what Alsama cricket is giving me.

There is a lot to this. Cricket is a big, encompassing game. It allows a mind free play. It is concerted and loose. It is beautiful and ugly. It is acutely personal and profoundly communal. It has intense bursts and casual longueurs. All these enrich its metaphorical qualities - cricket feels like life in a way other sports, I think, do not, quite. Its duration, further, conduces to the savouring of sights, and smells, and sensations, and sounds. The last of these comes up, for instance, in another deeply moving interview with the broadcaster Georgie Heath, struck down in her late teens by a desperate eating disorder, and sustained through her nightmarish existence in a dementia ward by the soothing rhythms of commentary on the 2017-18 Ashes.

I’m in a hospital where you’re awake through the night and all you can hear is dementia patients yelling this, that and the other. And I literally spent the entire time with the Ashes in my ears, basically to try and keep myself sane….and then when it finished I’d rewind it to the beginning and listen to the whole session again, because it was the only thing that kept me going.

Not all the interviews were done in person, and at times it shows. Annie has a nice touch when she’s present, as when she observes Rumsey’s way of pervading his family home: ‘It’s a table that Fred commands. He’s a man who requires space.’ Less necessary is a tic of signposting her questioning, as in the same chapter: ‘I’m conscious, though, that, before we discuss the PCA, I need to hear more about his early life, so I steer the conversation to post-school and early employment’; ‘Keen to stick to cricket, I ask if the travel involved going to cricket grounds.’

When the formula works, however, the result is deliriously good. The chat with the great Enid Bakewell is full of absolute gold - she’s clearly a woman after Annie’s heart, taking eight for 53 when she was six months’ pregnant. She touches on the importance of imitation in cricket: ‘I modelled my left-arm spin bowling on Tony Lock. I even had the same number of steps in my run up.’ She tells wonderful stories of her fitness regime in the village of Annesley Woodhouse: ‘I would read Lorna [her daughter] a story and then put on my training gear and go outside. On the pavement i would wait until a car approached and I would attempt to race it past two lights. Then I would go back and repeat the process.’ She gives her otherwise nondescript husband a kindly send off: ‘He died aged eighty-six which was the same as his highest score in cricket. I found him on the floor dead, and so I can’t sleep in that room. Instead I sleep in the single bedroom next to the toilet.’

‘If bad things happen, I will run away to cricket,’ concludes Dan Norcross. ‘And when good happens, it makes me love cricket even more.’ In such moments, Cricket Changed My Life, like a good scorebook, adds up perfectly.

You can order Cricket Changed My Life here.

"cricket feels like life in a way other sports, I think, do not, quite." Absolutely Gideon - as I say to my wife when she moans about yet another day watching Text cricket - "it's life in miniature, how can you not love it?"

County Cricket Matters, the no-frills, inexpensive, quarterly magazine that Annie launched and edits, is highly recommended. CCM is a strong advocate of country cricket, produced for the love of the game, by genuine supporters.