Why You Must See the Stick Shed

GH on Australia's greatest building

Last August, I paid a visit to Murtoa in the Wimmera, and extolled its many virtues here, while promising further on its most famous building which I’m convinced is Australia’s greatest - or, at least, the building most authentically Australian. If you’re here for the Cricket only, pass by as you please; but if you’re in the mood for quite a lot of Et Al, here is an overdue digest of reasons to visit the Murtoa Stick Shed.

ITS NAME: Let’s start with something simple: its deliriously laconic nickname. ‘Stick Shed’ appears to be a relatively recent construction. Officially it was the ‘Emergency Grain Storage’ or ‘Number 1 Grain Store’. Unofficially locals referred to it and a larger companion as ‘the Bins’. ‘Stick Shed’ came into vogue just as the Grain Elevators Board, its owner, was discontinuing its active use, well before the building’s inclusion on the National Heritage List ten years ago. To refer to a 560 unmilled hardwood poles as ‘sticks’ and a structure 280m by 60m standing 20m high as a ‘shed’ exhibits the same Australian capacity for casual minimisation as referring to ‘the Ditch’ (the Tasman) and ‘the Coathanger’ (Sydney Harbour Bridge); Melburnians have a modern counterpart in ‘Jeff’s Shed’ (Melbourne Convention and Exhibition Centre).

ITS SETTING: The Stick Shed rises, Uluru-like, from the flat, windy plains of the Wimmera which compose a tenth of Victoria immediately east of the South Australian border, and still make the largest regional contribution to the state’s wheat crop of about three million tonnes. Murtoa, 305km north-west of Melbourne, is home to fewer than a thousand people. Even the local Progress Association calls it ‘quaint’, and the bulk of Australia’s largest corrugated iron building is so incongruous that Erich Von Daniken would probably have chalked it up to aliens.

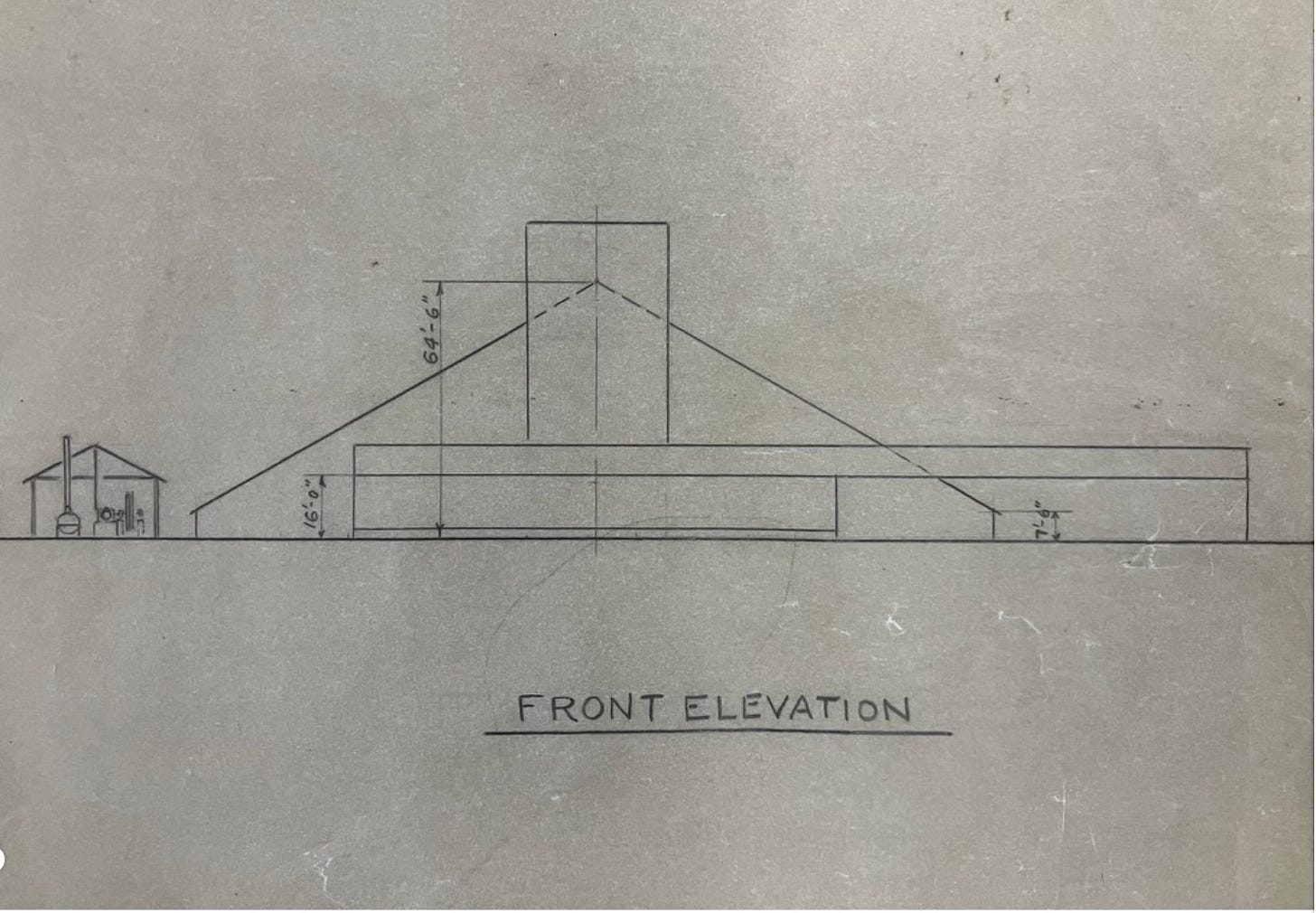

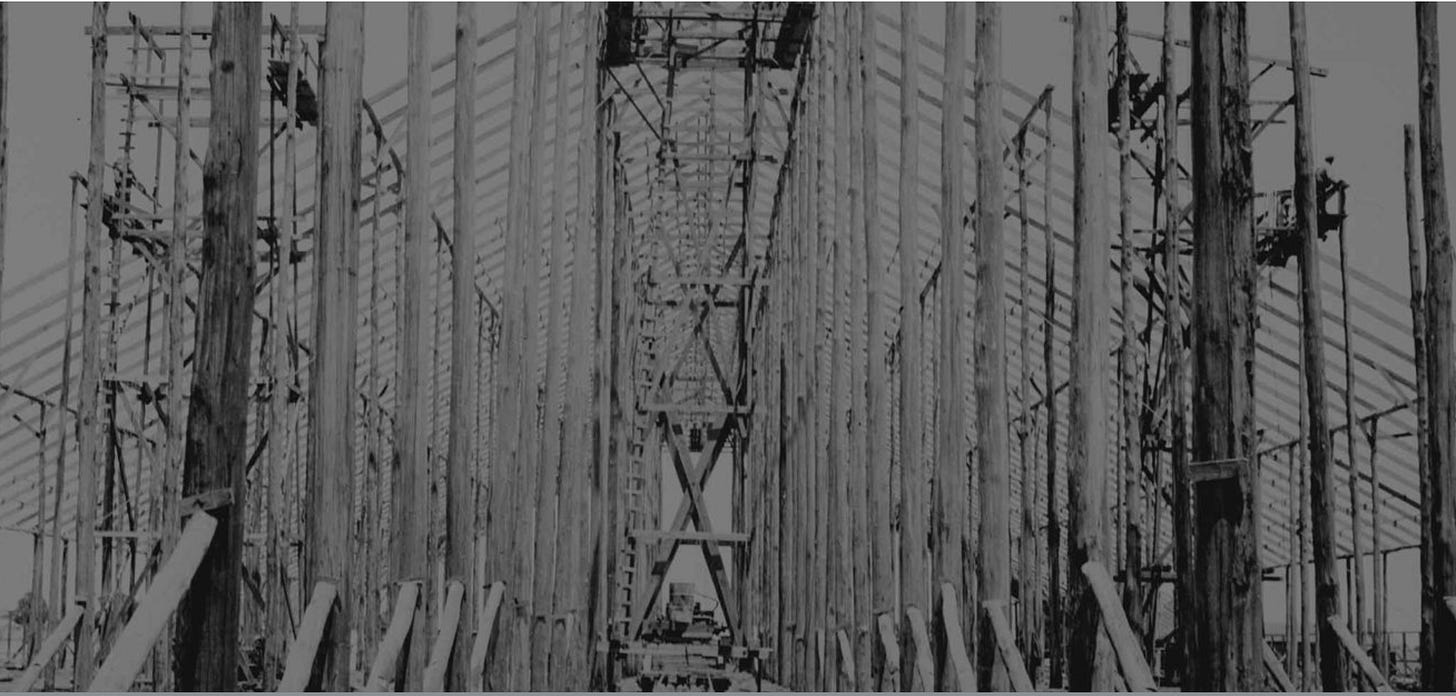

ITS BEAUTY: A vernacular cathedral is the nearest metaphor. At one end, the elevator soars like a steeple

The nave inside leads to the altar of the hopper, lit with candle-like pinholes of light from absent nails and screws.

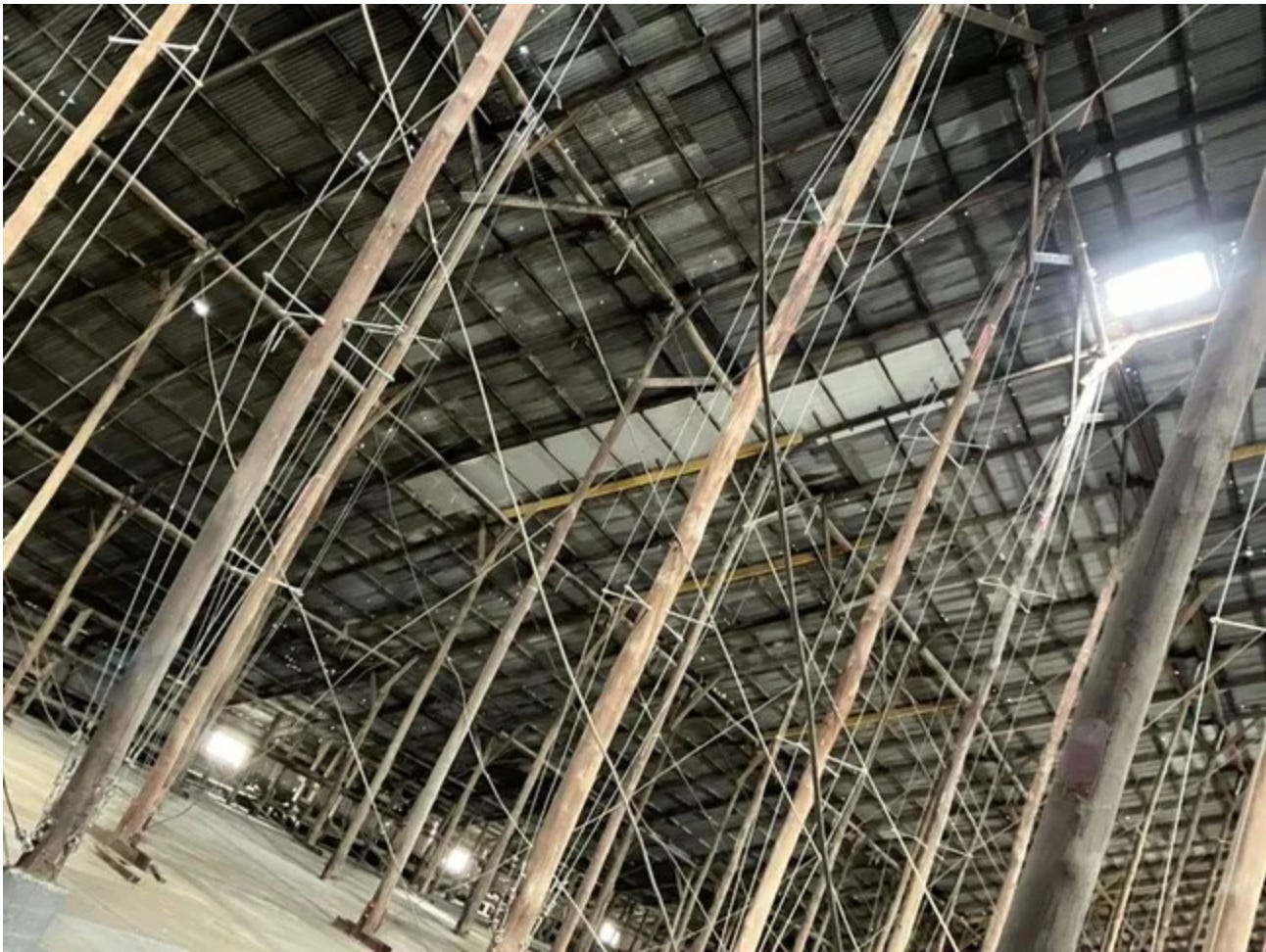

And nothing can quite prepare you for the restrained beauty of the Stick Shed’s vaulting interior, the ghostly receding columns, the shafts of fluctuating illumination from its forty skylights, the immensity of its silences - for it is easy to find yourself the only person there. Bow trusses between the poles savour of a clipper’s rigging. It was still on the two days we visited, but when the winds blow it’s said that you can feel the building move.

Conveyor belts in place might be optical illusions…

…while those in disuse lie coiled like gigantic plants.

Even the cobwebs are artfully draped.

Anyway, you get the picture: more here, by better photographers than me.

ITS PURPOSE: Look closely and you’ll see that the structure is all about its former function. It is positioned perpendicular to the railway between Adelaide and Melbourne; its hip roof is pitched to match the natural twenty-eight degree repose of piled wheat; its existence expresses a long-forgotten commercial argument between bagged and bulk wheat, helping to resolve it comprehensively in the latter’s favour.

Wheat is Australia’s original crop, first grown at Farm Cove in 1788, and massively expanded by the Scullin government’s ‘Grow More Wheat’ campaign, during which Australia’s share of global exports grew to a fifth. When many other Depression-addled governments round the world made the same call, however, the wheat price halved and the handling of surpluses became a national challenge.

Life was different then. A majority of Australians lived outside cities; the economy of Australia was overwhelmingly dependent on primary industry; Australia’s Country Party was at the zenith of its influence, personified by prime ministers Earle Page and Arthur Fadden, and Victorian premiers Albert Dunstan and Jack McDonald. It was a huge deal when, after the deliberations of a wheat industry royal commission filled five volumes, Victoria’s government made the Grain Elevators Board (GEB) responsible for the construction of country grain elevators and a terminal in Geelong, portending the silo system.

Three weeks after the Nazis stormed into Poland, however, the federal government stepped in to establish the Australian Wheat Board - a monopoly price setter and policy maker for the entire national harvest, power reinforced by 1940’s Wheat Stabilisation Act. Relations between the Wheat Board and Grain Elevators Board quickly grew testy. One thorny issue was that, traditionally, Australian millers preferred to receive their wheat in three bushel bags, woven from jute in India.

They were expensive; their supply was often unreliable; they were readily degraded by reuse. Membership of the Wheat Board was dominated by grain handlers to the exclusion of growers, and the sector hastened slowly in any case. But as war closed global shipping lanes, Australia faced a 200 million bushel surplus. The situation was particularly dire in Victoria, with the Grain Elevators Board having managed to finish only forty-eight of 160 planned silos. The responsibility to fix this fell to the GEB’s chairman Harold Glowrey. He was determined to dig in against the bag lobby.

ITS DESIGN: Most notable buildings are associated with a God-like architect. Harold Glowrey is the very opposite. Son of a Swan Hill storekeeper, his formal education ended at age 12, and he worked for the softgoods giant Sargoods before settling on a farm in Ouyen. Rural politics was then in its infancy. Glowrey became assistant secretary of the Country Party’s precursor, the Victorian Farmers Union, then won election to the Legislative Assembly as a candidate of its rival, the Country Progressive Party. The CPP briefly held the balance of power in a tumultuous period: between 1924 and 1929, Victoria had no fewer than seven premiers; using his sway with Labor premier Ned Hogan, Glowrey gained for Ouyen a secondary school and a hospital.

Glowrey was celebrated by contemporaries for his industriousness, despatching as many as 500 letters a week, and his candour, as noted by the Ouyen Mail: ‘Mr. Glowrey's modest and unassuming manner, his intimate conversational way of speaking, and his thorough knowledge of Mallee conditions with his sincere sympathy with those of his constituents that are in need carry him straight to the "Hearts” of his audiences.’ Even after losing his seat when he opposed the merger of the Country and Progressive Country Parties, he enjoyed undiminished esteem: Hogan’s close friend John Wren let Glowrey a handsome property near Tocumwal. His appointment to the chairmanship of the Grain Elevators Board by premier Dunstan in January 1940 was widely applauded.

Glowrey’s originally envisioned bulk storage in concrete, following recent trends in the US and Canada. The Wheat Board was opposed. The bag-wedded majority of Wheat Board members, Glowrey noted, liked their profits: ‘It became evident very early…that a large section of the Australian Wheat Board members, particularly those with wheat handling interests, desired to see as much as possible of the wheat in question being handled in bags.’ Concrete and steel, moreover, might prove hard to get in wartime. The minutes of the Grain Elevators Board record a meeting of the directors at Chancery House, 485 Bourke Street, at 2pm on 16 July 1941. Glowrey had called in Ernest Watts, at the time Victoria’s leading builder and contractor, to discuss the feasibility of completing a concrete bunker before the harvest came in early the following year. Watts said, basically, no way:

He advised the Board that he had very grave doubts as to the possibility of the work in question being carried out in the time required. He stated that an enormous amount of formwork would be necessary, also that materials may be difficult to procure, and he feared there was insufficient time to carry out the work. He stated that he also doubted the possibility of securing an adequate supply of the right type of labour.

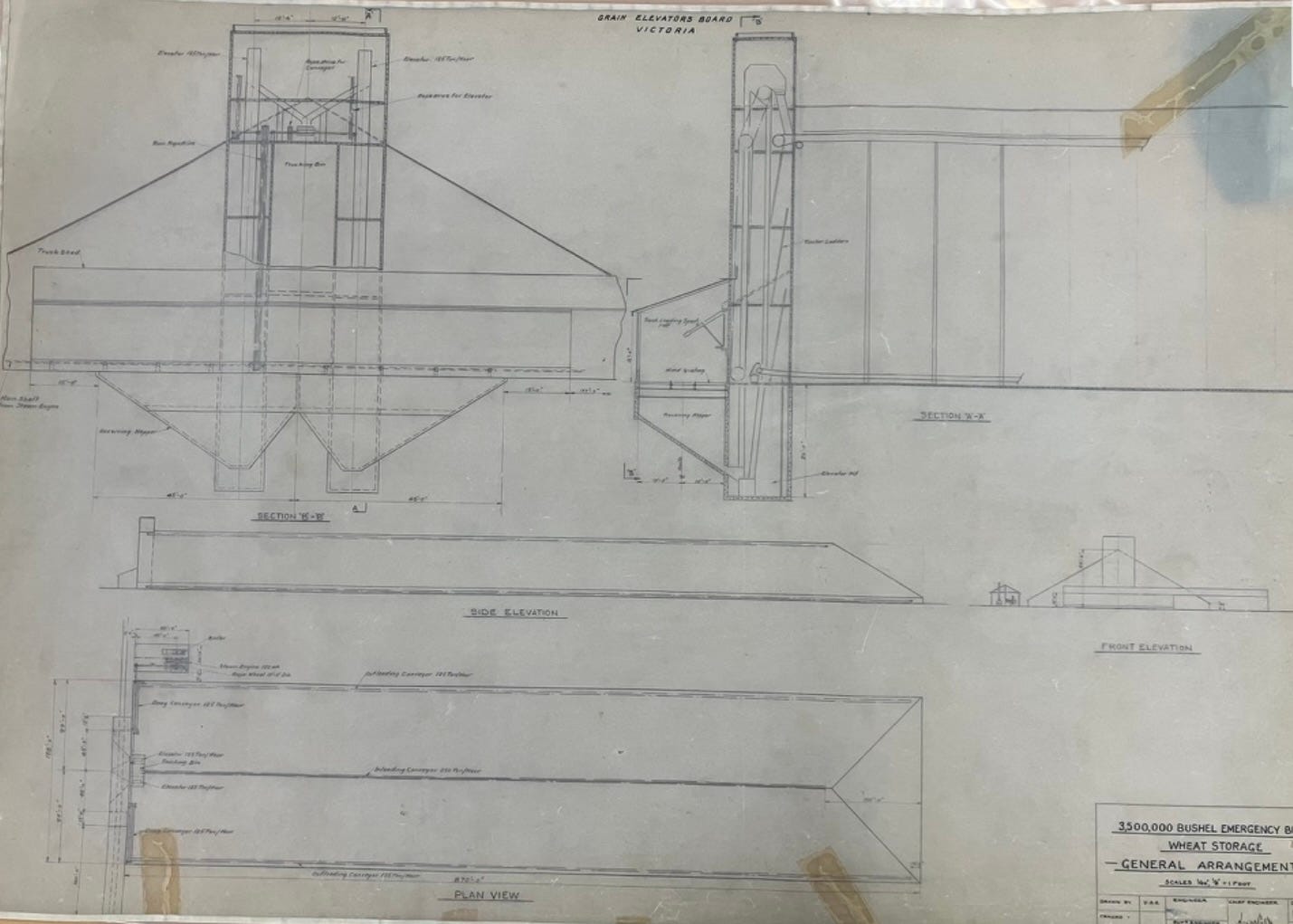

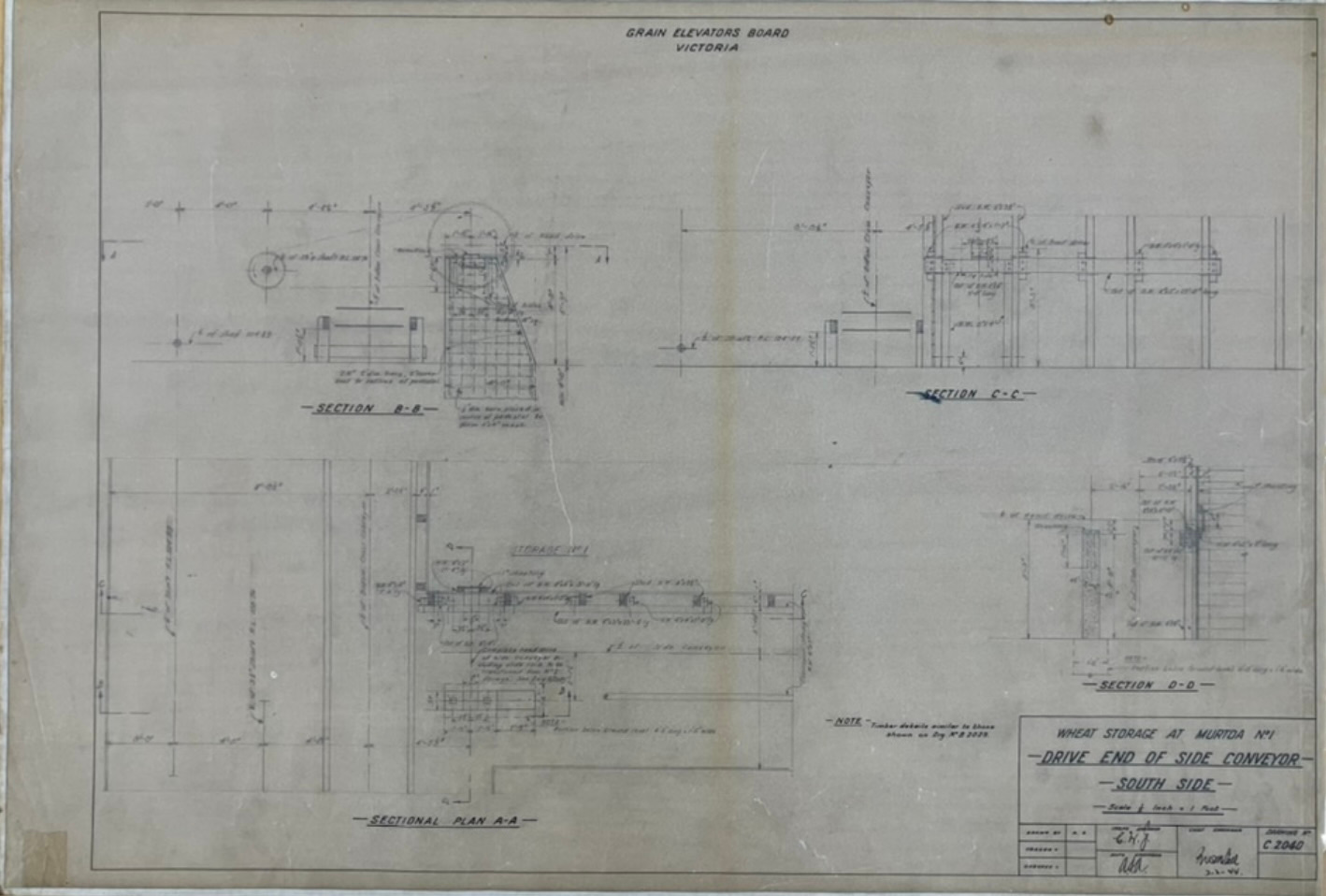

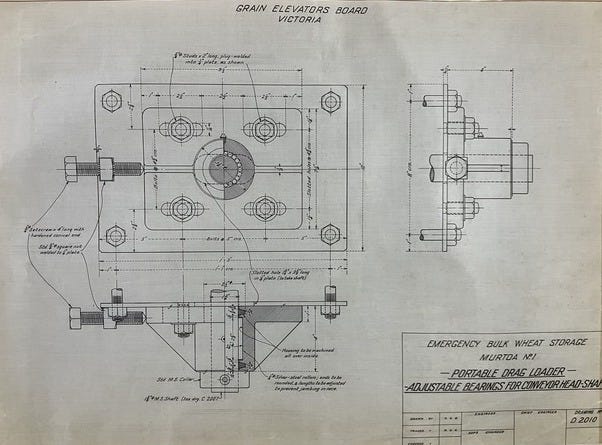

So Glowrey and his chief engineer R. W. McCall began exploring a ‘timber and sheet iron’ construction, upscaling a kind they had seen in Western Australia. The work of McCall’s draughtsmen deserves an essay in itself, in that everything was handdrawn, all the mathematics manually figured, and every individual component designed and machined. Such a building was without precedent in scale and scope; nothing could be bought ‘from the shelf’. The relevant files at Victoria’s Public Record Office range from the large and simple….

…to the intricate and precise.

Remember that this took weeks, not years or even months. There was a war on. GEB minutes record McCall having to replace several engineering staff when they enlisted, borrowing and seconding them from elsewhere. Urgency was added by excellent growing conditions. A record harvest loomed. Where was all that wheat to go? The Wheat Board was prevaricating. As time ticked down, Glowrey performed a classic end run, travelling to Grafton in order to direct his petitions to the minister for commerce, Earle Page. It paid off. The Wheat Board’s minutes for 21-22 August 1941 record its grumpy acknowledgement that Page ‘desired the accommodation be provided and that arrangements should be worked out’, with costs to be split between Victoria and the Commonwealth.

ITS CONSTRUCTION: In an age where government takes three steps back for every two taken forward, the rapidity of the Stick Shed’s rise beggars belief. Within ten days the Grain Elevators Board had selected and acquired a five-acre site in Murtoa, for its convenient relation to the relevant rail line, and opened its first five tenders.

The council agreed to grade the land and Victoria’s railways department to build a new siding, while a locomotive boiler was acquired to provide power for the elevator and conveyors. The scarcest component proved to be timber: Victoria’s hardwood reserves had been almost destroyed in 1939’s Black Friday bushfires. Finding the builder, by comparison, was easy: when Bendigo contractors Green Bros submitted the lowest tender, £13,285 3s 1d, the minister approved their appointment on 18 September 1941. The work commenced a week later with the digging of the footings [below] - a full seven weeks before the contract was formally signed, a man’s word then being his bond.

The man in this question was thirty-three-year-old Herbert Edward Green - a remarkable self-taught builder. One of six children to a Methodist family farming near Woodvale, he received no more than an eighth-grade state school education at Sydney Flat before starting work as a timbercutter. He and his brothers Rob and Ray then formed a construction company specialising in bridges, starting in Swan Hill in 1933 [below].

Green Bros [Bert in hat with his workers below in front of their joinery shed] would later move into civic buildings, including the Bendigo Hospital, Art Gallery and Swimming Pool, and above all homes, building as many as half a dozen a week after the war. But he assuredly reached his zenith with this shed.

What manner of man was Green? He played cricket for Woodvale. He was a mason in Bendigo. He erected the Epsom Methodist Church. Then, when it burned down, he erected it again. Brother Rob would spend most of the war as a prisoner in Changi; Bert, in a reserved occupation, was now running the business more or less on his own. If it daunted him, he would not have shown it. He was not silent, but not talkative. ‘A gentleman,’ says his daughter Shirley [in his arms below, with mother Jess and brother Neville].

So little did Green discuss his work at home that, while he would celebrate the completion of a bridge by bringing home a tin of chocolates, he never in his children’s hearing mentioned his giant assignment in Murtoa. Shirley and Neville were unaware of the Stick Shed until last year, when a friend visited, and realised the family connection. They now believe the figure in the foreground of this photograph, nonchalant as a camper about to erect a tent, to be their father.

Part of the legend of the shed is that Green’s workforce, thanks to wartime labour shortages, consisted of ‘kids and cripples’ - those too young to enlist or otherwise medically excused service. This is difficult to confirm in the absence of detailed personnel records, but we do know, from weekly updates in the Dunmunkle Standard, that local enlistments were extensive.

Grain Elevators Board minutes, meanwhile, feature reports such as this.

Workers had the bare minimum of mechanical aid and little direct oversight from head office - precisely one telephone, with a ‘loud sounding bell’ in a temporary office. But despite or maybe indirectly because of this, the erection moved swiftly from here…..

…to here….

…to here.

A concrete floor was laid, four inches deep, on top of a layer of Sisalkraft - a bituminous laminated paper stipulated by the Wheat Board. The giant conveyors were installed and work commenced on the towering elevator. The scorching summer sun and unabating Wimmera winds made the roof - 150 tonnes of corrugated iron in lengths of five feet and ten feet - an especially arduous phase of construction. But, with farms burdened by nearly three million bushels of wheat, the need was growing desperate. When Glowrey accompanied the member of Kara Kara-Borung, F. A. Cameron MLA, to the site on 9 January, they were clearly conscious of the clamour from growers, pleading via the Horsham Times.

They kept their promise by erecting a temporary elevator: when the first bulk wheat arrived on 22 January from Maurice Delahunty, a twenty-five-year-old farmer from Murtoa’s ‘Roscrea’ estate, it was poured through a hole in the roof. And soon as the permanent elevator was completed three weeks later, ‘Number 1 Grain Store’ worked exactly as intended: its 3.38 million bushels of wheat lay undisturbed for two years through a pitiless drought.

Gradually, external pressure eased, the worldwide grain surplus was depleted by famine in Bengal and war in Ukraine, and the trucks began to rumble. By January 1945, the stick shed was empty again, and not a grain had been wasted.

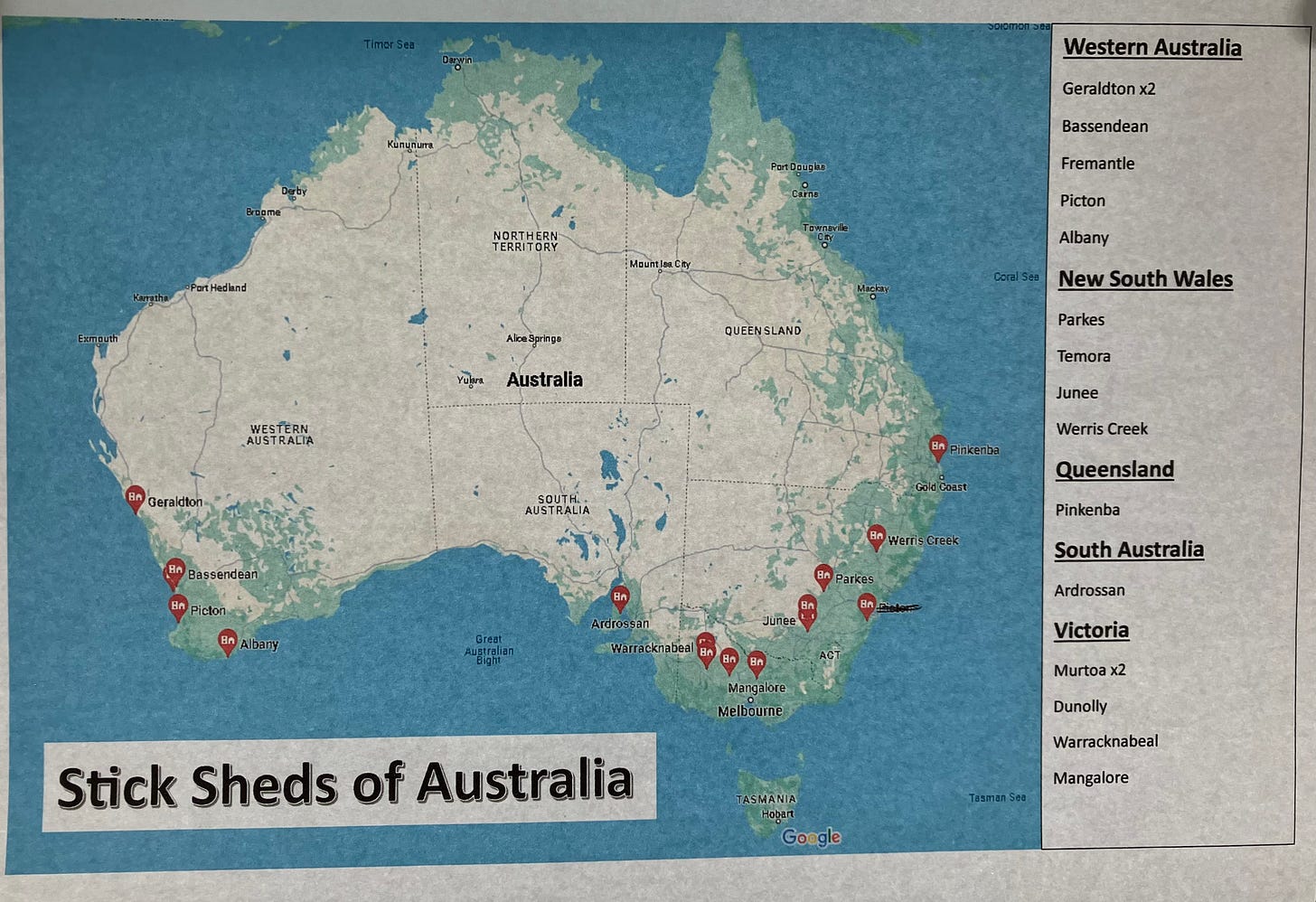

Glowrey’s fellow director S. Lockart [above] told a conference of the Victorian Wool and Wheatgrowers Association that his chairman had been vindicated: the stick shed had ‘proved that wheat could be stored indefinitely with proper care without deteriorating.’ Bulk wheat had begun a steady eclipse of bagged wheat, as Murtoa heralded the stick shed age. For no sooner had the inaugural stick shed received its first wheat, than construction commenced of second larger shed alongside it, this one with a floor of galvanised iron sheets, then a third larger still in Dunolly. It turned out that bulk wheat storage was an idea whose time had come: there would eventually be no fewer than seventeen buildings of the type in five states, the last of them completed in Parkes in 1954.

ITS CONTRIBUTION TO SCIENCE: Yes, really. Stick sheds spread thanks to the conquest of one long-held reservation. In their campaign against Glowrey’s original vision, the grain handling lobby had played up the risk of insect infestation, relying on a 1940 study of the bulkheads in Western Australia by Francis Ratcliffe of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research’s division of Economic Entomology. But when Ratcliffe’s colleague Frank Wilson, a young English-born entomologist, was sent to Murtoa to study inland grain storage, he made an important observation. In the lower-humidity Wimmera, weevils were found only in the surface level of the grain: the heat of the heap prevented the insects penetrating more deeply.

Because it was impractical to strip away the mound’s upper layer, this had no immediate application. But further research, following the work of British scientists, brought the discovery that the weevils could be essentially cooked by roughly distributing non-poisonous carbon bisulphide or ethylene dichloride over the stockpile’s surface. Bulk wheat was not only cheaper than bagged; it could be rendered more pest-resistant. When Wilson’s work was reported in January 1945, The Herald revelled in the whackiness of it all: ‘Weevils attacking wheat in bulk stores in Victoria have been sentencing themselves to a form of death as weird as those invented by the writers of the scientific pulps — they dehydrate themselves and die, surrounded by food, from lack of moisture in their bodies.’ Wilson’s four papers, including ‘Surface fumigation of insect infestations in bulk-wheat depots’, became some of the CSIR’s most influential and cited reports. In Australia’s official history of World War II, the chemist David Mellor describes Wilson’s inert material dust experiment at Murtoa as ‘the first of its kind’ and ‘a notable advance in the bulk storage of wheat’, heralding the CSIRO’s pioneering development of insecticides in the 1950s and 1960s.

ITS COMMUNITY: The people of Murtoa readily habituated the Number 1 and Number 2 Grain Stores, which they also knew as Marmalake. As a sight, such facilities were no longer so unusual: the storage at Dunolly, with a capacity of six million bushels, was nearly twice the size of Number 1. At peak season, two shifts operated, 8am to 4pm and 4pm to 2am, knockers, rakers, shunters, drivers and other members of the work gang alternating weekly, with a ten-minute smoko every two hours. In busy summer, ranks of workers were swelled by itinerants and part-timers; in quieter winter, local footballers used the wheat mound as an ersatz sandhill to run up. As a workplace, it had a roughhewn occupational health and safety regime recalled in a memoir by Frank Lehmann, a local teacher who worked at the grain store part-time in the 1960s:

When the wheat spewed out the dust was intense. This was one of the occupational hazards of the job. I once asked [manager] Dick Dalton if the men should not be getting some recompense in the form of ‘dust money’. It was pretty much accepted practice to cough up ‘pancakes’ after a few hours working there. The answer I received was negative. Wheat dust was not considered to be dangerous to the respiratory system like coal or metal ore dust. The reason was that, being vegetable matter, it would eventually dissolve away leaving no ill effects.

It was not the workers who eventually told against bulk storage. By the 1970s, international buyers were growing fussier about grain hygiene, while growers were experimenting with differentiating grains in search of premium prices. Vast grain mountains began looking anachronistic. In 1975, the GEB demolished Number 2 Grain Store; they spared Number 1 probably only because its concrete floor was less salvageable than Number 2’s galvanised iron floor. But just as they came back to see to Number 1 after flattening Dunolly in 1987, it dawned on some onlookers what was in their midst.

ITS SURVIVAL: On 1 October 2014, the Stick Shed was inscribed in Australia’s National Heritage List as entry number 101. It was the culmination of a quarter of a century’s advocacy, led by a small but determined group of locals. They were afforded their opportunity when, in the nick of time in December 1989, Victoria’s Historic Buildings Council stymied the GEB’s demolition plans; the Stick Shed was classified by the National Trust a year later. Its champions in Murtoa, however, were decidedly unpopular, accused of standing in the way of progress, of defending an ‘eyesore’.

‘Hostility in Murtoa was exposed often and verbal abuse frequent,’ recalls Leigh Hammerton in his comprehensive chronicle of the building’s preservation Shedding Light (2019). ‘It went further, with any local supporters being harassed publicly in the local hotels and in their businesses or employment. I experienced it many times, and it took some toll on my perspective. I often felt ostracised, threatened and decidedly in the minority.’ But then the Stick Shed, having outlived not only its promotor Glowrey and builder Green, outlasted its owner: when the Grain Elevators Board was sold to Grain Corp in January 1995, the building was deposited in the somewhat bemused hands of the Victorian Government Property Group, buying valuable time for locals to rally. Various schemes have been mooted for its use - including, bizarrely, as a location for aquaculture. Although Grain Corp still use the elevator at harvest time, the Stick Shed’s main job now is to be visited, which it is about 20,000 times a year. Its largely volunteer staff are zealous and patriotic, and there is reason to be warily confident of its future. Leigh’s sixteen-stanza poem ‘Stick Shed Saga’ concludes triumphally:

I thank those souls from years ago who took it to their hearts.

Some saw a future for this Shed, with those from different parts.

The outcome was, and is superb, the drops of blood we bled

Were all worthwhile, because we saved Murtoa’s Mighty Stick Shed.

ITS SHEDNESS: The shed might be regarded as the characteristic Australian building form, a place of furious industry….

…and soothing repose.

‘Sheds are an integral part of Australian life,’ says Mark Thomson in Blokes and Sheds. ‘No other nation values them as we do. Despite this, our sheds, modest from the outside yet glorious on the inside, have never really been recorded or their many purposes explained.’ The Murtoa Stick Shed, then, is the apotheosis of a structure we uniquely value: practical, beautiful, and enduring; not just a salvation for its users, but a cradle of innovation and a rallying point for community. So, sure, see Naples and die. But see Murtoa and wonder.

Sensational. I did not expect the to-and-fro of the Grain Elevators Board to be this engrossing. The highlight for me was hearing about the Dunmunkle Standard. I have long fancied a free-form roam around regional Vic looking at footy grounds, scoreboards and grandstands but this is right in my wheelhouse.

Very impressive Gideon and I am particularly taken by Bert Green. As an old Bendigoian, I came onto the playing field via the Bendigo Hospital, was always in awe of the Art Gallery (and it’s gone from strength to strength) and learned to swim in the freezing waters of the pool as a ten y o. Incidentally that same pool, after becoming not much more than a swamp due to serious neglect for decades by authorities who should have known better, only last week completed its transformation to a calming lagoon, half the size of the next door Queen Elizabeth Oval, the QEO (which my dear mum always referred to as the “curio”). A fitting extension of Bert’s early vision.